Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (106 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

It was a historic document. The great moment had come. The Army was to assemble for its march into freedom. For the moment, however, only "Winter Storm" was in force—

i.e.,

a corridor was to be cleared to Hoth's divisions, but Stalingrad was not to be evacuated for the time being.During the afternoon Manstein had again tried to obtain Hitler's consent to an immediate total break-out by Sixth Army, to Operation "Thunder-clap." But Hitler only approved "Winter Storm," while refusing his consent to the major solution. Nevertheless Manstein, as this document reveals, issued orders to Sixth Army to prepare for "Thunder-clap," and explicitly stated under (3): "Development of the situation may make it imperative to extend instruction for Army to break through." To extend it, that is, into a break-out.

The drama had reached its climax. The fate of a quarter million troops depended on two code names—"Winter Storm" and "Thunder-clap."

At 2030 hours the two chiefs of staff were again sitting in front of their teleprinters. General Schmidt reported that enemy attacks were engaging the bulk of Sixth Army's tanks and part of its infantry strength. Schmidt added: "Only when these forces have ceased to be tied down in defensive fighting can a break-out be launched. Earliest date 22nd December." That was three days ahead.

It was an icy night. In the bunkers at Gumrak there was feverish activity. On the following morning at 0700 hours Paulus was already on his way to the crisis points of the pocket. Throughout the day there was local fighting in many sectors. In the afternoon, when the two chiefs of staff, Schultz and Schmidt, had another conversation over the teleprinters, Schmidt reported: "As a result of losses during the past few days manpower situation on the western front and in Stalingrad exceedingly tight. Penetrations can be cleared up only by drawing upon the forces earmarked for 'Winter Storm.' In the event of major penetrations, let alone breakthroughs, our Army reserves, in particular the tanks, have to be employed if the fortress is to be held at all. The situation could be viewed somewhat differently," Schmidt added, "if it were certain that 'Winter Storm' will be followed immediately by 'Thunderclap.' In that event local penetrations on the remaining fronts could be accepted provided they did not jeopardize the withdrawal of the Army as a whole. In that event we could be considerably stronger for a break-out towards the south, as we could then concentrate in the south numerous local reserves from all fronts."

It was a vicious circle, a problem that could be solved only if permission for "Thunder-clap" was obtained.

General Schultz replied, unfortunately through the medium of the teleprinter so that the imploring note in his voice was lost, as he dictated to his clerk: "Dear Schmidt, the Field-Marshal believes that Sixth Army must launch 'Winter Storm' as soon as possible. You cannot wait until Hoth has got to Buzinovka. We fully realize that your attacking strength for 'Winter Storm' will be limited. That is why the Field-Marshal is trying to get approval for 'Thunder-clap.' The struggle for this approval has not yet been decided at Army High Command in spite of our continuous urging. But regardless of the decision on 'Thunder-clap' the Field-Marshal emphatically points out that 'Winter Storm' must be started as soon as possible. As for fuel supplies, food-stuffs, and ammunition, over 3000 tons of stores loaded on columns are already standing behind Hoth's Army and will be ferried through to you the moment the link-up has been established. Together with this cargo column numerous towing vehicles will be sent to you in order to make your artillery mobile. Moreover, thirty buses are standing by to evacuate your wounded."

Thirty buses! Nothing, evidently, had been forgotten. And all that stood between Sixth Army and salvation was 30 miles as the crow flew, or 40 to 45 miles by road.

At that moment, right in the middle of these considerations and calculations, planning and preparations, a new disaster befell the German front in the East: three Soviet Armies had launched an attack against the Italian Eighth Army on the middle Don on 16th December. Once again the Russians had chosen a sector held by the weak troops of one of Germany's allies.

After short savage fighting the Soviets broke through. The Italians fled. The Russians raced on to the south. One Tank Army and two Guards Armies flung themselves against the laboriously established weak German line along the Chir. If the Russians succeeded in overrunning the German front on the Chir there would be nothing to halt them all the way to Rostov. And if the Russians took Rostov, then Manstein's Army Group Don would be cut off and von Kleist's Army Group in the Caucasus would be severed from its rearward communications. It would be a super-Stalingrad. What would be at stake then was no longer the fate of 200,000 to 300,000 men, but a million and a half.

On 23rd December, while the men of Sixth Army were still hopefully awaiting their liberators, enemy armoured spearheads were already striking down from the north towards the airfield of Morozovsk, 95 miles west of Stalingrad, on which the surrounded Army's entire supplies depended. The disastrous situation was thus plain. Hollidt's group on the Chir no longer had any flank cover.

In this situation Manstein had no other choice than to order Hoth to switch one of his three Panzer divisions immediately to the left, to the lower Chir, in order to forestall a further breakthrough by the Russians. Hoth did not hesitate, and made his strongest unit available for this vital task.

The 6th Panzer Division was in the middle of its attack in the direction of Stalingrad when the order to turn away reached it. Left with only two battle-weary divisions, Hoth now found it impossible to continue his attack towards Stalingrad. Indeed, under pressure from the Soviet Second Guards Army, he even had to withdraw behind the Aksay on Christmas Eve.

Field-Marshal von Manstein was a very worried man. He sent an urgent teleprinter signal to the Fuehrer's Headquarters, imploring him:

The turn taken by the situation on the left wing of the Army Group requires the immediate switching of forces to that spot. This measure means dropping for an indefinite period the relief of Sixth Army, which in turn means that this Army would now have to be adequately supplied on a long-term basis. In Richthofen's opinion no more than a daily average of 200 tons can be counted on. Unless adequate aerial supplies can be ensured for Sixth Army the only remaining alternative is the earliest possible breakout of Sixth Army at the cost of a considerable risk along the left wing of Army Group. The risks involved in this operation, in view of that Army's condition, are sufficiently known.

In military officialese this message said all there was to be said: Sixth Army must now break out or else it is lost.

Tensely the reply was awaited at Novocherkassk. Zeitzler sent it by teleprinter: The Fuehrer authorizes the withdrawal of forces from Army Group Hoth to the Chir, but he orders that Hoth should hold his starting-lines in order to resume

his relief attack as soon as possible.

It was beyond comprehension. Admittedly, Hitler had a cogent argument against authorizing "Thunder-clap": Paulus, he argued, did not have enough fuel to get through to Hoth. This view was based on a report by Sixth Army to the effect that the tanks had enough fuel left only for a fighting distance of 12 miles. This report has since been frequently questioned, but General Schmidt has recalled his strict controls designed to establish stocks of 'black' petrol, and Paulus himself has pointed out, and justly so, that no Army could base a life-and-death operation on the suspected existence of 'black' petrol supplies.

Faced with this situation, Manstein once more had himself put through to Paulus by teleprinter in the afternoon of 23rd December, and asked him to examine whether "Thunderclap" could not after all be carried out if no other choice was left.

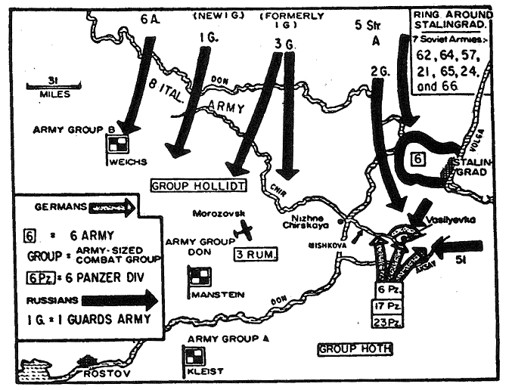

Map 36.

On 22nd December 1942 the armoured spearheads of Hoth's Army-size combat group were within 30 miles of the Soviet ring around Stalingrad. However, the Russian breakthrough in the sector held by the Italian Eighth Army prevented the continuation of the relief offensive. As the Russian thrust was aimed at Rostov, threatening both Manstein's and Kleist's Army Groups with encirclement, Sixth Army had to be sacrificed in order to avert this greater danger.Paulus asked: "Does this conversation mean that I have authority to initiate 'Thunder-clap'?"

Manstein: "I cannot give you this authority to-day, but am hoping for a decision to-morrow." The Field-Marshal added: "The point at issue is whether you trust your Army to fight its way through to Hoth if long-term supplies cannot be laid on for you."

Paulus: "In that case we have no other alternative." Manstein: "How much fuel do you need?"

Paulus: "One thousand cubic metres."

But a thousand cubic metres meant about a quarter of a million gallons or a thousand tons.

Why, one might ask, did Paulus not mount his operation at that moment in spite of all risks and all of his misgivings? Why did he not comply with the order to launch "Winter Storm"—regardless of fuel supplies and foodstuffs, considering that in any case the survival of the Army was at stake?

In his memoirs Field-Marshal von Manstein outlines the responsibility which that order placed on Paulus. The three divisions in the south-western corner of the pocket, where the break-out was to be made, were extensively involved in defensive fighting. Could Paulus run the risk of launching his attack with only parts of these divisions, in the hope of bursting through the powerful ring of encirclement? Besides, would the Soviet attacks even give him a chance of doing so? And would he be able to hold the remaining fronts until Army Group issued the command "Thunder-clap," thus authorizing him to launch the full-scale break-out? And would the tanks have enough fuel to get back again into the pocket in the event of "Winter Storm" being a failure? And what would become of the 6000 wounded and sick?

Paulus and Schmidt could see only the possibility of launching "Winter Storm" and "Thunder-clap" simultaneously. And even that would be practicable only after sufficient quantities of fuel had been flown in.

Army Group, on the other hand, wanted to initiate the full-scale break-out by "Winter Storm" alone, taking the view that the Soviet ring must first be breached along the south-western front before the separate sectors of the pocket front could be dismembered one by one—in other words, before "Thunderclap" could be set in motion.

Quite apart from military considerations, Manstein's schedule was based on the conviction that only such a phased evacuation would lead Hitler to accept the inevitability of the abandonment of Stalingrad; only then would he be unable to countermand it. Field-Marshal von Manstein knew very well that if Army Group were to order Sixth Army from the outset to launch its full-scale break-out and abandon Stalingrad this order would undoubtedly be countermanded by Hitler without delay.

Paulus, however, tied down in his pocket and fully engaged with improvisations against Soviet attacks, was unable at the time to see the overall picture.

Clearly there is nothing to be gained from seeking the causes of the Stalingrad tragedy at the level of Sixth Army or of Army Group Don, or by trying to pin responsibility on any individual in the sector.

Hitler's strategic mistakes, based as they were on underrating the enemy and overrating his own forces, had brought about a situation which could no longer be remedied by makeshift expedients, ruses of war, or hold-on orders. Only the timely withdrawal of Sixth Army in October could have averted the catastrophe which befell a quarter-million troops on the Volga. Admittedly, even that would no longer have changed the outcome of the war.

To-day, moreover, it is clear from what we know about Russian strength, as revealed by Soviet military writers, that even "Winter Storm" and "Thunder-clap" would no longer have saved a combat-worthy Army. But there might possibly have been a hope of saving the bulk of the men in the Stalingrad pocket. When Horn's relief attack had to be called off about Christmas even that hope was lost.

The sector of 2nd Battalion, 64th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, contained something unusual—a snow-covered wheat- field with the ears of grain just about showing above the snow. At night the men would crawl out on their bellies, cut off the wheat-ears, and, then back in their dug-outs, would shake out the grams and boil them with water and horse- flesh to make soup. The horse-flesh was that of their animals, which had either been killed in action or died a natural death and were now lying all over the countryside, frozen rigid under small mounds of snow.

Other books

The Torch of Tangier by Aileen G. Baron

Breaking the Silence by Diane Chamberlain

On Black Sisters Street by Chika Unigwe

Rude Astronauts by Allen Steele

Faces of Evil [2] Impulse by Debra Webb

Sacrifice Me: The Darkness (Episode 3) by Sarra Cannon

Rosetta by Alexandra Joel

Night Music by Jojo Moyes

Will of Man - Part Two by William Scanlan