History of the Second World War (22 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The radiance of victory, however, was soon dimmed. The complete extinction of Graziani’s army had left the British with a clear passage through the Agheila bottleneck to Tripoli. But just as O’Connor and his troops were hoping to race on there — and throw the enemy out of his last foothold in North Africa — they were finally stopped by order of the British Cabinet.

On February 12 Churchill sent Wavell a long telegram which, after expressing delight that Benghazi had been captured ‘three weeks ahead of expectation’, directed him to halt the advance, leave only a minimum force to hold Cyrenaica, and prepare to send the largest possible force to Greece. Almost the whole of O’Connor’s air force was removed immediately, leaving only one squadron of fighters.

What had produced this somersault? General Metaxas had died suddenly, on January 29, and the new Greek Prime Minister was a man of less formidable character. Churchill saw an opportunity of reviving his cherished Balkan project, and was prompt to seize it. He again pressed his offer on the Greek Government — and this time they were persuaded. On March 7, with Wavell’s agreement and the approval of the Chiefs of Staff and the three Commanders-in-Chief, Middle East, the first contingent of a British force of 50,000 troops landed in Greece.

On April 6 the Germans invaded Greece, and the British were quickly driven to a second ‘Dunkirk’. They narrowly escaped complete disaster, being evacuated by sea with great difficulty, leaving all their tanks, most of their other equipment, and 12,000 men behind in German hands.

O’Connor and his staff were confident that they could have captured Tripoli. Such an advance required the use of Benghazi as a base-port and some of the transport there had been reserved for the gamble in Greece. But all this had been worked out. General de Guingand, who later became Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, has revealed that the Joint Planning Staff in the Middle East were convinced that Tripoli could be captured and the Italians swept out of Africa before the spring.

General Warlimont, a leading member of Hitler’s staff, has revealed that the German Supreme Command took the same view:

We could not understand at the time why the British did not exploit the difficulties of the Italians in Cyrenaica by pushing on to Tripoli. There was nothing to check them.* The few Italian troops who remained there were panic-stricken, and expected the British tanks to appear at any moment.

*Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

p. 250

n.

On February 6, the very day that Graziani’s army was being finally wiped out at Beda Fomm, a young German general, Erwin Rommel — who had brilliantly led the 7th Panzer Division in the French campaign — was summoned to see Hitler and told to take command of a small German mechanised force that was to be sent to the Italians’ rescue. It would consist of two small-scale divisions, the 5th Light and the 15th Panzer. But the transportation of the first could not be completed until mid-April, and that of the second not until the end of May. It was a slow programme — and the British had an open path.

On the 12th Rommel flew to Tripoli. Two days later a German transport arrived, carrying a reconnaissance battalion and an anti-tank battalion, as a first instalment. Rommel rushed them up to the front, and backed up this handful with dummy tanks that he quickly got built, in the hope of creating an air of strength. These dummies were mounted on Volkswagens, the ‘people’s motor-car’ that was cheaply mass-produced in Germany. It was not until March 11 that the tank regiment of the 5th Light Division arrived in Tripoli.

Finding the British did not come on, Rommel thought he would try an offensive move with what he had. His first aim was merely to occupy the Agheila bottleneck. This succeeded so easily, on March 31, that he decided to push on. It was evident to him that the British much overestimated his strength — perhaps deceived by his dummy tanks. Moreover the Germans had the balance of strength in the air, which helped to conceal from the British command their weakness on the ground, and led also to some of the misleading reports rendered by the R.A.F. during the subsequent battles.

Rommel was lucky, too, in his timing. The 7th Armoured Division had been sent back to Egypt at the end of February to rest and refit. Its place was taken by part of the newly arrived and inexperienced 2nd Armoured Division — the other part had gone to Greece. The 6th Australian Division had been sent to Greece, and the 9th which replaced it was short of both equipment and training. O’Connor too had been given a rest, and had been relieved by Neame, an untried commander. Moreover Wavell, as he later admitted, did not credit reports of an impending German attack. The figures justified his view, and he can hardly be blamed for not making allowance for a Rommel.

Disregarding higher orders to wait until the end of May, Rommel resumed his advance on April 2, with fifty tanks, followed up more slowly by two new Italian divisions. By mobility and ruse he sought to magnify his slight strength. Following the shock of Rommel’s initial assault, his shadow loomed so large that his two slim fingers, nearly a hundred miles apart, became magnified into encircling horns.

The effect of this audacious thrust was magical. The British forces hastily fell back in confusion, and on April 3 evacuated Benghazi. In this emergency O’Connor was sent up to advise Neame, but in the retreat their unescorted car ran into the back of a German spearhead group, on the night of the 6th, and both were taken prisoner. Meanwhile the one British armoured brigade had lost almost all its tanks in the long and hasty retreat, while the next day the commander of the 2nd Armoured Division, with a newly arrived motor brigade and other units, was surrounded at Mechili and led to surrender — the strength of the encircling force being magnified by the dust-clouds that Rommel’s men raised, with lines of tracks, to disguise their weakness in tanks. The Italians were still lagging behind.

By April 11 the British were swept out of Cyrenaica and over the Egyptian frontier, except for a small force shut up in Tobruk. This was in its way as astonishing a feat as the earlier conquest of Cyrenaica, and had been even quicker.

The British had now to begin all over again their efforts to clear North Africa, and under much heavier handicaps than before — above all, the presence of Rommel. The price to be paid for forfeiting the golden opportunity of February 1941 was heavy.

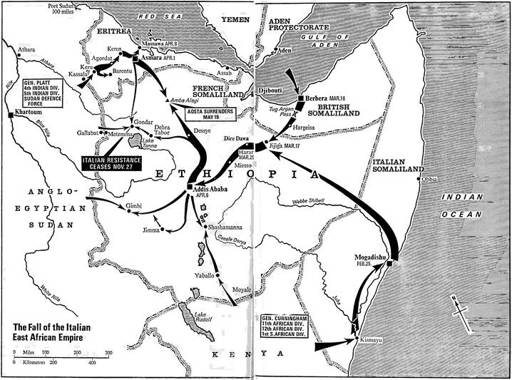

CHAPTER 10 - THE CONQUEST OF ITALIAN EAST AFRICA

When Fascist Italy entered the war in June 1940 on Mussolini’s instigation, her forces in Italian East Africa — which since 1936 had included conquered Ethiopia — immensely outnumbered the British, as they did in North Africa. According to the Italian records the forces in that area amounted to some 91,000 white troops and close on 200,000 native troops — although the latter seems to have been largely on paper, and might more reasonably be estimated as about half the claimed number. In the early months of 1940, preceding Italy’s entry into the war, the British strength was only some 9,000 British and native troops in the Sudan, and 8,500 British East African troops in Kenya.

In this vast theatre of war, a double theatre, the Italians were almost as slow to take the initiative as they were in North Africa. A prime reason was their awareness that they were unlikely to get further supplies of motor fuel and munitions through the British blockade. But that was hardly a good reason since it made it more important to exploit their great superiority of strength before the British forces in Africa could be adequately reinforced.

Early in July the Italians moved hesitantly forward from Eritrea, in the north-west, and occupied the town of Kassala, a dozen miles inside the Sudanese frontier, employing a force of two brigades, four cavalry regiments, and two dozen tanks — some 6,500 men — against an outpost held by a company, of about 300 men, of the Sudan Defence Force. Major-General William Platt, commanding in the Sudan, had then only three British infantry battalions for the whole of that large area, posted respectively at Khartoum, Atbara, and Port Sudan. Wisely, he did not throw them into the fight until he could see how the Italian invasion developed. Instead of pushing on, it stopped — after occupying a few other frontier posts such as Gallabat, just over the north-west frontier of Ethiopia, and Moyale, on the northern frontier of Kenya.

It was not until early in August that the Italians started a more serious offensive move, and that was launched against the easiest possible target — British Somaliland, the strip of coastal territory on the African shore of the Gulf of Aden. Even that very limited move was defensive in motive. Indeed, Mussolini had ordered the Italians to stay on the defence. But the Duke of Aosta, who was Viceroy of Ethiopia, and supreme commander in that area, felt that the French Somaliland port of Djibouti offered an easy entry for the British into Ethiopia, and did not trust the armistice agreement with the French. So he decided to occupy the adjoining and larger area of British Somaliland.

The British garrison there, under Brigadier A. R. Chater, consisted of only four African and Indian battalions, with a British battalion, the 2nd Black Watch, on the way. The Italian invading force comprised twenty-six battalions provided with artillery and tanks. But the small Somaliland Camel Corps effectively delayed its advance, and Major-General A. R. Godwin-Austen arrived on the scene to take over just as the invaders reached the Tug Argan Pass on the approaches to Berbera, the seaport capital. Here the defenders put up such a tough defence that the attackers were kept at bay in a four-day battle, but in default of further reinforcements or defensive positions, the British force was evacuated by sea from Berbera — most of it being shipped to augment the British build-up now taking place in Kenya. It had inflicted over 2,000 casualties at a cost to itself of barely 250, and left an impression on the Italians that had a far-reaching strategic effect on their future action.

The British forces in Kenya, under Lieutenant-General Sir Alan Cunningham, who took over in November 1940, comprised the 12th African Division under Godwin-Austen (1st South African, 22nd East African, and 24th Gold Coast Brigades), shortly reinforced by the 11th African Division.

By the autumn the forces in Kenya had been raised to about 75,000 men — 27,000 South Africans, 33,000 East Africans, 9,000 West Africans, and about 6,000 British. Three divisions had been formed — the 1st South African, and the 11th and 12th African. In the Sudan there was now a total of 28,000 troops, including the 5th Indian Division, while the 4th Indian was to move there after taking part in the initial stage of the brilliant counterstroke against the Italians in North Africa. A squadron of tanks had been sent there from the 4th Royal Tanks. There was also the Sudan Defence Force.

Mr Churchill felt that such large British forces demanded more activity than had been shown, and he repeatedly pressed for more aggressive action than had yet been taken, or contemplated. Wavell, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East, proposed in agreement with Cunningham that an advance from Kenya into Italian Somaliland should begin in May or June after the spring rains. Wavell’s doubts were increased by the tough resistance which Platt’s first advance on the northern front had met in November, when launched against Gallabat by the 10th Indian Brigade under Brigadier W. J. Slim, a resolute leader who later became one of the most illustrious high commanders in the war. The initial attack on Gallabat succeeded, but the follow-up attack on the neighbouring post of Metemma suffered a check against an Italian colonial brigade of almost equal strength. That was largely due to the unexpected failure of a British battalion which had just been inserted in this Indian brigade, contrary to Slim’s advice, for supposed stiffening. As later events showed, the Italian forces in this northern sector were much tougher than those elsewhere.

The only hopeful episodes of the winter were the activities of Brigadier D. A. Sandford, a retired officer who had been recalled to service on the outbreak of war, and subsequently sent into Ethiopia to raise revolt among the highland chiefs around Gondar, activities that were supported and extended during the winter by the still more unorthodox Captain Orde Wingate with a Sudanese battalion and his elusive ‘Gideon Force’. The exiled Emperor Haile Selassie was brought back, by air, to Ethiopia on January 20, 1941 — and barely three months later, on May 5, he re-entered his capital, Addis Ababa, in company with Wingate — far earlier than even Churchill had imagined possible.

For under continued pressure from Churchill, and from Smuts in South Africa, Wavell and Cunningham had been spurred to open the invasion of Italian Somaliland from Kenya in February 1941. The port of Kismayu was captured with unexpected ease, thus simplifying the supply problem, whereupon Cunningham’s forces crossed the Juba River, and pushed on some 250 miles to Mogadishu, the capital and larger port, which they occupied barely a week later, on February 25. Here they captured an immense quantity of motor and air fuel, the speed of the advance having forestalled the planned demolitions, as at Kismayu. Good air support was another important factor in the rapid advance.