History of the Second World War (20 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Kesselring launched his second daylight attack against London on the afternoon of the 9th. No. 11 Group was ready for it this time, with nine fighter squadrons in position, while others from No. 10 and 12 Groups co-operated. Interceptions were so successful that most of the German formations were broken up long before they reached London. Less than half the bombers got through, and hardly any of them succeeded in hitting their targets.

Much the most important effect of this new German offensive was the way it eased the strain on Fighter Command, which had been suffering so badly from the Germans’ concentration on it, and was close to breaking point when the Germans switched their effort to the attack on London. The punishment that the capital and its people suffered was to be the saving factor in the preservation of the country’s defence.

Moreover, the disappointing results of September 9 led Hitler once again to postpone his ten-day warning period for the invasion — this time to the 14th, for invasion on the 24th.

Deteriorating weather provided some respite for the London defences, but on the 11th and 14th a number of bombers got through, and fighter interception was so scrappy that the Luftwaffe optimistically reported that Fighter Command’s resistance was beginning to collapse. So Hitler, although putting off the warning date again, postponed it only three days, to the 17th.

Kesselring launched a big new attack in the morning of Sunday the 15th. This time the fighter defence against it was better planned and timed. Although the air armada was assailed all the way from the coast by a series of single or paired squadrons, twenty-two in all, 148 bombers got through to the London area — but they were prevented from dropping their bombs accurately, and most were widely scattered. Then as the Germans wheeled for home, No. 12 Group’s Duxford wing of some sixty fighters swept down from East Anglia, and although losing some of its effect through not yet having gained sufficient height, its massiveness gave the German airmen a shock. In the afternoon, cloud helped the attackers, and a large number bad a clear run to London, where their bombs inflicted much damage, especially in the crowded houses of the East End. But during the day as a whole about a quarter of the bombers were put out of action and many more damaged, often with one or more of the crew being killed or wounded, to be carried back to their base, with a consequent effect on morale at those airfields.

The actual German loss that day, as established in later checking, was sixty aircraft. That was much less than one-third of the figure of 185 triumphantly announced by the British Air Ministry at the time — but it compared very well with the R.A.F. loss of twenty-six fighters (of which half the pilots were saved) and was a much more favourable balance than in recent weeks. Goring, still blaming his fighters, continued to talk optimistically, and estimated that the British fighter force would be finished off in four or five days. But neither his subordinates nor his superiors continued to share his optimism.

On the 17th Hitler, agreeing with Ms Naval Staff that the R.A.F. was still by no means defeated, and emphasising that a period of turbulent weather was due, postponed the invasion ‘until further notice’. The following day he ordered that no more shipping was to be assembled in the Channel ports, and agreed that its dispersal might begin — 12 per cent of the transports (21 out of 170), and 10 per cent of the barges (214 out of 1,918) had been sunk or damaged by British air attacks. On October 12, ‘Sealion’ was definitely postponed until the spring of 1941 — and in January Hitler ruled that all preparations should be stopped except for a few long-term measures. His mind had now turned definitely to the East.

Goring still persisted with his daylight attacks, but the results were increasingly disappointing, despite occasional successes at out-of-the-way ports. The aircraft works at Filton, near Bristol, were severely hit on September 25, and next day the Spitfire factory near Southampton was temporarily wrecked. But a big raid on the 27th against London was a bad failure, and in the last big daylight attack on September 30 only a fraction of the aircraft reached London, while forty-seven aircraft were lost compared with twenty fighters lost by the R.A.F.

After the disappointing results in the second half of September, and his heavy bomber losses, Goring turned to the use of fighter-bombers operating at high altitude. About mid-September the German fighter formations engaged in the battle had been ordered to give up a third of their strength for conversion into fighter-bombers, and a total of about 250 was thus produced. But insufficient time was allowed to retrain the pilots and the bomb-load they could carry was not enough to do much damage, while they were instinctively inclined to jettison their bombs as soon as they were engaged.

The best that could be said for them was that their use temporarily brought a diminution of German losses while keeping up strain on the R.A.F. But by the end of October, German losses were rising again to the old ratio, while the worsening weather was multiplying the strain on the fighter-bombers’ crews, who were operating from improvised and swamp-like airfields. In the month of October the Germans lost 325 aircraft, much in excess of the British loss.

The only serious harassment of Britain was now coming from night bombing by ‘normal’ bombers. From September 9 the 300 bombers of Sperrle’s Luftflotte 3 settled down to a standard pattern, and for fifty-seven nights London was attacked, by an average force of 160 bombers.

Early in November Goring issued new orders that marked a clear change of policy. The air offensive was to be entirely concentrated on night bombing — of cities, industrial centres, and ports. With the release of Luftflotte 2’s bombers, up to 750 bombers became available, although only about a third of the total were employed at a time. As they could afford to fly at a slower speed, and at a lower height, they could carry heavier bomb-loads than in daylight, and as much as 1,000 tons were dropped in a night. But the accuracy was poor.

The new offensive was launched on the night of November 14 with the attack on Coventry. It was helped by bright moonlight as well as by a special ‘pathfinder’ force. But its effectiveness was not equalled in the big attacks that followed on other cities — such as those on Birmingham, Southampton, Bristol, Plymouth, and Liverpool. On December 29 much damage was caused in London, particularly the centre of the City, but attacks then eased off until the weather improved in March. A series of heavy attacks culminated in a very damaging raid against London on the night of May 10, the anniversary of the launching of the 1940 Blitzkrieg in the West. But in the sky over Britain the ‘Blitz’, as it was called, came to an end on May 16 — after which the bulk of the Luftwaffe was sent eastward for the coming invasion of Russia.

The German air offensive from July until the end of October, 1940, had caused much more damage and disruption than was admitted, and the effects would have been even more serious bad there been greater persistency in pressing, and repeating, attacks on the main industrial centres. But it had not succeeded in its object of destroying the R.A.F’s fighter strength and the British people’s morale.

In the course of the Battle of Britain, from July until the end of October, the Germans had lost 1,733 aircraft — not the 2,698 claimed by the British — while the R.A.F. lost 915 fighters — not the 3,058 claimed by the enemy.

CHAPTER 9 - COUNTERSTROKE FROM EGYPT

When Hitler’s attack on the West reached a point — with the breach of the improvised Somme-Aisne front — where the defeat of France became certain, Mussolini brought Italy into the war, on June 10, 1940, in the hope of gaining some of the spoils of victory. It appeared to be an almost completely safe decision from his point of view and fatal to Britain’s position in the Mediterranean and Africa. This was the darkest hour in her history. For although a large proportion of her army in France had escaped by sea, it had been forced to leave most of its weapons and equipment behind, and in that unarmed state faced an imminent threat of invasion by the victorious Germans. There was nothing available to reinforce the small fraction of the British Army that guarded Egypt and the Sudan against the imminent threat of invasion from the Italian armies in Libya and Italian East Africa.

The situation was all the worse because Italy’s entry into the war had made the sea-route through the Mediterranean too precarious to use, and reinforcements had to come by the roundabout Cape route — down the west coast of the African continent and up the east coast into the Red Sea. A small instalment of 7,000 troops, which had been ready for despatch in May 1940, did not reach Egypt until the end of August.

Numerically, the Italian armies were overwhelmingly superior to the scanty British forces opposing them, under General Sir Archibald Wavell who, on Mr Hore-Belisha’s proposal, had been appointed in July 1939 to the newly created post of Commander-in-Chief, Middle East, when the first steps were taken to strengthen the forces there. But even now there were barely 50,000 British troops facing a total of half a million Italian and Italian colonial troops.

On the southerly fronts, the Italian forces in Eritrea and Abyssinia mustered more than 200,000 men, and could have pushed westwards into the Sudan — which was defended by a mere 9,000 British and Sudanese troops — or southwards into Kenya, where the garrison was no larger. Rugged country and distance, together with Italian difficulties in holding down the recently conquered Ethiopians and their own inefficiency, formed the main protection of the Sudan during this perilous period. Except for two small frontier encroachments, at Kassala and Gallabat, no offensive move developed on the Italians’ part.

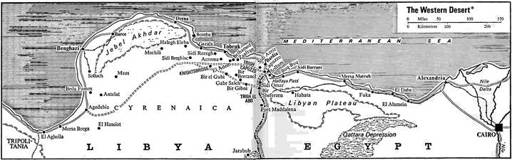

On the North African front a still larger force in Cyrenaica under Marshal Graziani faced the 36,000 British, New Zealand, and Indian troops who guarded Egypt. The Western Desert, inside the Egyptian frontier, separated the two sides on this front. The foremost British position was at Mersa Matruh, 120 miles inside the frontier and some 200 miles west of the Nile Delta.

Instead of remaining passive, however, Wavell used part of his one incomplete armoured division as an offensive covering force right forward in the desert. It was very offensive, keeping up a continual series of raids over the frontier to harass the Italian posts. Thus at the outset of the campaign General Creagh’s 7th Armoured Division — the soon-to-be famous ‘Desert Rats’ — gained a moral ascendency over the enemy. Wavell paid special tribute to the 11th Hussars (the armoured-car regiment) under Lieutenant-Colonel J. F. B. Combe, saying that it ‘was continuously in the front line, and usually behind that of the enemy, during the whole period’.