Hieroglyphs (13 page)

Authors: Penelope Wilson

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #Ancient, #Social Science, #Archaeology, #Art, #Ancient & Classical

the pain, Re whispered his names to Isis and she accordingly constructed a spell, including the names to take away the pain.

She knew, however, that Re would never give up his hidden name so easily and therefore her spell was ineffective. She went back to her father and said that as he had not told her his true ‘secret’

name, the pain would continue. This time Re gave in and whispered his true secret name to her, which she incorporated into her spell. It then worked, releasing the sun god from his agony. At the end of this episode, Re was healed, but Isis still knew the secret name of Re. The implication of the myth is that this was the basis of her power.

This colourful story, full of allusion and subtlety, like most Egyptian myths, is founded on the basic principle that the name

‘I kno

of a person contains the essence of that person. In addition, the

w y

knowledge of the name can invoke the being of an individual for

ou, I kno

good or for bad. For those people who were of sufficient status to have their names written in hieroglyphs, the extra magical power

w

of the hieroglyphs was a potent mixture. A statue or relief

yo

sculpture or drawing could be an image of anyone. As soon as it

ur nam

was identified with a name, written in hieroglyphs or hieratic, it

es’

gave identity to that image and image to that individual. Like the grammatical determinative, it determined ‘who’ a person was.

In part, this explains the idealized images which we associate with Egyptian art. The lithe men and women portrayed in statues and the portly officials at work in their tombs are not ‘portraits’ of real people but ideal images of themselves as persons of rank and status identified by their names and titles. Portraits do exist but within the framework created by this principle. The name means that the image can be recognized by various entities and this is of paramount importance in the tomb and funerary context and also in the temple, both the main arenas for the writing of hieroglyphs.

In the tomb chapel, the cult of the deceased was maintained by priests and relatives after the death of the tomb owner. Here 57

they made food and liquid offerings and burnt incense, nourishing the spirit of the dead in the afterlife and stimulating their senses.

However, the focal parts of the cult, the false door, stela, and offering table, all contain the name of the dead and these elements provide the point of contact with the dead and with the ‘correct’

individual, labelled by the hieroglyphs. From the other side of the afterlife, the

ka

and the

ba

recognized this refuelling point by the hieroglyphs naming the particular person. The hieroglyphs communicate the correct information and ensure that the dead continue to be fed, watered and anointed in the afterlife.

Within the temple, the images of the gods were named on the walls, ensuring that they took part in the correct rituals and took their places in the cosmic symmetry of the temple. To some extent, the naming of these images brings them to life, activates them and makes the roving essence of the gods immanent within their

phs

images, be they falcon statues, as at Edfu Temple, or Hathor reliefs,

ogly

as at Dendera. It seems to have been important that each being was

Hier

in its correct place.

The opposite of this idea was also appreciated by the Egyptians. If it were true that hieroglyphs in themselves were images of animals, people, birds, and even reptiles and that hieroglyphs were imbued with some kind of animating power, could it not also be the case that these creatures could come to life on the tomb walls where they were written? In this case might they not threaten the dead person and their continued existence? Indeed, this was believed to be the case and in the Pyramid Texts of Dynasty 5 written inside the burial chambers of the pyramids of kings such as Teti or Pepi I, the animal hieroglyphs were individually mutilated. The animal signs were written without legs, birds had their heads cut off, knives were inserted into the bodies of snakes or crocodiles, human figures were drawn incomplete, and sometimes certain signs were completely substituted if they could not be disabled in some other way.

58

Taking this idea further, the complete removal of the name of a person could also remove their existence. If the name of a tomb owner were scratched away, his

ka

would not recognize its images and could not be nourished and therefore the dead person would not live in the afterlife. Their name, the memory of them, and their cult would indeed be forgotten and their being would be inanimate. Clearly, this was an act of condemnation, sending a person to their second death, the most feared end for any human life. It was used in Egypt against both human beings and gods as a political and religious act of denial of existence.

Hatshepsut ruled Egypt on behalf of her stepson, Thutmose III, and assumed the full regalia and titles of ‘King’. Yet, some time

‘I kno

after her death her names and images were scratched out from

w y

many of the temples she had built and even in her mortuary

ou, I kno

temple, designed to continue her afterlife existence. The exact reasons for this can only be guessed at, but the effect is undeniable.

w

Someone was trying to erase her memory, so that she would not

yo

exist in the minds or eyes of people in this life or in the next.

ur nam

Similarly, after the reign of Akhenaten, his name and images were

es’

systematically removed from his city at Akhetaten and also from his monuments at Karnak.

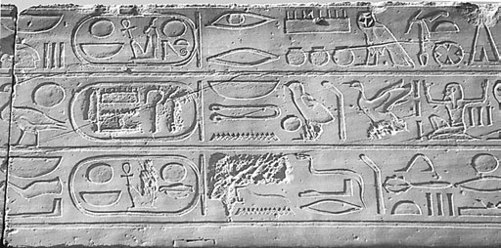

12. Examples of the erasure of the name of Amun from the architraves

of a colonnade in Luxor Temple.

59

The

damnatio memoriae

had been a favourite weapon of Akhenaten himself during his reign when he turned to the worship of the sun disk, the Aten, and apparently away from the previous state god, Amun. He had ordered the removal of the name of Amun from wherever it occurred, particularly in the heartland of the god at Thebes and among the supporters of the old religio-political order. Many of them had names compounded with the name of Amun, such as ‘Amun-em-het’, ‘Amun is to the front’, and even his father had been called ‘Amun-hotep’, ‘Amun is content’. Nothing was safe and Amun was scratched out in tombs and temples, on statues and objects in a truly literal gesture of ‘rubbing him out’.

In the context of the tombs it almost casually removed the afterlife existence of the person too.

The denial of existence was a strong political gesture in a culture where such beliefs permeated political and social situations and institutions. It seems to have been one of the worst things which

phs

could be done to a person and the fact that so many texts mention

ogly

the hope that names will continue to exist suggests that the fear of

Hier

losing the written name went deep. Even Akhenaten himself acknowledged it in his boundary stela at Akhetaten, saying of the inscription, ‘It shall not be scratched out, it shall not be washed off, it shall not be hacked out, it shall not be washed over with gypsum-plaster. It shall not be lost and if it is lost, if it disappears, or if the stela on which it is falls down, I shall renew it again as a new thing in this place where it is’.

2

Power and the written word

In magical rituals the gestures, dancing, incantation, smoke, and magical objects were not enough to make some spells work. They needed the extra power of written hieroglyphs. A lector priest’s toolkit from a Middle Kingdom tomb under the Ramesseum at Thebes consisted of a box containing all the paraphernalia for invoking power. There were fertility figures, ivory ‘wands’ covered in bizarre and fantastic creatures, a cowherd figure, a copper serpent, 60

and a figure of a woman wearing a lioness mask and holding two serpent wands in her hands. Together with these objects were papyri covered in texts in hieratic, including literary works and magical texts. Whoever owned this box was a trained scribe with a sideline or maybe a job in providing magical services for people at Thebes. It is the association of the gear and the written material which is so fascinating. This person, most likely to be a man, possibly with a female helper as suggested by the lioness-masked figure, would have been called out to help in times of births, to offer fertility rituals, to offer cures in the case of snake or scorpion bites or other afflictions. The written spells could provide the authority for the rest of the activities and no doubt there were specific

incantations for specific purposes.3

‘I kno

In a more sinister light there is a class of object from Egypt called

w y

‘Execration Figures’. They were made of mud or stone and were

ou, I kno

often in the form of enemy prisoners with their hands tied behind their backs. They would have spells against ‘enemies’, or ‘ills’,

w

written on their bodies and then they would be broken and smashed

yo

into pieces, so that the named enemies were completely destroyed.

ur nam

It is possible that these figures relate to general ills and evils,

es’

especially as a kind of perceived threat from ‘foreigners’, and so they are a general protection for Egyptians. They are a more institutionalized form of racist hatred or fear, particularly as shown in the horrifying Mirgissa burial of a decapitated Nubian with all the hallmarks of a ritual slaughter, accompanied by magic. The ritual most likely involved a set of prescribed gestures and spoken words read out from a scroll or recited from memory. It is no accident that from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods it is the god of writing, Thoth, who is most closely associated with magical ritual, surviving into medieval thought as Hermes Trismegistus.

The inherent power of hieroglyphs to transform themselves or animate is adopted in the Memphite story of the creation of the world. Here, Ptah was believed to have first created everything by simply thinking of the names of things, then speaking their names.

61

At the moment of his speaking the names of things and beings they came into existence and the world was created with all its plants, people, and animals. It is perhaps significant that this ‘Memphite Theology’ survives, copied onto stone supposedly from an older

‘worm-eaten’ papyrus scroll now lost. The stone was inscribed in the reign of the Nubian king, Shabako (712–702 bc) and highlights the interest of the later rulers in the ‘ancient’ writings of the past.

4 Th

e Demotic story cycle of Setne Khaemwese centres on the search for a book written by Thoth himself which contained two powerful spells.

According to the story, the reader of this book would be able to charm all the cosmos and understand the words of birds and reptiles, perhaps a me

taphorical allusion to being able to understand hieroglyphs.5

Playing with words, text, and signs