Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (29 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

The newly wedded country gent

was registering at the Grand Pacific. The urbane clerk suggested the bridal chamber. Groom did not seem to take. The clerk again repeats his question, “Don’t you want a bridal chamber?” Countryman—Wall, you might send one up for her, I guess, but I can piss out the window.

A mid-nineteenth-century chamber pot, complete with poetry and brown frog.

The clerk, of course is suggesting the bridal room; the groom assumes he means the bridal chamber pot. Such a pot was also called a

jerry

, probably short for

jeroboam

, a large bowl, goblet, or wine bottle.

Commode

was also a popular euphemism, being French. A

commode

was originally any kind of elaborate and delicate piece of furniture with drawers and compartments. (It was also eighteenth-century slang for

a woman’s headdress, which at the time would have been a huge tower of real and false hair, feathers, ribbons, and powder—certainly also elaborate and delicate.) Its meaning narrowed to indicate a piece of furniture that could enclose chamber pots, hiding them from view, until finally it came to designate the pot itself. And

po

was in use by 1880—

pot

sounds so much decenter in French.

In the late eighteenth century, improvements in plumbing technology led to the wider adoption of flush toilets and a concomitant change in nomenclature. (John Harington, if you remember, had invented a flushing toilet in 1597 and wrote a mock heroic poem about it.) Flushing toilets, and the rooms they were in, began to be called

water closets

. Running water and ideas of cleanliness and hygiene later gave rise to

washroom

and

bathroom

, a masterpiece of misdirection, for, as British people love to point out to Americans, there is very often no bath involved.

Loo

, a common British word for

bathroom

, might also derive from the water component of the water closet. In Scotland, it had been polite to cry “Gardy-loo” when emptying your chamber pot out the window, a corruption of

gardez l’eau

—“watch out for the water.”

Loo

might also be a corruption of the French for “place,”

lieu

, as in

place of easement

. One final candidate etymology has

loo

coming from

bourdalou

, a portable chamber pot for ladies. The seventeenth-century French preacher Louis Bourdaloue was so popular that people would assemble hours in advance of his sermons. Ladies brought their

bourdalous

, which they could use under their skirts, so that they didn’t have to lose their seats by getting up to find the privy. (Bourdaloue often preached at Versailles, so the ladies very likely would have had trouble finding a privy anyway. The palace was plagued by people defecating in the corners of rooms and urinating into potted plants, fireplaces, staircases, etc., perhaps out of carelessness, perhaps from a lack of privy-cy.)

Latin makes its contribution to toilet words with

lavatory, latrine

, and

urinal. Lavatory

is like

washroom

—in the Middle Ages it had referred to a vessel for washing the hands, and

came to indicate

the

room in which you wash your hands, because you’ve just used the toilet.

Latrine

, like

lavatory

from the Latin for “wash,” has always referred to a privy or set of privies in a camp, barracks, or hospital.

Urinal

was a glass used by medieval physicians to collect urine for examination, and also by the fifteenth century a plain chamber pot. By the mid-nineteenth century it had attained the meaning it has today—a fixture attached to a wall, used by men for urinating (or a room containing such fixtures).

Finally we go back to French for the most common toilet word,

toilet

itself. It originated in the French word

toilette

, meaning “little cloth.” The

toilette

covered the dressing table while makeup was applied and hair was coiffed; eventually it came to stand for the articles on the dressing table used in grooming, then the process of getting dressed. From there, it came to refer to the room in which the getting dressed happened, which was often furnished with a bath. Hence, as can be seen in the

OED, toilet

came to indicate a bathroom, a lavatory, and then the ceramic pedestal itself.

In American English, the euphemism treadmill has turned for

toilet

, and it has now become a vulgar word instead of a decorous one used to disguise an unpleasant fact of life. Polite Americans would be hard-pressed to ask “Where’s the toilet?” as is commonly heard in Britain. In Britain, though,

toilet

is vulgar in the original sense of the term—it has class connotations, employed by people of the middle class on down.

Loo

is the word used by upper-class Brits. In a reflection on social class that he composed for the

Times

of London, the Earl of Onslow admitted that “

I find it almost impossible

to force the word toilet between my lips.” (He found it impossible to spell as well, going for the French

toilette

.) And when Prince William and Kate Middleton broke up briefly in 2007, the British press blamed it on Kate’s mother’s use of the word

toilet

, creating a scandal called, not surprisingly, “

Toiletgate

.” The prince could never marry a girl whose mother said “toilet” (and did other irredeemably middle-class things such as chew gum and say “Pardon?” instead of “What?” or “Sorry?”). Toiletgate fizzled out, of course—the prince married his

commoner, and Mrs. Middleton probably now makes sure she uses the facilities before she goes out.

These are, believe it or not, just a few of the more popular euphemisms for

toilet

that were in use in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, showing how misdirection, Latin, and French allowed English-speakers to create new, polite words that allowed them to discuss things they were not supposed to mention. To be fair, there were also dysphemistic names for toilets, words intended to make a thing sound worse than it is.

Shit-house

first appeared in 1795, according to the

OED

, while

bog-house

was popular in the eighteenth century, ceding ground to the shortened form

bog

in the nineteenth. (There was also a brief flowering of

boggard

in the seventeenth century.) The

bog

- words evidently derive not from

bog

in the sense of “wet, swampy ground” but from a verb meaning “to exonerate the bowels; also

trans

. to defile with excrement” (another one of those “to spray someone or something with shit” verbs, which we no longer seem to need today). In its definition, the

OED

makes clear that

bog

in this sense is not a polite word—it is “a low word, scarcely found in literature, however common in coarse colloquial language.”

John

started to compete with

jakes

as the masculine name of choice for the facilities in the eighteenth century—a 1735 list of rules for students at Harvard College includes the biblical dictum that “

No freshman shall mingo

[piss] against the College wall or go into the fellows’ cuzjohn.” “Cuzjohn” is “cousin John”; the word is still in use as just plain

john

and remains mostly an Americanism.

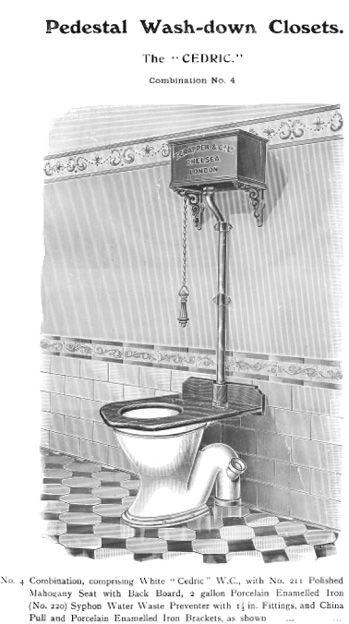

Crapper

, another dysphemistic use, is almost unique in the realm of bad words in that it is the subject of an etymological legend that turns out to be (mostly) true. The story is that a man named Thomas Crapper invented the flush toilet, and that it is called “the crapper” in his honor. There was indeed a Thomas Crapper (1836–1910), and while he did not invent the flush toilet, he did manufacture them and patent many improvements to the design, always printing his name boldly in his bowls and on his cisterns.

Crap

itself is an old word, first appearing in the fifteenth century and indicating “the husk of grain, chaff.” By the Victorian era, it had developed its contemporary meaning of bowel exoneration, the process or product, but was used mostly in America. Simon Kirby, managing director of Thomas Crapper & Co. Ltd.—which is still in business today—explains how the vulgar American word and the venerable English plumber collided to give us “the crapper”: “

During World War I

, American servicemen stationed in London were so amused that the ancient and vulgar word for faeces was printed on so many water closets, that they began to call the W.C. a ‘crapper.’ Though crude, the soubriquet made sense and it stuck… . In etymological circles, this process is called ‘back formation,’ which sounds rather like a sewer problem!”

Crapper model #4, “The Cedric.”

Alternatively, one could take the Roman view and see it as nominative determinism (“Nomen est omen”)—Thomas Crapper was destined to work with toilets, just as much as

A. J. Splatt and D. Weedon

(“wee’d on”) were fated to publish an article on urinary incontinence (“The Urethral Syndrome: Experience with the Richardson Urethroplasty”), or Usain Bolt to become the fastest man alive.

Class and Swearing

Euphemisms enjoyed such prominence because the eighteenth and especially the nineteenth centuries were the age of decorum. The civilizing process that began slowly in the Middle Ages reached its height during these years; the shame threshold was at its widest extent. Bodily functions that formerly were performed unashamedly in public were now done only behind closed doors; the same functions had been discussed openly but were now subject to a parallel cloaking in language. As one historian writes, “

Excretion was an accepted and semipublic event

that Chaucer rarely used for comedy. In the last [i.e., nineteenth] century, these body functions have become rites performed in the shamefast privacy of a closed room, the excreta being immediately laved away by sparkling rivulets, to be seen and smelled no more.” Likewise, the words used to discuss

these topics were washed out of public discourse—

shit

became

defecate

, and Victorian readers were embarrassed by the use of

piss

in the King James Bible. All things sexual were hidden away to an even greater degree, including things such as trousers that were not themselves taboo but lay adjacent to taboo areas.

The newly emerged middle class was responsible for a great deal of this increased delicacy. The biggest social change of the eighteenth century was the development of the bourgeoisie—historical linguist Suzanne Romaine observes that “

the transition from a society of estates or orders

to a class-based society is one of the (if not

THE

) great themes of modern British social history.” In the Middle Ages, society had been rigidly hierarchical and divided by social function—those who fought (the landed gentry and knights), those who studied and prayed (the clergy), and those who worked (the peasants). You could go from the gentry to the clergy—many second and third sons did exactly this in England, because primogeniture left them little to inherit—but otherwise social mobility was almost impossible. In the Renaissance, merchants and craftspeople began to be seen as “the middling sort”—they were not noble, but neither were they poor peasants. By the eighteenth century, the industrial revolution, colonization, and global trade had made many of the middling sort extremely rich, forcing a reevaluation of their place in society. Economic criteria replaced social function as the determiner of social status, giving us what was coming to be called “class,” the upper, lower, and middle. Since class membership was determined to a great extent by money, class boundaries were much more fluid than those between the old estates. As one’s power, wealth, and influence increased, one moved up; if one went bankrupt, one moved down. The upper classes were more or less secure, with their ancestral lands and titles, but the middle classes felt themselves to be in a constantly precarious position. They needed to shore it up by broadcasting their differences from the lower classes—they moved to the suburbs, behaved with what they saw as greater moral probity, and, most relevant to us, spoke differently. “

The middle class … sought an identity

for themselves

predicated in asserting their social and moral superiority over the working classes,” as linguist Tony McEnery puts it. They strove to “establish a personal ascendancy above the herd as right minded, responsible and successful citizens, and at the same time to impress their worth upon their social betters, including God.”