Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (49 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

As though in confirmation, rifle-fire broke out near by. Alarm! The Russians are here!

The Soviets evidently had got wind of the relief by Rumanian formations. With newly brought up forces of their Ninth and Eighteenth Army they attacked the covering lines of the Eleventh Army just as it was regrouping. Some units of the Rumanian Third Army retreated at once. The Russians pressed on, put the entire 4th Brigade to flight, and tore a nine-mile gap in the front. Faced with this situation, Man-stein was compelled to recall his Mountain Corps again and employ it at the penetration point.

To complete the disaster, the Soviets also achieved a breakthrough on the southern wing, at General von Salmuth's XXX Corps. A break-through in the sector of the Rumanian 5th Cavalry Brigade was sealed off by the combat group von Choltitz with units of 22nd Infantry Division, and the front propped up again. After that followed a penetration on the Corps' northern wing. The Rumanian 6th Cavalry Brigade retired. In order to clear up this new crisis the 170th Infantry Division, placed under the Mountain Corps, had to be stopped and the "Leibstandarte," which was already en route for thé Crimea, turned about and employed against the penetration. Manstein's plan to break into the Crimea by surprise and take Sevastopol by a coup had failed. Instead, the Eleventh Army was now in danger of being cut off from the Crimea in the Nogay Steppe, and of being encircled and possibly destroyed in the narrow strip of land between the Dnieper line and the Black Sea.

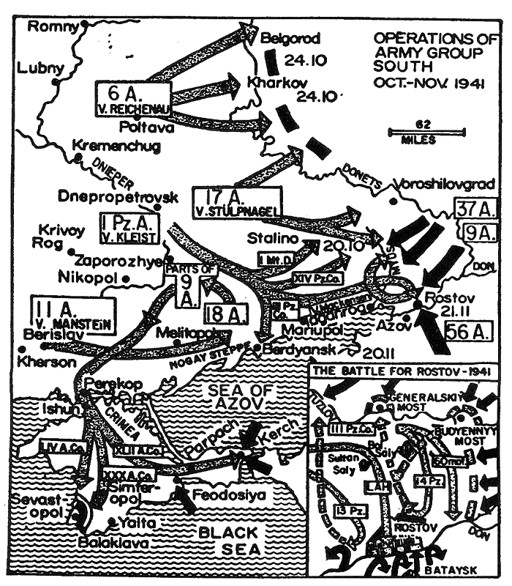

Map 13.

The Donets Basin, the Crimea, and Rostov were the strategic objectives assigned by Hitler to Army Group South for 1941.But in large-scale operations with their changing fortunes crises frequently turn into lucky chances. The two Soviet Armies which were putting such pressure on Manstein's divisions had neglected their flank and rear cover. That was to prove their doom—and that doom was Kleist. The 1st Panzer Group under Colonel-General von Kleist had discharged its task in the gigantic battles of encirclement at Kiev by the end of September and was then available for new operations. At Dnepropetrovsk General von Mackensen's III Panzer Corps had established and held a bridgehead over

the Dnieper and Samro. From this bridgehead and from Zaporozhye Kleist broke through the Soviet defences on the Dnieper, turned to the south in the direction of the Sea of Azov, and struck at the rear of the two Soviet Armies.

Before the Soviet High Command even realized what was happening its Armies, which had only just been on the point of annihilating Manstein's divisions, were themselves in the trap. Hunters became hunted, and offensive presently turned into flight. The battle of encirclement on the Sea of Azov raged across the Nogay Steppe, in the Chernigovka area, from 5th to 10th October.

The outcome was disastrous for the Soviets. The bulk of their Eighteenth Army was smashed between Mariupol and Berdyansk. The Army's Commander-in-Chief, Lieutenant-General Smirnov, was killed in action on 6th October 1941 and was found dead on the battlefield. More than 65,000 prisoners trudged off to the west. Two hundred and twelve tanks and 672 guns fell into German hands. It was a victory. But far too often during these past three weeks had the fate of Eleventh Army been balanced on a knife's edge. No doubt the German High Command took this bitter experience at the southern end of the Eastern Front as a warning that reliable victories could not be won with dissipated forces and inadequately co-ordinated operations.

At long last, therefore, Manstein received the sensible instruction to storm only the Crimea with his Eleventh Army. The capture of Rostov was assigned to Kleist's Panzer Group, to which Eleventh Army was ordered to hand over first the XLIX Mountain Corps and presently also the SS Brigade "Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler."

But the decision came three weeks too late. If this order, which at last made allowance for the actual strength of Eleventh Army, had been issued three weeks earlier the Crimea would have fallen, and Sevastopol would very probably have been taken with a surprise coup by fast formations, as envisaged in Manstein's bold plan.

Three weeks are a long time in war. And turning time to good profit was one of the outstanding skills of the Soviet High Command. As it was, Manstein and his Army were now faced with a protracted and costly battle.

- The Battle of the Crimea

Ghost fleet between Odessa and Sevastopol-Eight-day battle for the isthmus—The Askaniya Nova collective fruit farm- Pursuit across the Crimea—"Eight girls without baskets"— First assault on Sevastopol—In the communication trenches of Fort Stalin—Russian landing at Feodosiya-Disobedience of a general—Manstein suspends the attack on Sevastopol-The Sponeck affair.

ON 16th October, while the Soviet High Command was evacuating Odessa, until then surrounded by the Rumanian Fourth Army, and transferring the evacuated units to the Crimea, General Hansen's LIV Army Corps was getting ready for the breakthrough into the peninsula north of the narrow neck of land at Ishun.

Corporal Heinrich Weseloh and Private Jan Meyer of the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, 22nd Infantry Division, doubled forward, arrived at the jumping-off line for the attack. The evening of 17th October 1941 was settling over the Sivash, the saline swamp separating the Crimea from the mainland. The crater-pitted ground at Perekop and the houses of Ishun looked eerie in the falling dusk. It was cold, and there was rain in the air.

To the right of the two infantrymen a forward artillery observer was on his knees, digging himself a foxhole for the night. To the left of them were the men of their own group, also digging. Weseloh and Meyer likewise dropped down on the cold ground and began to dig a hole to give them cover for the night.

Their trenching-tools rang softly as they struck the ground. The hollow was getting deeper. They pressed themselves into it, "They say down on the coast it's still quite warm at this time of year," said Weseloh. Jan Meyer nodded. He thought of his farm back home in Hanover and cursed: "This damned war!"

"Can't go on much longer," Weseloh comforted him. "A fortnight ago, up in the steppe, we took nearly 100,000 prisoners. Three weeks ago, at Kiev, 665,000 were taken, and a little while earlier, at Uman, another 100,000. They say that some 650,000 Soviets have been taken prisoner on the Central Front to date. And at Vyazma and Bryansk they seem to have had a very good bag only a few days ago —the communiqué said 663,000 prisoners. You add that up. It

makes over two million."

"I'd say there are just as many Russians about as ever," Jan Meyer grunted.

Just then a Soviet IL-15 fighter swept over their positions, firing several rounds from its cannon. Wreckage sailed through the air. The Soviets had complete air command down in the south. Even Major Gotthardt Handrick with his "Ace of Hearts" 77th Fighter Squadron was unable to do anything about it. The Soviets were vastly superior to him in numbers. In addition to ground-attack aircraft and fiighter bombers they had two formations of 200 IL-15 and IL-16 fighters permanently in action. For the first time the German troops were forced to make extensive use of their trenching-tools.

Dig in—that was the first and most important commandment in the battle for the Crimea. On the entirely bare ground of the Ishun salt steppe there was no other cover than a hole in the earth. And where the Red Air Force did not strike, the Soviet artillery did. It was established in superbly camouflaged emplacements, frequently protected by reinforced concrete and armour-plating; it was fully ranged on a number of well-chosen target points and would put down sudden concentrated heavy barrages. The German artillery found it difficult to get the Russian batteries.

In these circumstances the only protection was a well-dug foxhole. And not only for the infantry: every vehicle, every gun, every horse, had likewise to be hidden several feet deep below the surface.

Night lay over Ishun—the night of 17th/18th October. In their positions between the Black Sea and the salt swamps the infantry were waiting for the dawn. The Soviets also were waiting. They knew what was going to happen and were feverishly organizing the defence of the vital peninsula. Two days earlier, on 16th October, Stalin had evacuated Odessa, which had been encircled by the Rumanian Fourth Army since early August. Major-General Y. E. Petrov's coastal Army was to help defend the Crimea. By means of hurriedly improvised naval transports Petrov's coastal Army was to be switched to Sevastopol. It was a correct move. For if Man-stein succeeded in getting into the Crimea, Odessa would have lost its importance as a port and naval base on the Black Sea anyway. It was more important to hold the Crimea and, above all, Sevastopol. The quick withdrawal by sea of an entire Army from Odessa was a bold operation which few people would have expected the Soviet Union to pull off, inexperienced as it was in naval warfare.

Aboard thirty-seven large transports totalling 191,400 GRT and on a variety of large and small naval vessels the bulk of the coastal Army, some 70,000 to 80,000 troops, were embarked in a single night and, unspotted by the German Luftwaffe, shipped to Sevastopol. Admittedly, only the men were evacuated from Odessa. Horses and motor vehicles had to be left behind. The heavy guns were dumped in the harbour because there were no loading-cranes. The Soviet 57th Artillery Regiment went on board without a single gun, without a single vehicle, and without a single piece of equipment.

Petrov's forces were then sent into action on the Ishun front in forced marches, just as they had arrived at Sevastopol

—ragged and quite inadequately equipped.

For his thrusts across the isthmus Manstein had lined up three divisions of LIV Army Corps. Indeed, there was no room for more formations in the four-mile-wide corridor. Reading from left to right, they were the 22nd, 73rd, and 46th Infantry Divisions and parts of 170th Infantry Division. Behind them stood XXX Corps with the 72nd, the bulk of the 170th, and the 50th Infantry Divisions. Still on the road, but later to follow the attacking Corps of Eleventh Army, was the XLII Corps with 132nd and 24th Infantry Divisions. The Fuehrer's Headquarters had made this Corps available to Manstein on condition that its divisions were moved across into the Kuban area from Kerch as quickly as possible, to advance to the Caucasus.

Manstein's six divisions were opposed by eight field divisions of the Soviet Fifty-first Army; to these must be added four cavalry divisions, as well as the fortress troops and naval brigades in Sevastopol. Moving towards the front were

General

Petrov's units from Odessa.It seemed as if the night would never end. The forward observers were lying behind their trench telescopes. The riflemen were crouched in their two-men foxholes, pressed close together, shivering. Immediately behind the most forward infantry positions were the guns of the medium artillery and the smoke mortars which were to be used here

for the first time in the sector of Eleventh Army. They were hidden by earth ramparts and camouflage netting. In position farther back was the heavy artillery with its 15- and 21-cm. guns. At 0500 hours a gigantic thunder-clap rent the grey dawn. The battle for the Crimea was opening with a tremendous artillery bombardment from every gun in Eleventh Army. It was an inferno of crashing noise, flashes of fire, fountains of mud, smoke, and stench. With a roar and a scream the smoke mortar rockets with their fiery tails streaked towards the enemy positions, showering the defenders of the isthmus of Ishun with a hail of iron and fire.

The time was 0530. The inferno was only 100 yards in front of the positions of the assault regiment. For a moment the barrage was silent. Then it started again, but this time the shellbursts were farther away: the guns had lengthened their range. That was the signal for the infantry. The men scrambled out of their earth-holes. "Forward!" They charged.

Machine-guns gave them covering fire. Mortars were keeping enemy strongpoints quiet.

But the German artillery bombardment had not put the Soviets out of action in their long and carefully prepared positions. Russian machine-guns opened up. Soviet artillery fired well-aimed salvos and time and again forced the attackers to take cover.

Only step by step could the charging infantrymen gain ground. On the left wing Colonel Haccius of the 22nd Infantry Division from Lower Saxony made a penetration in the enemy lines with his battalions of 65th Infantry Regiment and seized the fortified ridge of high ground which blocked the passage. But heavy enemy gunfire forced them to dig in.

Things went less well in the sector of 47th Infantry Regiment. The assault companies got stuck in front of a powerful wire obstacle and were shot up by the Soviets. Those who were not killed worked their way back. The 16th Infantry Regiment, 22nd Infantry Division, had to be brought up from reserve positions; it made a flanking attack and rolled up the Soviet defences in front of 47th Infantry Division. The advance was resumed. The so-called Heroes Tumulus of Assis, a commanding earth mound in an otherwise completely flat terrain, was stormed by men of 47th Infantry Regiment. But the Russians did not surrender. They died in their foxholes and trenches.

In the sector of 73rd Infantry Division, on the right of 22nd Infantry Division, the regiments also gradually gained ground. And on the right wing units of 46th and 170th Infantry Divisions worked their way into the strongly fortified system of Soviet defences.

But these deeply staggered defences seemed to have no end to them—wire obstacles and more wire obstacles, thick minefields with wooden box mines which did not respond to the sappers' detectors, as well as emplaced and remote- controlled flame-throwers. Moreover, buried tanks and even electrically detonated sea-mines completed these "devil's plantations" which the gallant sappers had to weed.

Field position after field position had to be taken by the infantry in costly fighting through these mile-deep defences. Frequently the situation was saved only by the assault artillery employed in support of the infantry: the lumbering monsters of the Self-propelled Gun Battalion 190 breached the wire obstacles and pillbox lines for the infantry companies. The battle raged for eight days—eight times twenty-four hours. At last the entrance to the Crimea was forced at several points. Even Petrov's coastal Army had been unable to prevent this. According to Colonel P. A. Zhilin, that Army lost most of its men and equipment during the last three days of the fighting for the isthmus. Zhilin ascribed these heavy casualties to "massed German tank attacks." He is mistaken. Manstein had no tank formations at all. They were Major Vogt's two dozen self-propelled guns of Battalion 190—known as the Lions after their tactical sign—which, together with 170th Infantry Division, decisively smashed General Petrov's coastal Army.

At the same time Eleventh Army command could not help noticing that the battle strength of its own assault formations had begun to decline during these days of heavy fighting. The 25th and 26th October, in particular, had seen many crises. And on 27th October there had been some fierce engagements with Petrov's Odessa regiments before the Soviet resistance weakened.

Manstein therefore fixed 28th October as the date for the final breakthrough strike. But this blow did not connect: the Soviet Fifty-first Army had abandoned its positions under cover of darkness and withdrawn to the east. The remnants of Petrov's coastal Army were streaming south in disorder, in the direction of Sevastopol. The German breakthrough into the Crimea had come off.

Eleventh Army could now go over to the pursuit. In the office building of the Askaniya Nova collective fruit farm, just under 20 miles north-east of Perekop, runners came and went ceaselessly on 28th October. In the large conference room of Army headquarters Manstein's chief of operations, Colonel Busse, had spread out his situation maps. Arrows, lines, little circles, and flags marked the incipient flight of the Russians.

Towards noon Manstein entered the map-room together with Colonel Wöhler, the Chief of Staff of Eleventh Army. "What d'you think of the situation, Busse?" Manstein asked his chief of operations. "Are the Russians going to give up the Crimea?"

"I don't think so, Herr General," Busse replied.

"Neither do I," Manstein returned. "If they did they would lose control of the Black Sea and throw away their strong positions threatening the flanks of our Army Group South. They won't do that in a hurry. Besides, it would be rather difficult to embark two Armies and get them away."

Wöhler pointed at the map. "The Russians are certain to try to hold Sevastopol, Feodosiya, and Kerch. They will save their defeated troops by getting them into these redoubts; there they will replenish them and send them into attack again. So long as they hold the naval fortress of Sevastopol they are able to do that."

"That's just what we've got to prevent," Manstein retorted.

Busse nodded. "But how are we going to turn our infantry into mobile formations? If only we had a Panzer or motorized division! It would make things a lot easier."

Colonel Wöhler took this as his clue. "We'll amalgamate all available motorized sections of infantry divisions, from reconnaissance detachments to anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns, and send them forward as a fast combat group!" Busse wholeheartedly agreed with the idea.

"Very well," Manstein decided. "Busse, you'll see that such a combat group is formed. Colonel Ziegler is to lead it. His first objective is to be Simferopol, the main city and transport centre of the peninsula. The way to Sevastopol and the south coast lies through that town. And that way has got to be blocked."

Manstein picked up a coloured crayon. With a few quick strokes he sketched out his operational plan on the map: the XXX Army Corps with 22nd and 72nd Infantry Divisions would advance behind Ziegler's fast combat group via Simferopol and Bakhchisaray to the south coast—to Sevastopol and Yalta. The newly arrived XLII Army Corps with 46th, 73rd, and 170th Infantry Divisions would move towards Feodosiya and the Isthmus of Parpach. The LIV Corps was to drive south with 50th and 132nd Infantry Divisions, straight towards Sevastopol. Perhaps the fortress could be taken by a surprise attack after all.

Other books

Blood-Kissed Sky (Darkness Before Dawn) by London, J. A.

Two for Tamara by Elle Boon

The Double Cross by Clare O'Donohue

A Little Revenge Omnibus by Penny Jordan

Maps for Lost Lovers by Nadeem Aslam

Slow Burn by V. J. Chambers

His Expectant Lover by Elizabeth Lennox

The Opposite of Loneliness: Essays and Stories by Marina Keegan

Until I'm Yours by Kennedy Ryan

Wrong About Japan by Peter Carey