Hieroglyphs (12 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

how hieroglyphs can have a vagueness in their detail.

2

The reader had to be aware of when such differences might have meaning and when they might not. For example,

an arm and hand holding a

stick is very different in potential meaning (determinative for

‘strength’ or violent action) from an arm and hand holding a specific staff or sceptre,

(supervising actions). On the other hand the

sign is also a determinative for ‘strength’ or violent actions. The standing man is a tall vertical sign and the arm long and horizontal, so that the space available in the whole writing of the word may have affected the choice of sign. But was there really any difference in their meaning? Knowledge of such differences came through practice and experience and had to be learnt.

Literacy and access

Most of the Egyptian population were field workers, herdsmen, or craftsmen who lived in dispersed agricultural settlements up and

phs

down the Nile Valley and in the less marshy delta areas. They lived

ogly

off what they grew, supplied surpluses for the royal and temple

Hier

landowners and had access to good supplies of basic commodities at a local level. They did not have access to the resources of the élite, including the ability to have stone tomb monuments for their personal commemoration. As many hieroglyphic texts were written in monumental contexts such as tombs and temples the mass of Egyptians had restricted access to them. It has been estimated from the occurrence of élite monuments with writing on them that in the Old Kingdom only around 1 per cent of the population was literate, that is, could read and write at all, and possibly for hieroglyphs the figure was even lower. At the most basic level, the ability to read and write one’s name may have been more widespread, particularly for administrative purposes, and this writing would almost certainly have been in hieratic not hieroglyphs.

The tombs of the élite were often in special necropolis areas. In the Nile Valley this would frequently be the desert edge, perhaps visited only by close relatives who took part in funerary offerings and feasts 50

and in the performance of rituals. If they were of the same social standing they might read and may even have recognized themselves and other people depicted in the tomb. The son of the dead man (or a literate substitute) would have had to be able to recite an offering prayer for his father. On the outer door jambs and lintels of some tombs or in funerary stelae there are sometimes specific calls to the passer-by to make sure that the offerings are continued in the tomb for the dead person’s

ka

. They begin, ‘O all the living who pass by or who enter in this tomb . . .’, and may have been intended to function after the immediate family had passed away and were no longer able to continue the cult. Once the living had departed, the writing and its properties were intended to function, continually activating and providing the food and necessary goods for the dead person in the afterlife. Ultimately, the audience was only the spirits (

kas

) of the dead and they depended on the few

ka

-priests and lector priests whose job it was to read out the relevant rituals. For the visitors to

Hieroglyp

such places, the visual impact must have been very striking, a marker of a sacred zone with messages about status and life

hs an

after death.

d ar

t

In temples the audience was even more restricted. ‘Ordinary’

Egyptians were not allowed into the temple complexes as they were impure. The priests appointed as ‘servants of the gods’ were specifically supposed to be purified before they entered the temple.

Once inside, they performed rituals to ensure that the temple god was cared for and enjoyed regular meals and festivals. Many of the special prayers and rites were written on the walls and in papyrus scrolls from which they were read out by the ‘lector-priest’. Some of the prayers could have been learned by heart, so that even a priest who served only a short time in the temple may have needed relatively little ability to read the texts on the walls. In any case, much of the temple would have been dark and gloomy, with only the play of light through the narrow openings in the roof onto small sections of the wall at any one time, or the flicker of lamplight on the walls, to illuminate the texts. They were, after all, intended for the eyes of the gods and for them alone. In this case, hieroglyphs 51

truly are ‘the words of the gods’, providing the medium of communication between the ordinary world and the supernormal.

The presence of hieroglyphs acts as a status marker. The most extreme form of status, being divine, implied an all-embracing knowledge and magical power which could interact with the scenes and texts on temple walls. The rituals activated the hieroglyphs, so that by the scent and smoke of burning incense the very writing could be inhaled by the gods; poured water soaked into the offerings and the fabric of the temple, energizing and bringing life; the provision of food, with its smells and taste, activated the senses and power of the gods. Not just each single hieroglyph, but also the two-dimensional reliefs, the three-dimensional statues, and the physical enactments and rituals were all ‘read’ to fulfil the function of the temple. In a way, each was also a back-up for the other, should they fail for some reason. The pragmatic Egyptians realized that in order to make the house of the god endure after they had gone, they

phs

needed the medium of writing to continue their work. In essence,

ogly

the temple walls continue to provide the energy for the gods and the

Hier

hieroglyphs continue, even to this day, before the innocent eyes of tourists and guardians, to mediate with the gods of Egypt.

The exterior walls of the temples presented a different world and the acres of space on the high, stone enclosures of temples with the impressive mountain-like pylons as the entrance gave a huge canvas for scenes and texts. They were decorated with very particular scenes which served a purpose in terms of the cosmic dimension of the temple and perhaps as a giant advertising hoarding for those on the outside. These scenes showed the king destroying his enemies and the forces of chaos before the gods, either by personally dispatching them or by fighting them in battles. In vivid colours, made luminescent in the strong Egyptian sunlight, they would have provided a gaudy and living panoply of war and conquest to anyone within the temple complex. More people were allowed into this part of the temple than into the inner house of the god. The message of these advertisements is that the king had conquered his foes, chaos 52

had been removed to the outside of the temple realm, and

maat

,

‘cosmic harmony’, was maintained.

Technically, the small print was irrelevant. The viewer could take in the message in one glance, but it was still inscribed for the gods themselves to read. These texts hardly need any hieroglyphs, yet they have them, identifying individuals, describing the scenes, listing the names of the defeated enemy and giving the tallies of the dead and captured in the battle scenes. Such images occupy their proper place and give the message that the king is fulfilling his part of the bargain with the gods by keeping chaos at bay. As a result, everyone could be reassured that the gods would continue to allow the Nile inundation to come and the sun to continue its daily cycle across the heavens. In the Egyptian psyche, this may have meant that the investment of the Egyptian people in the power of their king was worth it, as it was proved to work. The giant hieroglyphs

Hieroglyp

spell out the bargain of man and gods and the control of the king over his Egyptian people.

hs an

d ar

Inevitably, the status conferred by writing is most powerfully felt

t

nearest to the king and the court. The tombs of his officials are covered in writing. As one moves away from this power base it is possible to see what has been termed a more ‘provincial’ type of writing and hieroglyphs. It has been suggested that examples of

‘provincial’ art and writing occurred mostly at times when central authority in the country was weakening and local provincial governors took on a role and status more like those at the central royal court. The style of art shows a lack of proportion in the drawing of figures: they have disproportionately large heads with huge eyes, the body is drawn in a stick-like fashion, and the quality of the hieroglyphs is bad. The text can be written randomly and without baselines or structured register lines and they can be so poorly drawn that they are sometimes scarcely recognizable. The funerary stelae of the governors of Dendera and the nomes of Middle Egypt during the First and Second Intermediate periods show these tendencies. Nevertheless the functions of these pieces of 53

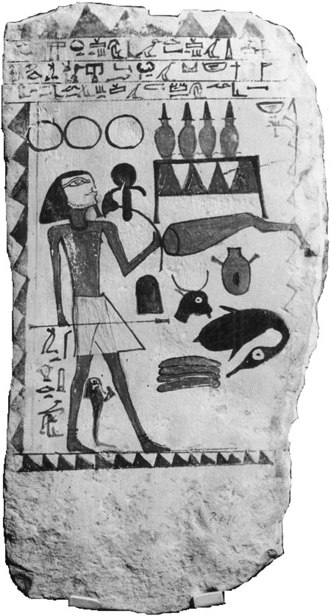

11. Stela of Montuhotep, from Er-Rizeqat, Middle Egypt, Second

Intermediate Period.

writing remains the same. While they may not preserve the aesthetic merit of the Saqqara necropolis two or three hundred miles away, for people who would never have the chance to leave their home village or town this writing was as real as it could be.

After all, in modern times tourists are happy to come away from their holiday destinations with locally produced papyri or to wear fashionable clothes adorned with kanji characters which they cannot read or understand. The love of the exotic, the personally meaningful, and the aesthetically pleasing is a human quality which persists through the ages.

At Er-Rizeqat a man called Montuhotep employed an artist to produce a fitting monument for him. The artist produced a vibrantly coloured stela that would give him status and enhance his local standing – and anyone who had never seen such a stela would be no wiser as to its quality. The fact of its existence, with

Hieroglyp

linear hieroglyphs and not full hieroglyphic script, was enough for personal propaganda purposes, both in this life and the next.

hs an

d ar

t

55

A number of papyrus fragments and other texts from the New Kingdom preserve the story of ‘The Cunning of Isis’. As the consort and sister of Osiris, Isis had great magical abilities, including that of being able to revivify the mummified body of her husband sufficiently to enable her to conceive their son, Horus. As the avenger of his father, Horus was embodied in the person of the king of Egypt. The role of Isis in this important ideological framework was paramount and ‘The Cunning of Isis’ gives a mythological version of how she came to gain her magical powers. Isis manufactured a serpent from mud mixed with the spittle of the sun god, Re, who at the time of this tale (perhaps in the evening) was old and tending to drool. She left the serpent on the pathway where the sun god would walk each day. When Re passed by, the serpent stirred and stung the god. Serpent bites are not necessarily fatal and especially not to sun gods, but they can hurt and Re was in agony. Isis, as the healer, came to see her father and diagnosed a serpent bite. She claimed, however, that she could only cure Re if he told her his secret name: ‘A man lives when one recites in his name.’

1

Re, in fact, had many names and forms. He had one name for each hour of the day and perhaps more than that, but he also had a secret name which gave him invincibility. In order to remove 56