History of the Second World War (74 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

By 9.30 a.m. the 4th Indian Division had punched a deep hole, at a cost of little more than a hundred casualties, and reported that there was no sign of any serious opposition ahead — telling Corps Headquarters that the armour could now ‘go as fast and as far as it liked’. Before 10 a.m. the leading troops of the 7th Armoured Division had begun to pour through the line gained by the infantry. On the right wing, the British 4th Division was late in starting and slower in advancing, but was helped by the thrust of its left wing neighbour, and reached its objective before noon. The armoured divisions were then at last permitted to drive on. In mid-afternoon, however, they were halted for the night near Massicault — which was barely six miles beyond the start-line of the assault and three miles beyond the line gained by the infantry, while only a quarter of the way to Tunis. This extreme caution is explained in the divisional history of the 7th by the statement that the commander ‘considered that it would be wiser to keep each Brigade in the firm positions they both held rather than to loosen the hold of both and complicate the long task of replenishment’ — an explanation which shows all too clearly a failure to grasp the elementary principles of exploitation, and to fulfil its spirit. As at Wadi Akarit, Horrocks and the commanders of the armoured divisions were slow to respond to the call of opportunity, and continued to operate at a tempo more characteristic of infantry action than fitted to fulfil the potentialities of mechanised mobility.

There was no need for such caution. The eight-mile sector south of the Medjerda River where the blow was struck, on a two-mile frontage, had been held by two weak infantry battalions and an anti-tank battalion of the 15th Panzer Division, supported by a composite force of less than sixty tanks — almost all that remained of the Axis armour. This very thin shield had been stunned and pulverised by the tremendous concentration of shells and bombs supporting the assault. Moreover lack of fuel had prevented Arnim from bringing northward the unarmoured remainder of the 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions, as had been planned. That fatal lack of fuel had proved more effective in pinning them down than the elaborate deception plan which the British had designed to make it appear that they were again going to strike in the Kourzia sector.

The 6th and 7th Armoured Divisions resumed their advance at dawn, on May 7, but again showed excessive caution, and were held up until the afternoon by a handful of Germans, with ten tanks and a few guns, at St Cyprien. It was 3.15 p.m. before the order was given to drive into Tunis. The armoured-cars of the 11th Hussars entered the city half an hour later, and thus fittingly crowned the leading role this regiment had played since the start of the North African campaign nearly three years earlier. The Derbyshire Yeomanry, the armoured-car regiment of the 6th Armoured Division, entered almost simultaneously. They were followed up by tanks and motor-borne infantry to extend and complete the occupation of the city. In the process, the troops suffered more embarrassment and obstruction from the hysterical enthusiasm of the population, pelting them with flowers and kisses, than from the sporadic resistance put up by small pockets of confused and disorganised Germans. A considerable number were taken prisoner that evening, and many more were rounded up next morning, while a much larger proportion sought to escape by fleeing northward or southward from the city. What remained of the fighting formations on the perimeter also retreated in these divergent directions once they were split asunder by the thrust into Tunis.

Meanwhile the U.S. 2nd Corps had resumed its attack in the northern sector to coincide with the British thrust. Progress on May 6 had been slow, and resistance seemed still stiff, but on the next afternoon reconnaissance elements of the 9th Infantry Division found the road open and drove into Bizerta at 4.15 p.m., the enemy having evacuated the city and withdrawn south-eastward. Formal entry into the city was reserved for the French Corps Franc d’Afrique, which arrived on the 8th. The 1st Armored Division, advancing from Mateur, had suffered checks on the first two days. So had the 1st and 34th Infantry Divisions farther south. But on the 8th the 1st Armored found the defence collapsing and progress easy, as the enemy’s ammunition and fuel became exhausted and the British 7th Armoured Division were swinging north from Tunis along the coast in his rear.

Trapped between the British and American spearheads, and without means of resistance or retreat, mass surrenders began. The leading squadron of the 11th Hussars had some 10,000 prisoners on its hands before evening. Early next morning, the 9th, part of another squadron drove on to Porto Farina, near the cape of that name twenty miles east of Bizerta, where it received the surrender of 9,000 more who were crowded on the beach, some of them pathetically trying to build rafts — and were relieved to be able to hand this crowd of prisoners over to the American armoured force which arrived soon afterwards. At 9.30 a.m. General von Vaerst, commanding the 5th Panzer Army and the northern area, signalled to Arnim: ‘Our armour and artillery have been destroyed. Without ammunition and fuel. We shall fight to the last.’ The final sentence was a gallant bit of absurdity, for troops cannot fight without ammunition. Vaerst soon learnt that his troops, realising how nonsensical were such heroic orders, were giving themselves up. So by midday, he agreed to a formal surrender of his remaining troops, which raised the total bag in this area to nearly 40,000.

A much larger part of the Axis forces, when the split was produced, lay in the area south of Tunis. This area was also more defensible by nature, and the Allied commanders expected that the enemy would make a more prolonged stand there. But there, too, the exhaustion of the enemy’s ammunition and fuel produced a quick collapse after a short resistance. The collapse was accelerated by a general feeling of hopelessness, since even where some supplies remained the Axis troops were aware that no replenishments were possible — for the same reason that no escape was possible.

Alexander’s aim now was to prevent Messe’s army, the southerly part of the Axis forces, retreating into the large Cap Bon peninsula and establishing a firm ‘last ditch’ position there. So the 6th Armoured Division, as soon as Tunis had been captured, was ordered to turn south-east and drive for Hamman Lif, the near corner of the peninsula’s baseline, while the 1st Armored Division converged in the same direction. At Hamman Lif the hills came so close to the sea that the flat coastal strip was only 300 yards wide. This narrow defile was held by a German detachment, supported by 88-mm. guns withdrawn from airfield defence, and for two days it blocked all efforts to force a passage. But the obstacle was eventually overcome by a well-combined effort. The infantry of the 6th Armoured Division captured the heights overlooking the town, the artillery swept the streets methodically block by block, and a column of tanks was then sent along the beach at the edge of the surf, where they were better shielded from the fire of the one German gun that remained in action. By nightfall on the 10th the drive was extended across the baseline of the peninsula to Hammamet, thus cutting off the enemy’s surviving forces. Paralysed by lack of fuel, they had been unable to withdraw to the peninsula. Next day the 6th Armoured Division drove on southward into the rear of the Axis troops who were keeping the British Eighth Army in check near Enfidaville. Although these still had some ammunition in hand, the definite proof that they were trapped and without hope of escape produced their speedy surrender.

By the 13th all the remaining Axis commanders and their troops had submitted. Only a few hundred had escaped by sea or air to Sicily — beyond the 9,000 wounded and sick who had been evacuated since the beginning of April. As to the size of the final bag, there is a lack of certainty. On May 12 Alexander’s headquarters reported to Eisenhower that the number of prisoners since May 5 had risen to 100,000 and it was reckoned as likely to reach 130,000 when the count was complete. A later report ‘gave the total bag at about 150,000’. But in his post-war Despatch Alexander said that the total was ‘a quarter of a million men’. Churchill in his Memoirs gives the same round figure, but qualifies it with the word ‘nearly’, Eisenhower gives it as ‘240,000, of which approximately 125,000 were Germans’. But Army Group Afrika had reported to Rome on May 2 that its ration strength during the month of April had varied between 170,000 and 180,000 — and that was before the heavy fighting in the last week of the campaign. So it is hard to see how the number of prisoners taken could have exceeded this strength by nearly 50 per cent. Administrative staffs who are responsible for feeding troops do not tend to underestimate their numbers. Here it is worth remark that much larger discrepancies still, between the last known German ration strength and the Allied claims about the number of prisoners captured, were manifest in the final stages of the war.

But whatever may have been the exact number taken in Tunisia it was certainly a very large bag. The most important effect was that it deprived the Axis of the bulk of its battle-tested troops in the Mediterranean theatre which could otherwise have been used to block the Allies’ coming invasion of Sicily — the first and crucial phase of their re-entry into Europe.

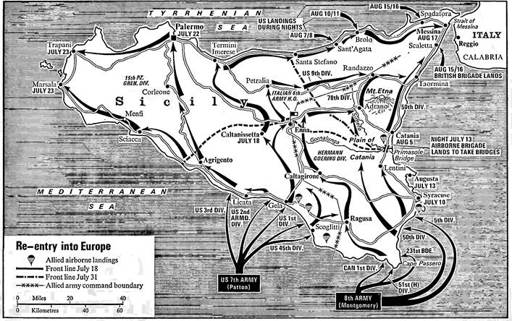

CHAPTER 26 - RE-ENTRY INTO EUROPE — THROUGH SICILY

After the event, the Allies’ conquest of Sicily in 1943 looked an easy matter. But actually this initial re-entry into Europe was a hazardous leap, hedged with uncertainties. For its successful outcome it owed much to a series of long-hidden factors. First to the blind pride of Hitler and Mussolini jointly in trying to ‘save face’ in Africa. Then to Mussolini’s jealous fear of his German allies, and reluctance to let them take a leading part in the defence of Italian territory. Then to Hitler’s belief, in disagreement with Mussolini, that Sicily was not the Allies’ real objective — a mistaken belief that partly arose from a brilliantly subtle ruse ‘planted’ by the British deception plan.

The first factor counted most of all. One of the greatest ironies in the whole war was the way that Hitler and the German General Staff — who had always feared to embark on overseas expeditions in reach of British seapower — abstained from sending Rommel sufficient forces to follow up his victories, yet in the last lap sent so many troops across to Africa as to forfeit their prospects of defending Europe.

Ironically, too, they were drawn into this fatal folly by their own unexpected success in halting Eisenhower’s first drive for Tunis after they had been caught napping by the Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa in the previous November. While the Allies’ spearhead was advancing rather cautiously eastward from Algeria, the Germans had quickly reacted to the threat by starting to fly troops across the Mediterranean in the hope of frustrating the Allies’ early capture of the ports of Tunis and Bizerta. They succeeded in holding the mountain approaches and producing a prolonged stalemate.

But the success of this forestalling move encouraged Hitler and Mussolini to believe that they could hold on to Tunisia indefinitely. So they decided to pour in reinforcements on a large enough scale to match Eisenhower’s growing strength. The more their commitment increased, the more they felt that they could not withdraw without losing prestige. At the same time the difficulty either of withdrawing or of holding on increased as the Allies’ superior naval and air forces began to develop a stranglehold on the straits between Sicily and Tunisia.

The German-Italian bridgehead that was built up in Tunisia kept the Allies at bay throughout the winter, and provided shelter for the remains of Rommel’s army at the end of his 2,000-mile retreat from Alamein. Nevertheless, the Allies’ early failure to capture Tunisia turned out immensely to their advantage in the long run. For Hitler and Mussolini would not listen to any argument for evacuating the German and Italian troops while there was still time and opportunity to get them away.

In a final effort to convince Hitler of the necessity, Rommel flew to Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia on March 10, 1943. His journal records how futile it proved: ‘I emphasised as strongly as I could that the “African” troops must be re-equipped in Italy to enable them to defend our southern European flank. I even went so far as to give him a guarantee — something which I am normally very reluctant to do — that with these troops, I would beat off any Allied invasion in southern Europe. But it was all hopeless.’*

*

The Rommel Papers,

p. 419.

As the Allied armies closed in upon the bridgehead ‘for the kill’, the Axis troops had to sit there with sinking spirits, awaiting the blow — and foregoing the chance provided by a spell of misty weather in April that would have helped to screen their embarkation and transportation if they had been allowed to withdraw. They managed to check the Allies’ first attempt to crack their defence, April 20-22, but collapsed when their front was penetrated in the next big attack, on May 6

.

The complete breakdown that followed was largely due to the shallowness of the bridgehead and the defending troops’ acute consciousness that they were fighting with their backs close to a hostile sea.