History of the Second World War (77 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

no use was made by the 8th Army of amphibious opportunities. The small L.S.I.s were kept standing by for the purpose . . . and landing craft were available on call. . . . There were doubtless sound military reasons for making no use of this, what to me appeared, priceless asset of sea power and flexibility of manoeuvre: but it is worth consideration for future occasions whether much time and costly fighting could not be saved by even minor flank moves which must necessarily be unsettling to the enemy.

Much to Kesselring’s relief, the Allied High Command had not attempted a landing in Calabria, the ‘toe’ of Italy, behind the back of his forces from Sicily — to block their withdrawal across the Straits of Messina. He had been anxiously expecting such a stroke throughout the Sicilian campaign, while having no forces available to meet it. In his view, ‘a secondary attack on Calabria would have enabled the Sicily landing to be developed into an overwhelming Allied victory’. Until the close of the Sicilian campaign and the successful escape of the four German divisions engaged there, Kesselring had only two German divisions to cover the whole of southern Italy.*

* Cunningham:

Despatch,

p. 2082.

CHAPTER 27 - THE INVASION OF ITALY — CAPITULATION AND CHECK

‘Nothing succeeds like success’ is a very well-known saying, based on an old French proverb. But it often proves true, in a deeper sense, that ‘nothing succeeds like failure’. Religious and political movements which reigning authority crushed have frequently been revived and come out on top in the long run after their leaders gained the halo of martyrdom. The crucified Christ became more potent than the living one. Conquering generals have been eclipsed by the conquered — that is shown by the immortal fame of Hannibal, Napoleon, Robert E. Lee, and Rommel.

In the history of nations the same effect can be seen, though in a subtler way. Everyone knows the saying that in a war ‘the British only win one battle — the last’. It expresses their characteristic tendency to start with disasters but end with victory. The habit is hazardous, and costly. Yet it happens, ironically, that the final outcome can often be traced to the initial way that the early defeats suffered by the British and their allies, by making the enemy overconfident, have led him to overreach himself.

Moreover, even when the scales have turned, a failure to gain immediate success has at times turned out very advantageously by helping towards fuller success and making final success more sure. That happened twice, most strikingly, in the Mediterranean campaigns of the Second World War.

It was due to the frustration of the Allies’ original advance on Tunis, from Algiers, in November 1942, that Hitler and Mussolini were encouraged to send a stream of reinforcements there, across the sea, where the Allies were eventually able to trap them six months later and put two Axis armies in the bag — thus removing the chief obstacle to their own cross-sea jump from Africa into Southern Europe.

The next case of a miscarriage turning out well was the invasion of Italy itself. After the swift capture of Sicily, and the downfall of Mussolini, the second and shorter jump into Italy had looked a comparatively easy matter. The prospects were all the brighter because Italy’s surrender had been secretly arranged, unknown to the Germans, and was timed for announcement simultaneously with the main Allied landing. At that moment there were only six weak German divisions in the south of Italy, and two divisions near Rome, to cope with the double burden of meeting the Allied invasion and at the same time holding down their own Italian ex-allies.

Field-Marshal Kesselring, however, managed to keep the invaders in check while disarming the Italians, and then brought the Allied armies to a standstill on a line a hundred miles short of Rome. Eight months passed before the Allies succeeded in reaching the Italian capital, and then they were again held up — for a further eight months — before they could break out of the narrow and mountainous peninsula into the plains of northern Italy.

Yet that long postponement, of the end that had seemed so close in September 1943, carried important compensations for the Allies’ prospects in general. Hitler had at first intended to extricate his forces from southern Italy, and establish a mountain blocking-line in the north, But Kesselring’s unexpectedly successful defence induced Hitler, contrary to Rommel’s advice, to pour resources southward with the aim of holding on to as much of Italy as possible, and for as long as possible. That decision was taken at the expense of the resources which Hitler soon needed to meet the more dangerous menace of the two-sided advance on Germany by the Russians from the East and by the Western Allies from Normandy.

Relative to its own strength, the Allied force in Italy absorbed a higher proportion of the Germans’ resources than those on other fronts. Moreover, the Italian front was the one where the Germans could afford to yield ground with least risk, while the more they strained their strength to hold an extended front on every side, the more liable they became to a fatal collapse through over-stretch. Such reflections helped to console the Allied troops in Italy, under Alexander, for the prolonged frustration of their own hopes of early victory.

Even so, it should be realised that great expeditions are not launched in the hope of reaching a frustration that may ultimately become profitable. It is not in human nature to desire and seek a failure. So it is worthwhile to explore what happened and the way it did.

The first important factor in the Allies’ frustration was their delay in exploiting the opportunity offered by the anti-war coup d’etat in Italy which overthrew Mussolini. This took place on July 25, yet more than six weeks passed before the Allies moved into Italy. The causes of delay were both military and political. At the conference of the Anglo-American service chiefs in Washington at the end of May, the Americans had opposed the idea of going on from Sicily to Italy, lest such a step might interfere with the plans for invading Normandy and defeating the Japanese in the Pacific. It was not until July 20, when the Italian forces in Sicily had shown their eagerness to surrender, that the American Chiefs of Staff agreed to a follow-up advance into Italy. But that was too late for making ready an immediate follow-up.

The political demand for ‘unconditional surrender’, formulated by President Roosevelt and Mr Churchill at the Casablanca Conference in January, was also a hindrance. The new Italian Government under Marshal Badoglio was naturally anxious to see if more favourable conditions could be obtained in negotiation with the Allied Governments but found that it was difficult to get in touch with them. The British and American Ministers at the Vatican were an obvious channel, and easily accessible, but proved useless owing to an extraordinary double case of official short-sightedness, as Badoglio’s account reveals. ‘The British Minister informed us that unfortunately his secret code was very old and almost certainly known to the Germans, and that he could not advise us to use it for a secret communication to his Government. The American charge d’affaires replied that he had not got a secret code.’ So the Italians had to wait until in mid-August they found a plausible pretext for sending an envoy on a visit to Portugal, where he could meet British and American representatives. Even then this roundabout way of negotiation entailed further delay in settling the matter.

Hitler, by contrast, had wasted no time in taking steps to counter the likelihood that the new Italian Government would seek peace and abandon the alliance with Germany. On the day of the coup d’etat in Rome, July 25, Rommel had arrived in Greece to take command there, but just before midnight he received a telephone call telling him that Mussolini had been deposed, and that he was to fly back at once to Hitler’s headquarters in the East Prussian forests. Arriving there at noon next day he ‘received orders to assemble troops in the Alps and prepare a possible entry into Italy’.

The entry soon began, in a partially disguised way. Fearing that the Italians might make a sudden move to block the Alpine passes with the help of Allied parachute troops, Rommel gave orders on July 30 for the leading Germans to move across the frontier and occupy the passes. This was done under the excuse of safeguarding the supply routes into Italy against sabotage, or paratroop attack. The Italians protested, and for a moment threatened to resist the passage, but hesitated to open fire and precipitate a conflict with their allies. The German infiltration was then extended on the pretext of relieving the Italians of the burden of defending the northern part of their country so that they could reinforce the south, where it was manifest that the Allies were likely to land at any moment. Strategically, this argument was so reasonable that the Italian chiefs could hardly reject it without showing their own intention to change sides. So by the beginning of September eight German divisions under Rommel were established inside Italy’s Alpine frontier-wall as a potential support or reinforcement to Kesselring’s forces in the south.

Moreover the 2nd Parachute Division, a particularly tough force, was flown from France to Ostia, close to Rome. General Student, the Commander-in-chief of the German airborne forces, went with it. When interrogated after the war, he said:

The Italian High Command was given no previous warning of its arrival, and was told that the division was intended for the reinforcement of Sicily or Calabria. But my instructions, from Hitler, were that I was to keep it near Rome, and also take under my command the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, which had moved down there. With these two divisions I was to be ready to disarm the Italian forces around Rome.*

* Liddell Hart interrogation.

See also

Liddell Hart;

The other Side of the Hill

, pp. 356-7.

The presence of these divisions nullified the Allies’ plan to drop one of their own airborne divisions, the 82nd American (General Matthew Ridgway), on Rome itself to support the Italians in holding the capital. If that reinforcement had come, Kesselring’s own headquarters would have been in jeopardy, for it was located at Frascati, barely ten miles south-east of Rome.

Even so, Student’s allotted task looked a very difficult one — before the event. Marshal Badoglio had kept five Italian divisions concentrated in the Rome area despite the Germans’ efforts to persuade him to send some of these divisions to help in defending the coast in the south. Unless and until they could be disarmed Kesselring would be in the awkward situation of having to face two Anglo-American invading armies with a third hostile army already lying astride the line of supply and retreat of his six German divisions in southern Italy. These had just been formed into what was called the 10th Army, commanded by Vietinghoff, and included four divisions which had escaped from Sicily, badly depleted by the losses they had suffered in that campaign.

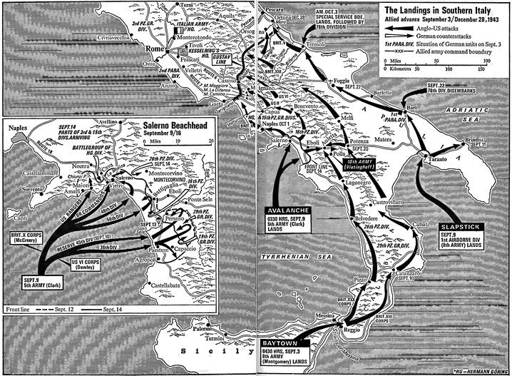

On September 3, the invasion was opened by Montgomery’s Eighth Army crossing the narrow Straits of Messina, from Sicily, and landing on the toe of Italy. That same day the Italian representatives secretly signed the armistice treaty with the Allies. But it was arranged that the fact should be kept quiet until the Allies made their second and principal landing — which was planned to take place on the shin of Italy, at Salerno, south of Naples.

At midnight on September 8 the Anglo-American Fifth Army under General Mark Clark began to disembark in the Gulf of Salerno — a few hours after the B.B.C. had broadcast the official announcement of Italy’s capitulation. The Italian leaders had not been expecting the landing to come so soon, and they were warned about the delivery of the broadcast only late in the afternoon. Badoglio complained, with some justification, that he was caught unready to co-operate, before his preparations were complete. But the Italians’ state of unreadiness and trepidation had already become so evident to General Maxwell Taylor, who had been sent to Rome secretly by Eisenhower, that Ridgway’s intended airborne descent on Rome had been cancelled after Eisenhower had received that morning a warning message from Taylor that the prospects were poor. It was then too late to revert to the original plan of dropping Ridgway’s troops along the Volturno River, on the north side of Naples, to block enemy reinforcements from moving southward, to Salerno.

The broadcast announcement of the Italian capitulation also took the Germans by surprise, but their action in Rome was prompt and decisive, despite the simultaneous emergency in the south produced by the landing at Salerno.

The outcome might well have been different if Italian action had matched Italian acting, which had gone a long way to conceal intentions and lull Kesselring’s suspicions during the preceding days. A piquant account of this is given in a narrative written by his Chief of Staff, General Westphal:

On September 7 the Italian Minister of Marine, Admiral Count de Courten, called on Field-Marshal Kesselring to inform him that the Italian Fleet would put out on the 8th or 9th from Spezia to seek battle with the British Mediterranean Fleet. The Italian Fleet would conquer or perish, he said, with tears in his eyes. He then described in detail its intended plan of battle.*