History of the Second World War (48 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The precipitate British retreat from the frontier, even before Rommel had arrived there, provided both a justification and confirmation of his boldness. It was a most striking demonstration of moral effect — and of Napoleon’s oft-quoted dictum that ‘in war the moral is to the material as three is to one’. For when Ritchie decided to abandon the frontier — ‘to gain time with distance’ as he telegraphed to Auchinleck — he had three almost intact infantry divisions there, a fourth on the way up that was fresh, and three times as many tanks fit for action as the Afrika Korps.

But the shock of the news from Tobruk had caused Ritchie to abandon any attempt to hold the frontier — a decision which he took on the night of June 20, six hours before Klopper’s decision to surrender.

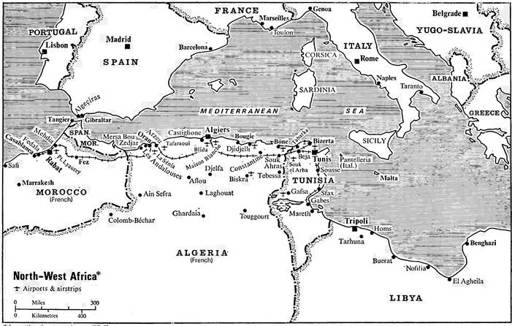

Ritchie’s intention was to make a stand at Mersa Matruh, and fight out the issue there with the divisions brought back from the frontier, reinforced by the 2nd New Zealand Division which was just arriving from Syria. But on the evening of June 25 Auchinleck took over direct command of the Eighth Army from Ritchie. After reviewing the problem with his principal staff officer, Eric Dorman-Smith, he cancelled the order to hold the fortified position at Matruh, and decided to fight a more mobile battle in the Alamein area. It was a hard decision, for not only did it mean many difficulties in getting away troops and stores, but it was bound to cause fresh alarm at home, particularly in Whitehall. In taking this decision, Auchinleck showed a cool head and strong nerve. Although a further withdrawal could not be justified by the balance of material strength, it was probably wise in view of the weaknesses of the Mersa Matruh position, which could be easily by-passed, and of the balance of morale. For although the troops pouring back from the frontier were not demoralised, their confidence was shaken and they were in a state of confusion. Major-General Sir Howard Kippenberger, the New Zealand commander and war historian, watched them arriving in the Matruh area, so ‘thoroughly mixed up and disorganised’ that he ‘did not see a single formed fighting unit, infantry, armour, or artillery’.* Rommel allowed them no time to reorganise, and the speed of his pursuit nullified Ritchie’s reason for abandoning the frontier ‘to gain time with distance’.

* Kippenberger:

Infantry Brigadier,

p. 127.

On getting the ‘release’ from Rome, during the night of June 23/24, Rommel pushed on beyond the frontier and across the desert in the moonlight, and by the evening of the 24th he had covered more than a hundred miles — reaching the coast-road well east of Sidi Barrani, close on the heels of the British, although he only caught a small part of the rear-guard. By the next evening his forces were close to the positions that the British had taken up at Matruh and to the south of it.

Because of the ease with which Matruh could be by-passed, the mobile forces of the 13th Corps (Gott’s) had been posted in the desert to the south, supported by the New Zealand Division, while the Matruh defences were held by the 10th Corps (Holmes) with two infantry divisions. There was a gap of nearly ten miles between the two corps, covered by a minefield belt.

There was no pause to mount a carefully prepared attack. For lack of strength, Rommel had to depend on speed and surprise. While the British armour had been brought up to a total of 160 tanks (of which nearly half were Grants), he had barely 60 German tanks (of which a quarter were light Panzer IIs) and a handful of Italian tanks. The total infantry strength of his three German divisions was a mere 2,500, and that of the six Italian divisions only some 6,000. It was sheer audacity to launch any attack with such a weak force — but audacity triumphed, with the aid of moral effect plus speed.

The three very diminished German divisions, leading the advance, started their attack on the afternoon of the 26th. Two of them had arrived opposite the gap already mentioned. The 90th Light was fortunate in arriving on the shallowest part of the mined belt, and by midnight was twelve miles beyond (it reached the coast-road, again, on the next evening and thus blocked the direct line of retreat from Matruh). The 21st Panzer took longer in getting through the doubled belt of mines that it met, but at daylight drove on twenty miles deep and then swung round on to the rear of the New Zealand Division at Minqar Qaim, scattering part of its transport before being checked. The 15th Panzer, farther south, ran into the British armour and was held in check most of the day. But the swift and deep thrust of the 21st Panzer, and its threat to the British line of retreat, had produced such an effect that in the afternoon Gott ordered a retreat — which soon developed into a very disorderly retreat. The New Zealand Division was left isolated, but succeeded in breaking through the enemy’s thin ring after dark. The 10th Corps in Matruh received no word of the retreat of the 13th Corps until almost dawn on the next day — nine hours after its line of retreat had been blocked. Nearly two-thirds of the Matruh force managed to escape on the following night, however, by breaking out southward in small groups under cover of darkness. But 6,000 were taken prisoner — a number larger than Rommel’s whole striking force — and a vast quantity of supplies and equipment was left behind, to Rommel’s benefit.

Meanwhile his panzer spearheads were pushing on, so fast that they forestalled the British hope of making a temporary stand at Fuka. By their quick arrival on the coast-road there, in the evening of the 28th, they caught and overwhelmed the remnants of an Indian brigade which had been scattered in the opening attack, and next morning they trapped some of the columns that had escaped from Matruh. The 90th Light, which had been mopping up at Matruh, resumed its eastward drive along the coast-road that afternoon; by midnight it had travelled ninety miles, and overtaken the panzer spearheads. Next morning, June 30, Rommel wrote to his wife exultantly: ‘Only 100 more miles to Alexandria!’ By evening he was barely sixty miles distant from his goal, and the keys of Egypt seemed within his grasp.

CHAPTER 20 - THE TIDE TURNS IN AFRICA

On June 30 the Germans moved up close to the Alamein line, a relatively short advance, while waiting for the Italians to arrive. This brief pause to gather strength turned out to the detriment of Rommel’s chances. For that morning what remained of the British armoured brigades were still lying in the desert south of the coast route, unaware that they had been outstripped in their retreat by Rommel’s armour. Only the thinness of the pursuing force saved them from being trapped and ‘put in the bag’ before they got back into the shelter of the Alamein line.

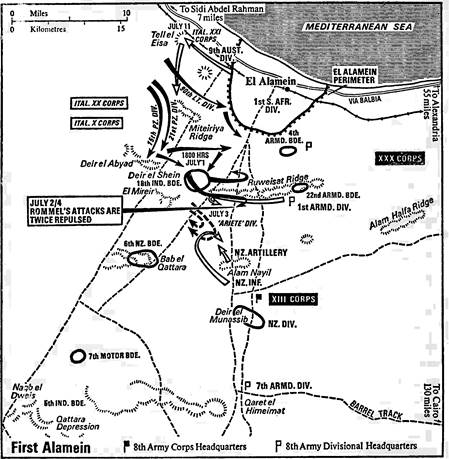

Rommel’s momentary pause may have been caused by mistaken Intelligence reports about the strength of that defensive position. Actually, it comprised four ‘boxes’, which had been laid out in the thirty-five-mile stretch between the coast and the steep drop into the great Qattara Depression — which, because of the salt marsh and soft sand, limited an outflanking move. The largest and strongest ‘box’ lay on the coast at Alamein, and was occupied by the 1st South African Division. The next, similar, to the south, was a newly-made one at Deir el Shein, occupied by the 18th Indian Brigade. The third, seven miles beyond, was the Bab el Qattara Box (called by the Germans Qaret el Abd) which was occupied by the 6th New Zealand Brigade. Then, after a fourteen mile gap, came the Naqb el Dweis Box held by a brigade of the 5th Indian Division. The intervals were covered by a chain of small mobile columns formed from these three divisions and remnants of the two that had garrisoned Mersa Matruh.

In making his plan of attack, for July 1, Rommel did not know of the existence of the new ‘box’ at Deir el Shein. Nor did he know that the British armour had been outstripped in its retreat by his advance, and was only just arriving back at Alamein. So he reckoned that it would probably be posted in the south to cover that flank. On this reckoning, he planned a pinning attack there, followed by a quick switch northward of the Afrika Korps for a breakthrough thrust in the stretch between Alamein and Bab el Qattara. But the Afrika Korps ran into the ‘unknown’ Deir el Shein Box, and was held up until the evening before it succeeded in capturing the ‘box’, with most of its defenders. But they had held out long enough to annul Rommel’s hope of a quick breakthrough and its swift exploitation. The British armour arrived on the scene too late to save the ‘box’, but its belated appearance helped to check the Afrika Korps from continuing the advance. Rommel ordered it to push on by moonlight, but that intention was frustrated by the British aircraft which utilised the moonlight to bomb and disperse the German supply columns.

This day — Wednesday, July 1 — was the most dangerous moment of the struggle in Africa. It was more truly the turning point than the repulse of Rommel’s renewed attack at the end of August or the October battle that ended in Rommel’s retreat — the battle which, because of its more obviously dramatic outcome, has come to monopolise the name of ‘Alamein’. Actually, there was a series of ‘Battles of Alamein’, and the ‘First Alamein’ was the most crucial.

The news that Rommel had reached Alamein had led the British fleet to leave Alexandria, and withdraw through the Suez Canal into the Red Sea. Clouds of smoke rose from the chimneys of the military headquarters in Cairo as their files were hastily burned. In grim humour, soldiers called it ‘Ash Wednesday’. Veterans of World War I remembered that it was the anniversary of the opening day of the Somme offensive in 1916, when the British Army lost 60,000 men — the worst day’s loss in all its history. Seeing the black snowstorm of charred paper, the people of Cairo naturally took it as a sign that the British were fleeing from Egypt, and crowds besieged the railway station in a rush to get away. The world outside, on hearing the news, took it to mean that Britain had lost the war in the Middle East.

But by nightfall the situation at the front had become hopeful, and the defenders more confident — in contrast to the state of panic at the back of the front.

Rommel continued his attack on July 2, but the Afrika Korps had less than forty tanks left fit for action and the troops were dead-tired. Its renewed attack did not get going until the afternoon, and soon came to a halt on sighting two larger bodies of British tanks — one in its path and the other moving round its flank. Auchinleck had coolly gauged the situation, realised the weakness of Rommel’s attacking forces, and planned what he hoped would prove a decisive counterstroke. His plan was not carried out as intended, and the hitches in execution frustrated his hopes, but it served to foil Rommel’s aim.

Rommel made a further effort on July 3, but by then the Afrika Korps had only twenty-six tanks fit for action, and its eastward push that morning was checked by the British armour, although a renewed effort in the afternoon advanced nine miles before it was halted. A converging advance by the Ariete Division was also repelled, and during the action a New Zealand battalion, the 19th, captured almost the whole of the Ariete’s artillery in a sudden counterattack on its flank — and ‘the remainder took to their heels in panic’,* That collapse was a clear sign of overstrain.

*

The Rommel Papers,

p. 249.

Next day, July 4, Rommel ruefully wrote home: ‘Things are, unfortunately, not going as we should like. The resistance is too great, and our strength is exhausted,’ His thrusts had not only been parried but answered by upsetting ripostes. His troops were too tired as well as too few to be capable of making a fresh effort for the moment. He was forced to break off the attack and give them a breather, even though it meant giving Auchinleck time to bring up reinforcements.

Moreover Auchinleck had regained the initiative, and he came close to turning the tables decisively even before reinforcements arrived. His plan that day was broadly the same as on the previous day — to hold the Panzerarmee’s attack in check with Nome’s 30th Corps, while Gott’s 13th Corps in the south struck upward across the enemy’s rear. But this time the bulk of the armour was kept in the north under the 30th Corps, although the 13th Corps included the recently reorganised 7th Armoured Division, now called a ‘light armoured division’ and composed of a motor brigade, armoured-cars, and Stuart tanks. It lacked punch, but had the mobility for a quick and wide drive round the enemy’s rear while the strong New Zealand Division attacked his flank.