History of the Second World War (27 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

But the indirect results of the episode were vital, and they reflected on Hitler’s judgement. Operating with such a small margin of force — even when reckoned as quantity × quality — he could not afford to conduct a campaign in Yugo-Slavia and Greece at the same time as his invasion of Russia. A particular handicap was his numerical disadvantage in tanks compared with the Russians. A quick conquest of the Balkans depended on employing panzer divisions, and he would need every one of them that could be collected before he could venture to launch the offensive in Russia. So on April 1 ‘Barbarossa’ was postponed — from the middle of May to the second half of June.

It remains an amazing military achievement that Hitler was able to conquer two countries so quickly that he could keep the new date of entry into Russia. Indeed, his generals considered that if the British had succeeded in holding Greece ‘Barbarossa’ could not have been carried out. In the event, the delay was only five weeks. But it was a factor in forfeiting his chance of victory over Russia, which can be coupled with the Yugo-Slav coup d’etat, a fortuitous delay in August — from indecision of mind — and with the early coming of winter that year.

By May 1 the British had re-embarked from the southern beaches of Greece, save for those who were cut off and captured. That same day Hitler fixed the date of ‘Barbarossa’. His directive summarised the respective strengths and then added:

Estimate of the course of operations

— Presumably violent battles on the frontiers, lasting up to four weeks. In the course of the further development weaker resistance is expected. A Russian will fight on an appointed spot to his last breath.

On June 6 Keitel issued the detailed timetable for the venture. Besides enumerating the forces to be employed in the invasion, it showed that forty-six infantry divisions had been left in the West facing Britain, though no more than one was motorised, and only one armoured brigade had been left there. Operations ‘Attila’ (the seizure of French North Africa) and ‘Isabella’ (the counter to a possible British move in Portugal) could ‘still be executed at ten days’ notice, but not simultaneously’. ‘Luftflotte 2 has been withdrawn from action and transferred to the East, while Luftflotte 3 has taken over sole command in the conduct of air warfare against Britain.’

These orders intimated that negotiations with the Finnish General Staff, to secure their co-operation in the attack, had begun on May 25. The Rumanians, already secured, were to be informed of the final arrangements on June 15. On the 16th the Hungarians were to be given a hint to guard their frontier more strongly. On the following day all schools in eastern Germany were to be closed. German merchant ships were to leave Russia without attracting notice, and outward sailings were to cease. As from the 18th ‘the intention to attack need no longer be camouflaged’. It would then be too late for the Russians to carry out any large-scale reinforcement measures. The latest possible time for the cancellation of the offensive was given as 1300 hours on the 21st, and the codeword in that contingency would be ‘Altona’ — for starting the attack it would be ‘Dortmund’. The hour fixed for crossing the frontier was 0330 on the 22nd.

Despite German precautions, the British Intelligence Service obtained remarkably good information of Hitler’s intentions long in advance, and conveyed it to the Russians. It even accurately predicted the exact date of the invasion — a week before it was finally fixed. But its repeated warnings were received with an attitude of disbelief, and of continued trust in the Soviet-German Pact, which the British found as baffling as it was exasperating. They felt that the Russian disbelief was genuine — that feeling was reflected in Churchill’s broadcast when the news of Hitler’s attack came — and when the Red Army suffered initial disasters they ascribed these partly to the results of it being taken by surprise.

A study of the Russian press and broadcasts would hardly have supported that impression. From April onwards they contained significant indications of precautionary measures, while showing an awareness of German troop movements. At the same time there were much more prominent references to Germany’s strict observance of the Pact, combined with denunciations of British and American attempts to sow discord between Russia and Germany, especially by spreading rumours of German preparations to strike at Russia. A broadcast of this nature on June 13, in Stalin’s distinctive style, remarked that ‘the despatch of German troops into the east and north-east areas of Germany must be assumed to be due to motives which have no connection with Russia’ — a remark that might well encourage Hitler to assume that his deception programme had here succeeded in making the desired impression. Double bluff can be met by redoubling. The same broadcast answered foreign reports of the call-up of Russian reservists by explaining that this was merely for training prior to the usual summer manoeuvres. On the 20th Moscow wireless gave a glowing account of the military exercises that were in progress, near the Pripet Marshes — which may have been calculated to fortify confidence at home. It also announced that the civil air raid defences of Moscow were to be tested ‘under realistic conditions’ on Sunday, the 22nd. Even so, foreign reports of a coming German invasion were once again described as ‘delirious fabrications by forces hostile to Russia’.

The Germans were informed of the British efforts to warn the Russians. Indeed, on April 24 their naval attache in Moscow reported: ‘The British Ambassador predicts June 22 as the day of the outbreak of war.’ But this did not lead Hitler to vary the date. He may have reckoned on the Russians’ discounting any report from British quarters, or have felt that the actual day did not matter.

It is difficult to gauge how far Hitler believed that the Russians were unprepared for his blow. For he often veiled his thoughts from his own circle. Reports from his observers in Moscow had been telling him since the spring that the Soviet Government was apprehensively passive and anxious to appease him; that there was no danger of Russia attacking Germany as long as Stalin lived. As late as June 7 the German Ambassador there reported: ‘All observations show that Stalin and Molotov, who alone are responsible for Russian foreign policy, are doing everything to avoid a conflict with Germany.’ Confirmation of this seemed to come not only from the way the Russians were keeping their deliveries under the trade agreement, but by their sops to Hitler of withdrawing diplomatic recognition of Yugo-Slavia, Belgium, and Norway.

On the other hand, Hitler often declared that Nazi diplomats in Moscow were the worst-informed in the world. He also furnished his generals with reports of an opposite nature — that the Russians were preparing an offensive, which it was urgent to forestall. Here he may have been deliberately deceiving them, rather than believing the reports himself, for he was having continued difficulty with his generals, who were still putting up arguments for abstaining from the invasion. Or a belated realisation that the Russians were not so unready as he had hoped may have led him, on the rebound, to assume that their intentions were similar to his own. After crossing the frontier the generals found little sign of Russian offensive preparations near the front, and thus saw that Hitler had misled them.

CHAPTER 13 - THE INVASION OF RUSSIA

The issue in Russia depended less on strategy and tactics than on space, logistics, and mechanics. Although some of the operational decisions were of great importance they did not count so much as mechanical deficiency in conjunction with excess of space, and their effect has to be measured in relation to these basic factors. The space factor can be easily grasped by looking at the map of Russia, but the mechanical factor requires more explanation. A preliminary analysis of it is essential to the understanding of events.

As in Hitler’s previous invasions everything turned on the mechanised forces, though they formed only a small fraction of the total forces. The nineteen panzer divisions available amounted to barely one tenth of the total number of divisions, German and satellite. The vast residue included only fourteen that were motorised and thus able to keep up with the armoured spearheads.

Altogether the German Army possessed twenty-one panzer divisions in 1941 compared with ten in 1940. But that apparent doubling of its armoured strength was an illusion. It had been achieved mainly by dilution. In the Western campaign the core of each division was a tank brigade of two regiments — each comprising 160 fighting tanks. Before the invasion of Russia a tank regiment was removed from each division, and on each ‘rib’ a fresh division was formed.

Some of the best qualified tank experts argued against the decision, pointing out that its real effect was to multiply the number of staffs and of unarmoured auxiliary troops in the so-called armoured forces while leaving the scale of armoured troops unchanged, and thus diminishing the punch that each division could deliver. Of its 17,000 men, only some 2,600 would now be ‘tank men’. But Hitler was obdurate. Seeing the vastness of Russia’s spaces he wanted to feel that he had a larger number of divisions that could strike deep, and he reckoned that the technical inferiority of the Russian forces would compensate the dilution of his own. He could also stress the fact that owing to the increasing output of the later Mark III and Mark IV types, two-thirds of the armoured strength of each division would now consist of medium tanks — with larger guns and doubled thickness of armour — whereas in the Western campaign two-thirds had been light tanks, The power of its punch would thus be increased even though the scale was halved, That was a good argument up to a point, and for the moment.

The reduction in the scale of tanks, however, emphasised the fundamental flaw in the German ‘armoured division’ — that the bulk of its elements were unarmoured and lacked cross-country mobility. The greatest development which the tank had produced in warfare — more important even than its revival of the use of armour — was its ability to move

off

the road, to be free from dependence on the smooth and hard surface of a prepared track. Whereas the wheeled motor-vehicle merely accelerated the pace of marching, and reproduced the effect of the railway in a rather more flexible form, the tank had revolutionised mobility. By laying its own track as it moved it dispensed with the need to follow a fixed route along a prefabricated track, and thus superseded one-dimensional by two-dimensional movement.

The significance of that potentiality had been realised by the original British exponents of mechanised warfare. In the pattern of armoured force they had proposed at the end of World War I all the vehicles, including those which carried supplies, were to be of the tracked cross-country type. Their vision had not been fulfilled even in the German Army, which had done more than any other to make use of it.

In the reorganised panzer division of 1941 there were less than 300 tracked vehicles in all, while there were nearly 3,000 wheeled vehicles, mostly of a road-bound type. The superabundance of such vehicles had not mattered in the Western campaign, when a badly disposed defence suffered a far-reaching collapse and the attacker could profit by a network of well-paved roads in exploiting his opportunity. But in the East, where proper roads were scarce, it proved a decisive brake in the long run. The Germans here paid the penalty for being, in practice, twenty years behind the theory which they had adopted as their key to success.

That they succeeded as far as they did was due to their opponents being still more backward in equipment. For although the Russians possessed a large numerical superiority in tanks, their total quantity of motor vehicles was so limited that even their armoured forces did not have a full scale of motor transport. That proved a vital handicap in manoeuvring to meet the German panzer drives.

The Germans’ armoured strength in this offensive totalled 3,550 tanks, which was only eight hundred more than in the invasion of the West. (The Russians, however, claimed in August that they had destroyed 8,000.) The total Red Army tank strength, according to Stalin’s despatch to Roosevelt of 30 July 1941, amounted to 24,000, of which more than half were in Western Russia.

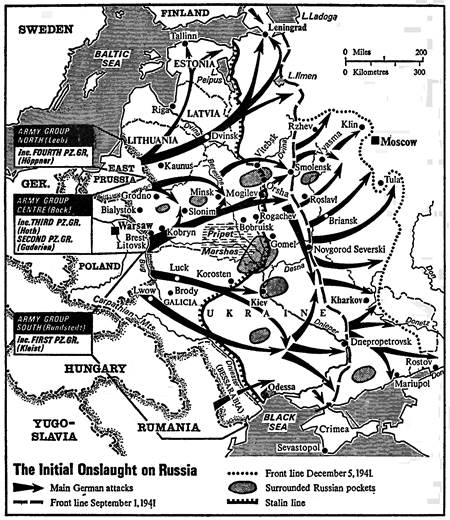

Early on Sunday morning, June 22, the German flood poured across the frontier, in three great parallel surges between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains.

On the left, the Northern Army Group under Leeb crossed the East Prussian frontier into Russian-occupied Lithuania. On the left centre, east of Warsaw, the Central Army Group under Bock started a massive advance against both flanks of the bulge that the Russian front formed in northern Poland. On the right centre there was a sixty-mile stretch of calm, where the German flood was divided by the western end of the Pripet marshland area. On the right, the Southern Army Group under Rundstedt surged forward on the north side of the Lwow bulge formed by the Russian front in Galicia, near the Carpathians.

The gap between Bock’s right and Rundstedt’s left was deliberately left to gain concentration of force and the clearest possible run. The speed of the German advance was thereby increased in the first stage. But since this Pripet sector was left untouched, the Russians were granted a sheltered area where their reserves could assemble under cover, and from which, at a later stage, they could develop a series of flank counterattacks southward which put a brake on Rundstedt’s advance on Kiev. This would have mattered less if Bock’s advance north of the Pripet Marshes had succeeded in its aim of trapping the Russian armies around Minsk.