Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (62 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

When their wireless-sets packed up because of the hard frost, communications officers were appointed in each Soviet unit who would see to it that orders and reports were carried from unit to unit by the quickest possible route—on horseback, by horse-drawn sleigh, or on skis. Moreover, an aerial communications group was organized, equipped with old-fashioned but sturdy light aircraft. In the difficult wooded country these proved an important aid to orientation.

Finally, there was propaganda. The Soviets spent more time and effort on propaganda than on food supplies for their

troops. Up to the very last minute before an attack political officers belaboured the hearts and minds of the Red Army men with stirring slogans. The rousing slogans took the place of the issue of brandy of former days. The combined effect of slogans and spirits was often terrible.

Yeremenko writes:

In order to stiffen our formations, hundreds of Communist Party and Komsomol members were attached to them from rearward formations. Workers from the Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk areas visited the troops in their starting-lines at the front. Sitting in their trenches and positions, the men from Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk chatted with the troops, telling them about their successes on the industrial front. They gave a pledge to the soldiers to produce even more and to supply the fighting front with whatever it needed for victory over the enemy. The soldiers and officers, in turn, solemnly promised to fight bravely and fearlessly, to crush the enemy and honourably to discharge their duty.

Party and Komsomol meetings were held in all formations and units at the front. Communist Party and Komsomol members undertook solemn obligations to set an example to the rest in the impending battle, not to spare themselves, but to be an inspiration to every one. In this way the representatives of the Party among the troops in the field created the prerequisites for a vigorous and successful discharge of the military tasks on each sector.

The scale on which the political fanaticism of the Communist Party was mobilized in the military machine is revealed very clearly in Yeremenko's account. The Marshal records: "249th Rifle Division included in its ranks 567 members and 463 probationary members of the Communist Party, as well as 1096 Komsomol members." That was a quarter of the Division's combat strength.

"Assignments which require the greatest sense of responsibility," Yeremenko further reports, "were given to Komsomol members. Thus in the 1195th Rifle Regiment, 360th Rifle Division, all the No. 1 machine-gunners, all sub- machine gunners, and all the scouts were Komsomol members."

Yeremenko's offensive erupted on 9th January 1942. "Attack," the Marshal writes, "is an ordinary, everyday word to the soldier. At that time, however, in the winter of 1941— 42, it had a solemn ring. That word contained our hope of smashing the enemy, of liberating our native land, of saving our near and dear ones and all our fellow countrymen who had fallen under fascist servitude; it contained our hopes of revenge against a perfidious enemy and our dream of peaceful life and peaceful work."

A little bombastically Yeremenko concludes: "And every soldier, from the supply-column driver to the assault-unit man, was dreaming of attack as the most wonderful and important thing in his life."

This is what the "most wonderful and important thing," which, according to Yeremenko, every Red Army man was dreaming of, looked like in reality. Two hours of artillery bombardment; infantry attack with two divisions through breast-deep snow towards the town of Peno; charge over the ice straight into the machine-gun fire of the German front.

Peno was taken on the second day of the offensive after heavy and costly fighting. The reconnaissance detachment of Fegelein's SS Cavalry Brigade was overrun. The first breach had been punched for Yeremenko's break-through.

But the two wings of the Soviet Army did not succeed in making any real progress in spite of their colossal superiority. The Russian 360th Rifle Division came to a halt in front of the positions of the 416th Infantry Regiment from Brandenburg. On the left wing, on Lake Volgo near Bor and Selishche, the Russian 334th Rifle Division was badly mauled by the Westphalian 253rd Infantry Division and thrown back again.

But at the centre of the attack the Russian 249th Rifle Division made further progress. It was a crack unit, shortly afterwards to be raised by Stalin to the rank of 16th Guards Division and decorated with the Order of Lenin. Major- General Tarasov swept on with his division towards Andrea-pol. His objective was a break-through towards Toropets, the traffic junction and German supply base, Yeremenko's coveted "bread-basket." His road to the food-dumps was

blocked by the Silesian 189th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Hohmeyer, which had been rushed post-haste to Andreapol. The regiment belonged to 81st Infantry Division and was reinforced by 2nd Battalion, 181st Artillery Regiment, as well as a sapper company and a few supply units.

Yeremenko repeatedly pays tribute to the feats and self-sacrifice of this German regiment. It caused a lot of difficulties for his Army, at the centre of its attack, and resisted two Soviet crack divisions literally to the last man, inflicting serious casualties upon the foremost divisions of the Fourth Striking Army.

The tragedy of the Silesians and Sudeten Germans of 189th Infantry Regiment was enacted between the railway station of Okhvat and the villages of Lugi, Velichkovo, and Lauga. Only a few men survived the ferocious battle against Yeremenko's Guards in three feet of snow and a temperature of 46 degrees below. One of the few survivors of the 189th, in a position to describe the extinction of his regiment, is First Lieutenant Erich Schlösser, who participated in the fighting before Andreapol as an NCO in the 3rd Company.

The 81st Infantry Division, to which the 189th Infantry Regiment belonged, had gone through the campaign in France without appreciable losses. Just before Christmas 1941 the division was in quarters along the Atlantic coast, enjoying a distinctly cushy billet.

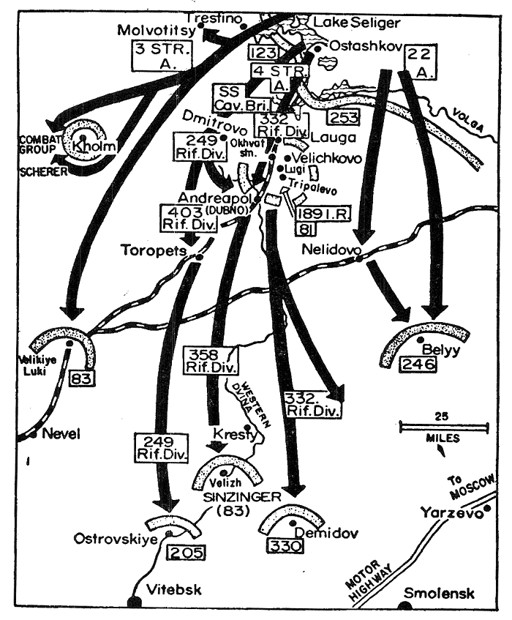

Map 19.

At the beginning of January 1942 the German front was ripped open also along the junction between Army Group Centre and Army Group North. The Soviet Fourth Striking Army is aiming at Vitebsk and Smolensk.But they were not to enjoy any Christmas festivities there on the Atlantic coast. On 22nd December 1941 came the order: Prepare for departure. On 23rd December the companies clambered aboard their train. Where were they off to?

It did not look like a long journey. They had not been issued with any special food or with winter clothing. They had received no new weapons and no equipment of any kind.

No one believed the rumour which was slowly making its way through the train from the regimental staff: We are off to the Eastern Front—to Russia!

Monotonously the wheels clanked over the rails all the way across France. The men spent Christmas Eve in the straw of their goods wagons. They were beginning to shiver in their light-weight coats. On they went, through Germany.

Then through Poland. In Warsaw they were issued with food. When they drew their next issue they were well inside Belo-russia—at Minsk. The temperature was 25 degrees below, and the cold was seeping through the sides of the wagons. The primitive stoves were red-hot. But the men were miserably cold.

After thirteen days of uninterrupted journey the companies clambered out of their train on 5th January 1942. They stood at the station of Andreapol, in three-foot-deep snow and a temperature 30 degrees below. There was not a single winter greatcoat between them, There were no balaclava helmets and no ear-muffs. Before they knew what had happened to them many men had their toes and ears frozen off.

The war diary of II Corps records: "The regiment's total lack of winter requirements defies description." But before it was possible to supply the regiment, which had a mobilization strength of barely 3000 men, with even the most urgent necessities it was ordered into action against Yeremenko's Guards Regiments of 249th Rifle Division, who were pouring through the breach at Peno and south-west towards Andrea-pol. Soviet ski battalions were already racing across Lake Okhvat.

Colonel Hohmeyer flung his battalions into their path. The 3rd Engineers Company 181 was put under his command.

The 1st Battalion, 189th Infantry Regiment, reinforced by a battery of 181st Artillery Regiment, arrived in the village and at the station of Okhvat at exactly the same time as the Russian vanguards. The Russians seized the eastern edge of the small town, while Captain Lindenthal's 3rd Company hung on grimly to its western edge. The Soviet 249th Rifle Division sent its 925th Regiment into action—Siberians who charged across the frozen lake with shouts of Urra.

Hohmeyer also switched his 3rd Battalion to Okhvat.

By the railway embankment Captain Neumann was trying to ward off the Russian attacks with his llth Company and to relieve the 1st Battalion at Okhvat. The Russians had to be halted—at least long enough for a stop-gap line of defence to be established in the wide breach between Dvina and Volga. Unless that was done the Soviet divisions would drive on to their objectives—Vitebsk, Smolensk, and the motor highway —in order to link up with the Soviet Armies attacking from the south and to close the trap around Army Group Centre.

Sergeant Maziol with his platoon was in position at the south-western edge of Okhvat. "Tanks!" Corporal Gustav Praxa suddenly shouted into the peasant hut. Everybody out! From the entrance to the village came the first tank, a light T-60. In line behind followed another, then a second and a third—eight in all. They were a combat group of the Soviet 141st Tank Battalion.

The tanks fired into the houses. They tore the thatched roofs to shreds. Clearly they intended to wreck anything that could serve the Germans for accommodation. It was a typical Russian fighting method.

Maziol, together with Praxa and Sergeant Müller, who led the 1st section, were lying behind the corner of a house. An enemy tank on the far side of the wide village street was spraying the ground with machine-gun fire, churning up the snow and pinning down the three men.

"If they get past us they'll shoot up our supply vehicles and keep on to Andreapol," Maziol observed in his unmistakable Silesian accent. Then he added in a matter-of-fact way: "We've got to finish them off with grenades."

Müller and Praxa understood. With numb fingers they got their hand-grenades ready. Already the first of the T-60s came rumbling past the corner.

That was Müller's moment. He leapt to his feet, ran alongside the tank, and swung himself up on its stern. He grabbed the hatch-handle. He tore open the hatch. He held it open with his left hand while his right clutched his egg grenade. With his teeth he pulled the detonator ring, calmly waited two seconds, and then dropped the egg into the tank. He flung himself down. A crash. A sheet of flame.

The second tank stopped. Its hatch opened. The Russian wanted to have a quick look to see what was happening. It was just long enough for Maziol to get him into the sights of his machine pistol. A burst spat from his barrel. The Russian dropped backward into the turret. And already Müller was on top of the tank, dropping a stick grenade into the still open turret-hatch.

The two tanks were enveloped in black smoke which blanketed out the road. Like a phantom the third tank emerged through the smoke. Abruptly it tried to reverse, but got stuck in the snow.

Corporal Praxa leapt on to its turret, but could not open the hatch. But the Russian gunner was just opening it from inside. He wanted to have a quick look round. On catching sight of Praxa he immediately ducked again. But the hand- grenade rolled in just before the hatch closed.

Seeing the disaster that had befallen the spearhead of their combat group, the remaining five Soviet tanks careered around wildly in the deep snow. Eventually they about-turned in the wide village street and retreated.

At dusk the Siberians of 925th Rifle Regiment came again. To support them General Tarasov this time employed the 1117th and 1119th Rifle Regiments, 332nd Rifle Division. Lieutenant-Colonel Proske's 1st Battalion was badly mauled. Captain Neumann's llth Company, fighting by the railway embankment, also had to give ground.

During the night of 12th/13th January the thermometer dropped to 42 degrees below. In each company some twenty to thirty men were out of action because of severe frostbite.

Other books

Defensive by J.D. Rivera

Coletti Warlords: Reality Bites by Gail Koger

Smile and be a Villain by Jeanne M. Dams

Rocky Mountain Wild (Rocky Mountain Bride Series Book 6) by Lee Savino

Mysterious Cairo by Edited By Ed Stark, Dell Harris

Death of a Hussy by Beaton, M.C.

Honored Guest (Vintage Contemporaries) by Williams, Joy

Beyond the Shadows by Jess Granger

A Hint of Rapture by Miriam Minger

A Beautiful Lie by Irfan Master