Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (25 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

Herbert once burns a play

he receives “for the ribaldry and offense that was in it,” but scholars argue that he censored the play more for its “offense”—political satire—than for its bawdy language. Scholars argue that obscenity alone was not reason enough to ban a play in this period.

The first acknowledged case

of censorship on grounds of obscenity occurred a century later, with the prosecution of Edmund Curll in 1727. (He was accused of “obscene libel” and “disturbing the King’s peace” by publishing the pornographic novel

Venus in the Cloister

.) More often, Herbert links “ribaldry” with oath swearing, as in “oaths, profaneness, or obsceneness,” or “oaths, profaneness, and ribaldry.” These two kinds of bad language often appear together, and both must be avoided. In this respect, Herbert’s attitude is closer to the Victorian than to the medieval. In the Middle

Ages, we have seen, the sins of the tongue were numerous and varied, from scolding your neighbors to singing hymns of praise with too much expression. By the nineteenth century these “sins” have been narrowed down to two, which are almost constantly associated, as they are in Herbert’s record book—oaths and obscene language.

What best sums up the period’s mixture of oaths and obscenity, its shifting combination of Holy and Shit, is

a religious group from the 1650s

called the Ranters. Ranters are like witches—the popular imagination had a firm image of them, and many tracts were written that revealed their evil dealings, but it is unclear whether anyone actually self-identified as one. Ranters, it was thought, believed that God manifested himself in each individual believer; therefore, any impulse a person had was holy. It thus became impossible to sin, and the Ranters became the seventeenth-century id let loose. They had orgies, they masturbated in public, they kissed each other’s naked buttocks, they entered polygamous “marriages.” One of their songs prefigures the 1960s sentiment of “Love the One You’re With”:

The fellow Creature which sits next

Is more delight to me

Than any that I else can find;

For that she’s always free.

Equally shockingly, however, the Ranters also performed the Eucharist themselves, interrupted church services to preach their gospel, and swore. They were famous for their profane oath swearing, which they supposedly saw as the fullest realization of God in man. They swore so virulently that people who heard them were supposed to become prostrate with shock, as did one innkeeper who tried to throw a Ranter out of her house: “

it put the woman into such a fright

, to hear his curses and blasphemies, that she trembled and quaked some hours after.”

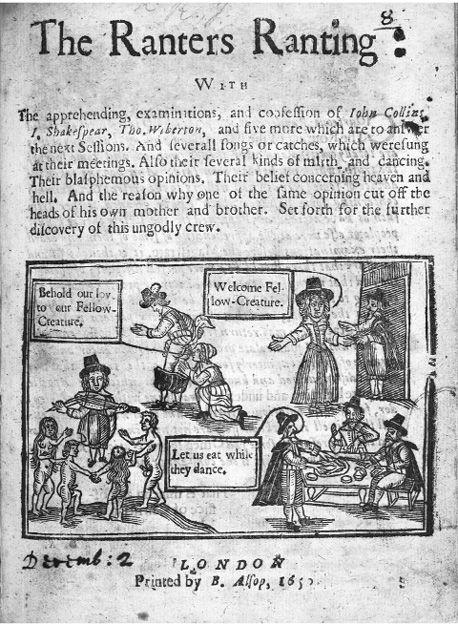

The Ranters Ranting

, 1650. This pamphlet details some of the Ranters’ horrible practices and helpfully illustrates them with a woodcut.

As the example of the Ranters indicates, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries presented a mix of the Holy and Shit. The Holy was declining in power, the Shit gaining it. Oaths had lost their ability to access God directly, and had begun to lose their power to shock and offend, but had not yet been eclipsed as the most powerful kind of language. Obscenity was beginning its rise to the position it has today, but it was still in the process of being defined, with obscene words sometimes avoided and sometimes ignored or even celebrated in the same contexts. It would take the extreme repression of the Victorians finally to secure obscene words their place as the “worst” in the English language.

Chapter 5

The Age of Euphemism

The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

In 1673, John Wilmot

, Earl of Rochester, composed a poem attacking his mistress for the criteria she used in choosing other lovers. While his subject matter perhaps fails to strike a chord, Rochester’s vituperative language is instantly recognizable. “Much wine had past with grave discourse / Of who Fucks who and who does worse,” he begins this poem, his most famous, “A Ramble in St James’s Park.” Drunk, and looking for some lechery himself, he wanders into the park, which is “Consecrate to Prick and Cunt” because it is so full of people meeting up for assignations. Even the trees are sexualized—their “lewd tops Fuckt the very Skies.” In this promiscuous landscape the poet sees his lover, Corinna, go off in a carriage with three fops, and complains:

Gods! that a thing admir’d by me

Shou’d fall to so much Infamy.

Had she pickt out to rub her Arse on

Some stiff prickt Clown or well hung Parson,

Each job of whose spermatique sluice

Had filled her Cunt with wholesome Juice,

I the proceeding should have praisd …

But to turn damn’d abandon’d Jade

When neither Head nor Tail persuade

To be a Whore in understanding

A passive pot for Fools to spend in… .

He is angry that Corinna has taken up with fools, though neither “head nor tail” inspired her choice—she was motivated by social snobbery, not intellectual interest or sexual desire. A good old country boy the poet could accept, or a parson with a large “spermatic sluice,” because the decision would be driven by pure desire. But when Corinna seduces the ridiculous men-about-town based partly on a calculation of social advantage, she becomes a whore, in the poet’s system of values.

Rochester concludes with one of the best curses ever:

May stinking vapours Choke your womb

Such as the Men you doat upon;

May your depraved Appetite

That cou’d in Whiffling Fools delight

Beget such Frenzies in your Mind

You may goe mad for the North wind,

And fixing all your hopes upon’t

To have him bluster in your Cunt,

Turn up your longing Arse to the Air

And perish in a wild despair.

May you go crazy, fall in love with the wind, stick your ass in the air, and die. It’s practically Yiddish, and a literal description of the Renaissance insult

windfucker

. This is followed by one of the best threats ever written down:

But Cowards shall forget to rant,

School-Boys to Frig, old whores to paint,

The

Jesuits

Fraternity

Shall leave the use of Buggery,

Crab-louse inspir’d with Grace divine

From Earthly Cod to Heaven shall climb,

Physicians

shall believe in

Jesus

And Disobedience cease to please us

E’re I desist with all my Power

To plague this woman and undo her.

Cowards will stop boasting, schoolboys will stop

boxing the Jesuit

, whores will stop putting on makeup, Jesuits will stop boxing the schoolboys, and genital lice will crawl from the scrotum up to heaven before the poet will stop tormenting Corinna for her lapses in amorous taste.

*

This is modern obscenity. Though some of the sentiments and language are foreign to readers today,

cunt, fuck, frig, prick, arse

, and other words are employed in order to provoke, to offend, to add insult to injury.

†

Rochester does not write “when your lewd Cunt came spewing home” because

cunt

is the most direct word for what he’s talking about and he values clarity of thought and expression. He uses it because it has become a derogatory, offensive, obscene word, and he wants to shock and offend.

Rochester’s poems heralded a brave new era of obscenity. Words such as

cunt

had been employed for hundreds of years, as we have seen, and in the Renaissance had begun to accrue the power being lost by oaths. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Holy and the Shit were mixed, neither one nor the other predominating. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, the balance swings entirely toward the Shit. Obscenities experienced a tremendous growth in strength, even as they disappeared almost entirely from public discourse. Obscene words for body parts and actions (sex and excrement) took oaths’ place as the words that shocked and

offended; that insulted; that expressed extremes of emotion, positive or negative. To a degree, obscene words even adopted oaths’ ability to signify the truth of a statement, a capability that harks back to the “plain Latin” of ancient Rome. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, obscene words began to be used nonliterally, for their emotional charge alone; at this point they completed their transformation into swearwords.

Rochester and his libertine companions were reacting to the Puritanism of the Commonwealth (1649–1660), when chastity, modest dress, and sober behavior reigned, except, of course, among the Ranters. When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, the merry monarch and his friends threw themselves into an opposite world—they wore beautiful clothes, took countless mistresses (one hopes it was on the basis of desire and/or intellectual interest), and practiced jolly pranks such as kidnapping heiresses and trying to marry them by force. (When he was eighteen,

Rochester abducted the fourteen-year-old Elizabeth

Malet from her grandfather’s coach. He was caught and sent to the Tower of London, and the girl was returned to her family. Elizabeth was apparently impressed—she married him of her own volition two years later.) After the riotous Restoration, however, a form of Puritanism came back, though its motivations were not religious this time, but social. The bourgeoisie developed in the eighteenth century—a middle class of merchants who seized on the “civilizing process” that had started in the Renaissance and made it their own. Good manners and refinement of language became an indication of social and moral worth, a sign of distinction that differentiated the middle classes from the great unwashed outside and below. Delicacy of speech and propriety of dress became increasingly important, to such a degree that chickens lost their

legs

and developed

limbs

(and later

white

and

dark meat

), lest the bird be so rude as to remind someone that people have legs too. These two trends account for obscenity’s great power in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Obscene words violated class norms—they were seen as the language of the lower classes, the

uneducated—and accessed the deepest taboo of Augustan and Victorian society, the human body and its embarrassing desires, which had to be absolutely hidden away in swaths of fabric and disguised in euphemisms.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English also needed to be purified to reflect the greatness of the growing British Empire. Latin had served Rome well; English had likewise to be made to conform to rules and shorn of slang (often code for obscenities) so that it could help to promote British imperialism and monumentalize the empire’s achievements forever. The growing empire paradoxically created the last category of obscenity—racial slurs. Many of these arose as cultures intermixed on a scale never seen before, as the empire stretched its arms across the ocean to America and then around the world, and the United States expanded westward.

From Oath to Affirmation

Vain and blasphemous oaths didn’t disappear all at once in the eighteenth century—theirs was a slow but steady decline, which is still going on today. In surveys of the American and British publics, oaths

are now ranked among the mildest

but most common swearwords.

In a 2006 study of speakers

of American English,

hell, damn, goddamn, Jesus Christ

, and

oh my God

were five of the ten most frequently used swearwords, with the top ten making up 80 percent of the swearing recorded.

Oh my God

alone accounted for 24 percent of women’s swearing.

*

In the early eighteenth century, vain and blasphemous oaths were even more numerous than they are today, as the obscenities were just starting to take their place in the lexicon of swearing. A character in Alexander Pope’s

The Rape of the Lock

(1712) provides an extreme but not unrealistic example of the way oaths were employed at this time: