Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (23 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

Some of this newfound obscenity probably reflects a change in the way speech was recorded in the various court rolls. In the Middle Ages, the records were often entirely in Latin and French, with the actual English words at issue included only occasionally. By the sixteenth century, the records were in English or in a mixture of English

and Latin, so there was much more scope for insults to be written down at length. But these court records also reflect a move from oaths to obscenities as the language of emotive power. People didn’t need to accuse each other of “fucking” in the Middle Ages, because the word

fuck

wasn’t any worse than

lie with, have to do with

, or

adulteravit

. By the sixteenth century,

fucking

was becoming a more powerful word, so people began to employ it more and more frequently when they wanted to wound.

A genre of poetry called flyting exemplifies this new use of obscene words to injure and insult. Flyting was very much like the freestyle battles of today, in which rappers compete to insult each other in the most creative ways. While freestyle battling is a “street” art form, practiced mostly by disenfranchised youth, flyting was entertainment for the nobility. The most famous practitioner, William Dunbar, of the early

fukkit

, was a Franciscan friar, and even Scottish kings tried their hand. A typical example is this exchange between Friar Dunbar and Walter Kennedy, a court poet.

Kennedy to Dunbar:

Skaldit skaitbird

and commoun skamelar,

Wanfukkit funling that Natour maid ane yrle …

[Diseased vulture and common parasite,

Weakly conceived foundling that Nature made a dwarf …]

Dunbar to Kennedy:

Forworthin wirling, I warne thee, it is wittin

How, skyttand skarth, thow hes the hurle behind.

Wan wraiglane wasp, ma wormis hes thow beschittin

Nor thair is gers on grund or leif on lind.

[Deformed wretch, I warn you, it is known,

How, you shitting hermaphrodite, you have diarrhea behind.

Sad wriggling wasp, you have beshit more worms

Than there is grass on ground or leaf on linden tree.]

The sixteenth century is a turning point in the history of swearing in English, as epitomized by Florio’s

cazzica

, “an interjection of admiration and affirming, what? gods me, god forbid, tush.” Where an Italian would employ an obscenity, an English person, Florio indicates, would still use a vain oath. But from this point on, the balance will tip heavily in favor of obscenity, until four hundred years later we get

motherfucker

, an interjection of admiration and affirming.

You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself

In the sixteenth century, obscene language was developing both as a moral phenomenon and as a social one. The moral aspect came from the Middle Ages and ultimately from the Bible, but the seductive force that used to be spread across an entire sinful sentence was becoming concentrated in a few lascivious little words for certain body parts and actions. The social aspect developed in the web of relationships at the new, nonfeudal court, where speech and writing were tools employed by courtiers as they jockeyed for the favor of the monarch on whom they were more and more dependent. This period saw a great “

advance in the frontiers of shame

,” as Norbert Elias puts it. Sixteenth-century people were ashamed of more things than their medieval forebears, and ashamed in front of more people. It became more and more important to conceal these various shameful body parts and actions, in public life and in polite language.

Innovations in sixteenth-century architecture allowed for what scholars talk about as the “invention” of privacy, necessary for this increased delicacy of shame. Of course, solitude wasn’t a Renaissance invention—people in the Middle Ages sometimes found themselves alone, though not as often as we do—but it was only after the proliferation of spaces in which people could reliably be alone that something like our notion of privacy developed, the feeling that there were certain things that belonged solely to an individual and that must not be shared with or shown before other people.

Even confession, the

most secret of all the sacraments, was not private, in our sense of the word, for much of the Middle Ages. You might have told your sins to the priest and God alone, but the priest very likely would have imposed on you a public penance—wearing sackcloth, missing Communion—to be performed in front of the entire community. The whole parish would thus have known about the “private” sins you confessed to the priest.

Reading too was very often not private

but a group activity: a poet reciting his poems to entertain the court, a lady reading from a book to entertain her friends, a monk reading from the Bible to his brethren in their monastery. Books were so rare, heavy, and expensive that no one ever curled up in an armchair to read to him- or herself. (Also, there were, as far as historians can tell, no comfortable chairs for most of the Middle Ages—you sat on either long benches or large, unpadded wooden chairs.) Even in the sixteenth century, people were suspicious of privacy—who knew what you could get up to all by your lonesome, with only the devil for company? In the Middle Ages, then, there was little that was private as we think of it, and even if people occasionally found themselves alone in the woods, this was not necessarily seen as a desirable thing.

In the Renaissance, people started building houses with more rooms. They needed more rooms, because suddenly they were accumulating more stuff. In a region of England called the Arden, to take just one small area, people amassed possessions at an astounding rate in the years between 1570 and 1674.

Historian Victor Skipp

calculates that possessions increased 289 percent among the wealthy, 310 percent among the “middling sort,” and even 247 percent among the poorer classes during these years.

*

To see what this

looked like in practice, Skipp compares the goods possessed by two farmers with approximately the same size landholding in 1560 and in 1587. Edward Kempsale, the first farmer, lived in a house with two rooms, and his household goods at his death consisted of six plates, three sheets, one coverlet, and two tablecloths. Thomas Gyll, in contrast, lived in a house with four rooms, and left more than twenty-eight pieces of pewter, five silver spoons, thirteen and a half pairs of sheets, six coverlets, and four tablecloths, as well as pillows, pillowcases, and table napkins. Master Gyll could build extra rooms to store and display his pewter and his thirteen and a half pairs of sheets thanks to a technological innovation—the fireplace.

Around 1330, fireplaces

were developed that would not collapse under the intense heat generated by a confined fire. The central open fire of the hall could be replaced with a fireplace and chimney; you could then add rooms above the hall, which previously had been impossible because the smoke needed to go out through a hole in the roof. These rooms could be given their own fireplaces, and could then be used even in the winter. Bill Bryson, shrewd observer of human nature, summarizes what happened next: “Rooms began to proliferate as wealthy householders discovered the satisfactions of having space to themselves… . The idea of personal space, which seems so natural to us now, was a revelation. People couldn’t get enough of it.” Houses began to have bedrooms, studies, dining rooms, and parlors—they began, slowly, to look more like houses as we know them today.

The notion of privacy evolved slowly, even with these extra rooms. People who used to sleep together in the straw of the great hall would now bed down in a bedroom, but they still likely would be sleeping with others. A (female) servant often slept on the floor of the room Samuel Pepys shared with his wife in the late seventeenth century; some of the servants found this arrangement perfectly normal, others, perhaps more attuned to the idea of privacy (or perhaps just more wary of Mr. Pepys), thought it odd.

Privies were also spaces

in which privacy could be achieved,

as their name suggests. There were two kinds of places one might leave a sirreverence—the privies or garderobes, which were small rooms that hung out over the walls of a castle or house and allowed waste to drop into a moat or river or onto the ground below, and closestools, which were chamber pots enclosed and somewhat disguised by a piece of furniture. These were usually placed in a bedroom or dining room but could still be at least notionally private, surrounded by a curtain. (

Sirreverence

comes from “save-reverence,” which people used to say before or after mentioning something likely to offend. The apology came to stand for the thing it excused, and so

sirreverence

came to mean “turd,” as in these lines from Shakespeare’s early rival Robert Greene: “

His head, and his necke

, were all besmeared with the soft sirreverence, so as he stunke worse than a Jakes Farmer,” a person who cleans out privies for a living.)

Garderobe

looks as if it should refer to a place to put clothes—it is Norman French for “wardrobe”—but came to be applied to privies because they were often built off wardrobes. Privies were also called, in ascending order of politeness,

jakes

or

sinkes, latrines, places of easement

, and

houses of office. Jakes

especially was vulgar and impolite; in his

Metamorphosis of Ajax

, Harington relates the story of a flustered lady-in-waiting who introduces Jaques Wingfield as “M. Privy Wingfield.” Privies were sometimes truly private one-seaters, where a person could read, think, sleep, or even, as King James I was rumored to have done, have sex. Often, however, they were still communal multiseaters, though much less grand than those of ancient Roman times, maxing out at around seven or eight seats. While it is possible to imagine eight people staring resolutely into space while they used the facilities, these were more likely social spaces. In the late seventeenth century,

the family at Chilthorne Domer

, a manor in Somerset, would congregate daily in their six-seater.

In 1596, though, Harington had mocked this custom as “French,” pretty much the worst insult an Englishman could throw at something in the Renaissance without resorting to sirreverence.

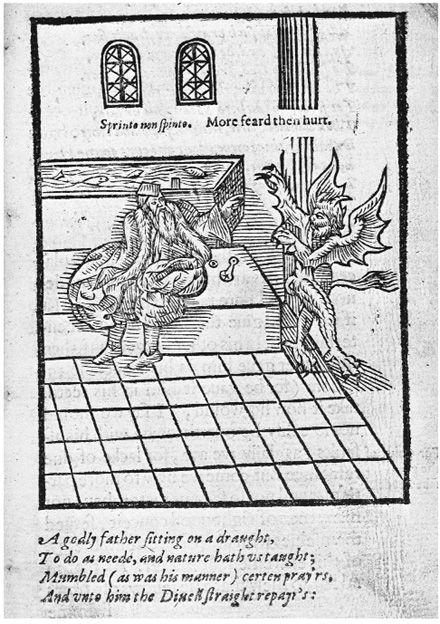

Harington suggests that multiseat privies are going out of fashion, that the most socially acceptable way to defecate is in privacy. A woodcut from his

Metamorphosis

illustrates this new custom of performing one’s bodily functions in private, while pointing out the potential dangers of such solitude—the devil comes to annoy the defecator. Harington was a member of high society, a courtier and Queen Elizabeth’s godson, and was ahead of the curve. He extolled the virtues of the private privy long before the country family, rusticated more than a hundred miles from London, thought to be ashamed of their bodily functions and started to discuss the day’s events at the breakfast table, not in the shithouse.

For true privacy, a wealthy person

could repair to his or her closet. In the Renaissance, this was not the room for storing clothes or books or your grandmother’s sewing machine, but a small room like a study, used for reading or prayer. According to historian Mark Girouard, “it was perhaps the only room in which its occupant could be entirely on his own,” since servants would likely be present even in a bedchamber. Closets, and the solitude they represented, were at first an elite phenomenon, seen only in the houses of the wealthy. But, as Thomas Gyll shows, the idea of privacy actually did trickle down.

People of the middling and lower sorts

also participated in the “Great Rebuilding,” adding rooms to their houses where, eventually, they would seek to be alone.

These architectural changes are tied up with the development of privacy and the feelings of delicacy and shame we’ve linked to it. Some historians, such as Nicholas Cooper, suggest that “

evolving civility showed itself

in the desire for greater privacy and the need for more rooms”;

others reverse the causation

and see the increased number of rooms as creating spaces in which the modern notion of privacy could develop. Either way, privacy is inextricably linked to the advancing threshold of shame. Just as people started to wall themselves off physically from others in their new rooms, they began to wall themselves off psychically, as it were. Privacy created what we’ve seen Elias call “the invisible wall of affects,” and with it the embarrassment and shame at the sight or mention of bodily functions that medieval people lacked.

A solitary defecator from

The Metamorphosis of Ajax

. The motto

Sprinto non spinto

is perhaps best translated as “I go quickly, I don’t push or strain.”