Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (56 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

The Soviet High Command set about its plan correctly. Kluge's Fourth Army, in the middle of Army Group Centre, was at first exposed only to tying-down attacks. In this way the Soviets tried to prevent Kluge from switching some of his forces to the wings of Army Group, or even withdrawing his Army and employing the large formations thus freed against the Soviet offensive in the south and north. Kluge was to be pinned down in the middle of the central sector until the two jaws formed by the northern and southern Russian Army Groups had smashed the wings of the German front.

It was in just this way that Field-Marshal von Bock had dealt with the Soviets at Bialystok and Minsk, Hoth at Smolensk, Rundstedt at Kiev, Guderian at Bryansk—and Kluge at Vyazma, which was the finest example of a battle of encirclement in military history. Was Zhukov now going to do the same, this time with a Russian victory at Vyazma?

It could happen, provided the Soviets succeeded in breaking through to the west, also north of Fourth Army, and in wheeling round to the south, towards the Moscow-Smolensk motor highway.

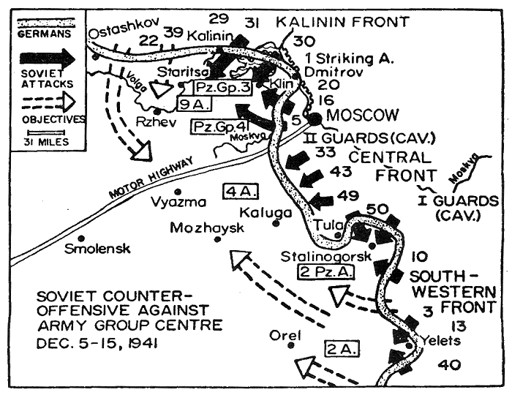

Map 16.

Turning-point before Moscow. In a grand offensive the Soviet High Command hoped to surround and annihilate the exhausted Armies of Army Group Centre in the approaches to Moscow.What meanwhile was the situation on the front of 4th Panzer Group? The VII and IX Army Corps had ground to a standstill along the Moskva-Volga Canal at the beginning of Novembei. The IX Army Corps made one last attempt to improve its positions. One of the participants in this attempt —in these last pulse beats of the German frontal attack on Moscow by Hoepner's 4th Panzer Group along the motor highway—was Lieutenant Hans Bramer with his 14th Company, 487th Infantry Regiment, fighting under 267th Infantry Division. That was on 2nd December 1941.

The 267th Infantry Division from Hanover was to make one last attempt to break open the Soviet barrier west of Kubinka by means of an enveloping attack across the frozen Moskva river. In a temperature 34 degrees below zero Centigrade it took hours to start all the vehicles needed to get the men and the heavy weapons into the deployment area. The artillery, on the other hand, put down a massive barrage as in the good old days. But, in spite of it, the move did not come off. The Russians had fresh Siberian regiments in magnificently camouflaged and well-built positions in the woods. As a result, the normally so useful 3-7-cm. anti-tank guns of Brämer's 14th Panzerjäger Company were not much help, even though two troops with six guns had been attached to the assault battalions of Liuetenant-Colonel Maier's combat group. The gun crews were killed. The guns were lost. That was the end. The men had to withdraw again. They simply could not get anywhere.

The 267th Infantry Division thereupon took up its prepared winter positions a few miles farther to the north, on the western bank of the Moskva, now in the role of left-wing division of VII Corps. Beyond it to the north stood IX Corps with 78th, 87th, and 252nd Infantry Divisions. In this way the line as far as Istra was reasonably well held.

But over on the right, along the Moskva river, 267th Infantry Division, supposed to hold a sector of roughly four miles with the remnants of the weakened 497th Infantry Regiment, could do no more than man a few strongpoints, scarcely more than reinforced field pickets. It was asking for trouble.

During the next few days the Russians continually attacked across the Moskva—sometimes with small formations and sometimes in strength. Evidently they were trying to discover the weak spots along the join between Hoepner's 4th Panzer Group and Kluge's Fourth Army. Supposing they discovered the virtually undefended gap along the Moskva on the right flank of 267th Infantry Division? The defenders kept pointing out their weakness—but without effect, since neither Corps nor Army had any reserves left which they could have dispatched to reinforce the line.

On llth December towards 1000 hours a runner, Corporal Dohrendorf, excitedly burst into Brämer's dugout: "Herr Oberleutnant, over there on the right there are columns on skis moving to the west. I believe they are Russians!"

"Blast!" Bramer leapt to his feet and ran out. His field-glasses went up. A suppressed curse. Bramer scurried back to the telephone. Report to Regiment: "Soviet forces, several big columns in battalion strength, are passing through the front line to the west on skis." Action stations.

Corporal Dohrendorf and Lieutenant Bramer had observed correctly. Soviet Cossack battalions and ski combat groups had wiped out the German pickets along the thinly held Moskva strip and were now simply bypassing the well- fortified strongpoints of 467th and 487th Infantry Regiments, where the bulk of divisional artillery was also emplaced.

In vain did General Martinek, commanding 267th Infantry Division, try to stop the gap with the battered companies of his 497th Infantry Regiment. He did not succeed. The Russians enlarged their penetration. Contact was lost between divisional headquarters and the two northern regiments.

The division next in the line, the 78th, which was now being threatened in its flank and rear by the Soviet penetration, flung in units of its 215th Infantry Regiment. Colonel Merker, commanding 215th Infantry Regiment, assumed command in the penetration area, and from units of 467th and 487th Infantry Regiments, 267th Artillery Regiment, and with the support of battalions and batteries of Army artillery, built up a new defensive front.

But the Russians operated very skilfully, cunningly, and boldly in the wooded country. That was hardly surprising: the units were part of the Soviet 20th Cavalry Division—a crack formation of Major-General Dovator's famous Cossack Corps, given Guards status by Stalin on 2nd December 1941 and now proudly bearing the name of II Guards Cavalry Corps.

After their break-through the Cossack regiments rallied at various key points, formed themselves into combat groups, and made surprise attacks on headquarters and supply depots in the hinterland. They blocked roads, destroyed communications, blew up bridges and viaducts, and time and again raided supply columns and wiped them out.

Thus on 13th December squadrons of 22nd Cossack Regiment overran an artillery group of 78th Infantry Division 12 miles behind the front line. They threatened Lokotnya, a supply base and road junction. Other squadrons thrust north behind 78th and 87th Divisions.

The entire front of IX Corps now hung in the air. The forward positions of the divisions were intact, but their rearward communications had been cut off. Supplies of ammunition and food did not get through. And there were several thousand wounded in the forward fighting area.

On 14th December, at 1635, a Cossack squadron attacked the 10th Battery, 78th Infantry Division, 16 miles behind the front, while the German battery was on the move to new positions farther back. The Cossacks attacked with drawn sabres. They cut up the surprised artillerymen and slaughtered men and horses.

The Russians likewise tried to break through along the Moscow highway and the old postal road, where 197th Infantry Division was guarding the supply routes. But the 197th was on the alert. Wherever the Russians made penetrations with tanks they were pinned down by concentrated fire and dislodged by immediate counter-attacks. Thus it went on day after day. At 0300 the Soviets would come out of the villages, where they h:.d been keeping themselves warm,

and in the evenings they would go back. They would take their wounded with them, but leave their dead behind.

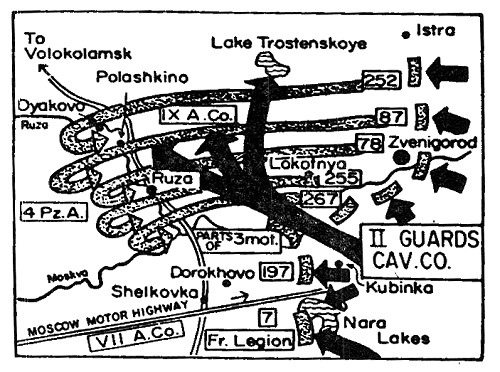

Map 17.

Dovator's Cossack Corps strikes at the rear of IX Army Corps.During the night of 13th/14th December a supply column of the Cossacks, consisting of forty lorries, tried to get past the positions of 229th Artillery Regiment, 197th Infantry Division.

The temperature was 36 degrees below zero Centigrade. The recoil devices of many of the guns were frozen up. The lenses of the gunsights were frosted over and blind. The gunners scored hits nevertheless just by firing by eye. The Cossack column was smashed up at point-blank range.

But neither the determined resistance of the line along the motor highway nor the gallantry of the grenadier and artillery battalions of 197th Infantry Division, nor yet the tough and successful defensive fighting of 7th Infantry Division, in whose ranks the French volunteers also fought, was able to avert the general disaster triggered off for VII and IX Army Corps by the Cossack Corps' penetration north of the highway. There was only one thing to do—pull back the front along the entire right wing of 4th Panzer Group. The new main line for the defensive fighting was to be the Ruza line, 25 miles behind the present front line. In exceedingly hard righting the 197th Infantry Division, together with rapidly brought-up units of 3rd Motorized Infantry Division, held open the highway at the now famous, or infamous, Shelkovka-Dorokhovo crossroads for the withdrawal of the heavy equipment and the divisions of 4th Panzer Group.

The situation is well illustrated by the Order issued by 78th Division to its regiments for the withdrawal: "The main thing is to break through the enemy's barrier behind our front line. If necessary, vehicles are to be left behind and only the troops saved."

In this manner they fought their way back: the Swabians of 78th Infantry Division, whose tactical sign was Ulm Cathedral and the iron hand of Götz von Berlichingen, the Thuringians of 87th Division, the Silesians of 252nd Division, the men from Rhineland and Hesse of 197th Infantry Division, and the battalions of 255th Infantry Division. The French legionaries trudged along next to the Bavarians of 7th Infantry Division, and their words of command in the language of Napoleon echoed eerily through the frosty nights and the icy blizzards— just as 129 years before.

Lieutenant Bramer of 267th Infantry Division and his men were now, in December, retreating along the road by which they had advanced earlier in the autumn. They were carrying their wounded with them: two infantrymen were leading

a captured Cossack horse on which sat a corporal whose leg had been torn off by à shell-splinter as far as the knee. The wound was frozen up, and in this way bleeding had been stopped. Only willpower kept the man in the saddle. He wanted to live. And in order to live one had to make one's way westward.

Who was the man who won these victories between Zveni-gorod and Istra? Who was the man in command of the Cossacks who had broken through along the flank of VII Corps, dislodging IX Corps and forcing its divisions to retreat? His name was Major-General Dovator. This Cossack general must have been a superb cavalry commander. Within the framework of the Soviet Fifth Army he led his Corps with extraordinary skill, daring, and dash. He led his fast cavalry formations in the manner of a tank commander—and, after all, armour was merely the mechanized successor of the old cavalry.

"A commander must be in front," was Dovator's motto. And he led his troops from the front. He and his headquarters squadron were invariably in the front line. More than once Major-General Dovator was cited in the Soviet High Command communiqué for personal bravery.

Soviet military sources say nothing about his origins, which rather suggests that they were not proletarian but bourgeois. He probably came from the Officers' Corps of the old Tsarist Army—one of those men of middle-class origin who embraced the military profession and became unreserved supporters of the Bolshevik regime.

252nd Infantry Division, the "Oak Leaf" Division from Silesia, was among the divisions which had to fight their way back to the Ruza line. It was this division which took its revenge on Dovator's Cossacks and made the general pay the supreme price for his victory—his life.

Other books

Garrett's Choice by A.J. Jarrett

Savage Hero by Cassie Edwards

That Summer (Part One) by Lauren Crossley

Cactus Flower by Duncan, Alice

The Terrorist Next Door by Sheldon Siegel

Untamed by Nora Roberts

Diary of a Male Maid by Foor, Jennifer

The Riddle of St Leonard's by Candace Robb

Three For The Chair by Stout, Rex

When the Nines Roll Over by David Benioff