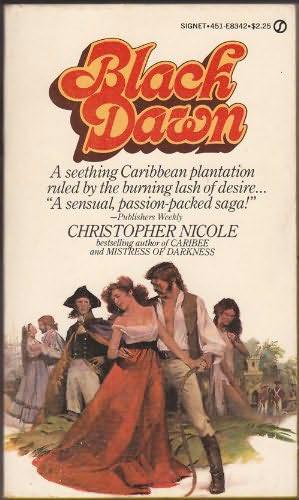

HF - 04 - Black Dawn

This is the fourth novel in Christopher Nicole's history of the West Indies, from the founding of the first colony to Emancipation in 1834. It includes CARIBEE, THE DEVIL'S OWN and MISTRESS OF DARKNESS.

Black Dawn

Christopher Nicole

CORGI

BOOKS

A

DIVISION OF TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS LTD

BLACK DAWN

A CORGI BOOK 0

552 10918

5

Originally published in Great Britain by Cassell & Co. Ltd.

Printing history

Casselt edition published 1977 Corgi edition published 1978

Copyright Christopher Nicole 1977.

Corgi Books

are

published by Transworld Publishers Ltd., Century House, 61-63 Uxbridge Road, Ealing, London, W5 5SA

Contents

i | Prelude to Disaster | 9 |

2 | The Opportunity | 15 |

3 | The Coward | 42 |

4 | The Inheritance | 68 |

5 | The Planter | 93 |

6 | The Betrothed | 119 |

7 | The Fugitive | 145 |

8 | The Brother | 164 |

9 | The Castaway | 193 |

10 | The | 216 |

11 | The Soldier | 245 |

12 | The Emperor | 264 |

13 | The Crisis | 284 |

14 | The Claimant | 303 |

15 | The Witness | 328 |

16 | The Trial | 347 |

17 | The Incendiary | 370 |

18 | The Day of Retribution | 404 |

Prelude to Disaster

A roll of drums reverberated across the still of the afternoon. It rumbled up the hillside behind Charleston, climbing the single great mountain that dominates the island of Nevis; it seeped across the calm Caribbean Sea, perhaps heard in neighbouring St Kitts; it shrouded the weatherbeaten houses of Charleston itself, sending a rotting wooden shutter banging, seeming to accentuate the peeling paint, the crumbling shingles of the sloping roofs. If the Americans' successful war for their independence had left all of the West Indies in straitened circumstances, nowhere was poverty quite so evident as in the smaller islands, and nowhere in the smaller islands so much as in tiny Nevis.

And the drum roll stirred the crowd. It was a recent crowd, gathered by the waterfront. Its members had come here, panting, swinging bottles of rum, in haste from inside the courthouse, if privileged; from the street outside, if black and therefore unprivileged. They had been hot, and sweaty, and excited. In the past hour their enthusiasm had somewhat cooled along with their skins. But now it was awakened again, by the rolling of the drums.

It was a decrepit crowd, in keeping with its decrepit surroundings. The white people, men and women, who formed the first ranks, were sallow and emaciated; their linen was soiled, their hair lank. They shaded their heads beneath wide and tattered straw hats, indulged in no frills such as stockings or cravats; the setting sun silhouetted the legs of their women through the thin muslin gowns and chemises which were all

any of them wore.

The black people formed a much vaster gathering, behind and to either side of the whites, and revealed a proportionate poverty; not one possessed more than a single garment, a pair of drawers for the men, a shift for the women, and none wore shoes. Their bodies were half-starved, bones seeming more prominent than muscles, faces hardly more than skulls. And like the whites they gazed, in almost silent wonder, at the gallows standing immediately before the worm-eaten wooden dock which thrust its ancient timbers into the pale green of the sea. They could not believe they were witnessing this scene. They knew, indeed, that they would

not

be witnessing this scene, but for the line of red-coated marines which stood between the crowd and the dock, but for the frigate which rode to anchor beyond, her guns trained on the town. And but, too, for the sloop which also lay at anchor, close to the frigate.

'Hiltons,' muttered one of the white men.

'Nigger lovers,' said a woman.

'Scum,' said another.

'Traitors,' shouted another.

Heads turned to look along the street at the balcony of Government House, only slightly less decrepit than the buildings which surrounded it, above which the Union Jack floated lazily in the gentle breeze. But the crowd's enmity was directed against the three men who had appeared on the balcony. It was composed of jealousy, certainly; each of the three was well dressed, if scarcely more elegantly than anyone else, with open coats, and an absence of vests or cravats—but there was no emaciation in

their

faces. And it was composed of fear, equally certainly; Hugh Elliott was Governor of all the Leewards, and he had declared a state of emergency this day, which gave him power of life and death over everyone present. But even the Governor had no such power, no such ability to reach out and seize what he wanted, and tear it down or build it up, as the two men who stood, one on each side of him. Obviously they were related; they possessed the high forehead, the thrusting chin, the grey eyes and the surprisingly small, exquisitely shaped nose which dominated the big fea

tures surrounding it. Only in si

ze were they clearly differentiated: Robert Hilton was of average height and heavily built in shoulder and thigh— he was some years the elder. His cousin Matthew was tall and slim. But their appearances counted for nothing. It was the name whic

h mattered, the history which ill

uminated the Hilton family like a beacon, the wealth which surrounded it like a suit of armour. And the power created by that wealth, a power which could bring about a scene such as this.

For the drum roll was again increasing its tempo, and from the courthouse there now marched another squad of marines, muskets at the slope, confident in the protection afforded them by their fellows. In their midst walked two men. The priest read from his Bible, finger tracing the lines; his voice was low, intended to be heard only by his companion. But James Hodge was not listening. He turned his head from side to side, seeking his compatriots, seeking his enemies, looking up at the balcony as he passed beneath. Perhaps he too would have shaken his fist had his hands been free.

A sigh rose from the watching whites, while the very last sound ceased from the Negroes. One or two of the older men and women amongst them had actually seen a white man hang; but he had been a pirate. James Hodge was a planter, and his crime was neither piracy nor treason.

The procession reached the foot of the scaffold, and halted. The drum roll faded, and the afternoon was for a moment utterly quiet. Hodge's shoes could be heard on the wooden steps as he climbed them, assisted by the priest. And now the hangman and the bailiff also appeared on the platform; hitherto they had sheltered behind the soldiers.

The boards creaked as Hodge turned to face the crowd. Slowly he filled his lungs with air. 'Scum,' he bawled, his face red. 'You stand there, while I hang. But when I drop, you all drop with me. You . . . '

'No speechifying, Mr Hodge,' said the bailiff, and held his arm.

'Scum,' Hodge bawled again.

'Filthy wretches. Lousy . . . ‘

The words gagged in his throat as the hangman dropped the noose over his head and tightened the knot. The bailiff nodded, and stepped back, beside the priest, who had forgotten to pray in horror at what he was watching. The drum roll started again, and the trapdoor was released. Hodge's body shot through the gap, and jerked there at the end of its rope, legs flailing for a moment to suggest that the knot had not been accurately placed.

A great moan arose from the slaves; but it was of amazement rather than pity, and it was immediately overtaken by the shriek of anger from the whites as they surged forward, were met by the bayonets of the marines, and turned to vent their rage on Government House.

But the balcony was empty. The watchers had returned inside.

‘It

's done, then.' Hugh Elliott poured three glasses of wine. 'You must be a proud man, Matt.'

'Aye.' Matt Hilton looked into his glass for some seconds before he drank. 'If I knew what I

had

done.'

'Doubts?'

'And well he should have doubts,' Robert Hilton remarked. 'Do you think any of those niggers will forget what they have just seen? Do you think the West Indies will ever forget it? If a white man can be hanged for killing a slave, then there is not a man of us who does not deserve to change places with that blackguard. You know that, Hugh, as well as Matt does.'

'Yet was Hodge a bigger scoundrel in his sleep than you ever were when awake, Robert,' Elliott insisted. 'He was not hanged for murder, and you know that. He was hanged for the systematic ill-treatment of his people. If his death encourages but the slightest spark of humanity in the plantocracy, then it was well done.'

'And the woman?' Robert asked.

'She is pregnant, and cannot be executed, at least not for a long time. Thus I have not even charged her. I do not think those people would have stood for it, anyway.'

'She is more of a rascal than was her husband,' Matt said, softly.

‘

O

h,

indeed,' Elliott agreed. 'But we'll hear no more of her. The plantation is up for sale. She'll go back to England, I have no doubt. Would you see her?'

'Not I,' Matt said. 'I saw Hodge, and that was enough.'

'I would like to see her,' Robert said.

His cousin and the Governor looked at him in surprise.

'She'll get naught for the plantation,' Robert said.

'And you feel that her well-being is your concern?' Elliott demanded.

Robert Hilton flushed, a sufficiently rare sight.

‘I

wish to be sure we performed justice here today, and not merely satisfied a personal vendetta.'

Elliott hesitated, glanced at Matt, and then shrugged. 'You'd best come along then.' He led them down the stairs and through a covered passageway towards the courthouse. Here the noise of the still shouting crowd was muted, and even the heat of the afternoon was dwindling amidst the cool, damp stone.

The gaoler threw open the doors, and they walked between the cells, stared at by the white man imprisoned for assaulting his wife, by the two free blacks awaiting trial for smuggling, and reached the end, to gaze at the woman, short and thin and sallow-skinned, hair straggling in rat-tails on her shoulders, bare feet soiled with dust, white gown a mass of rents and dirty stains. She sat on her cot bed, only glanced up as the men arrived, and then scrambled to her feet and backed against the wall as she recognized them.