Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (28 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

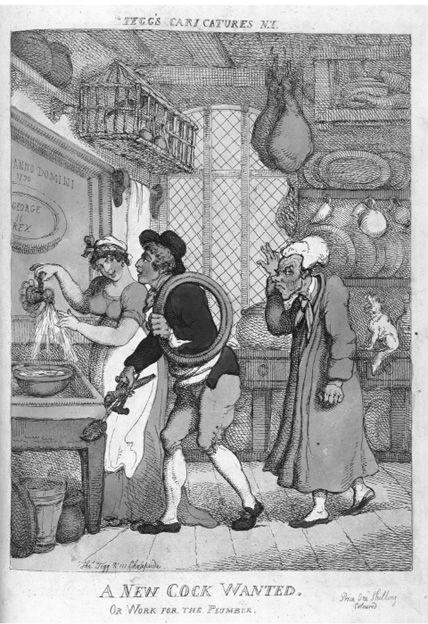

Several widespread Victorian assumptions about language are crystallized in this account. Marryat associates euphemisms with women, and with women of a particular social class—the middle. Such women, like the mistress of the seminary, see delicate language as a way to advertise their delicate sensibilities, which are themselves supposed to be an indication of social and moral worth. Marryat is also poking fun at these women who cannot bring themselves to say

leg

, and this is a perennial theme—Victorian euphemisms went hand in hand with a discourse that ridiculed them.

There is scholarly debate about the number

of people who really sewed inexpressibles for the limbs of their pianos, or whether Marryat’s seminarian was an exception or even his invention. But it is hard to deny that such coverings are the logical consequence of the thought process that led society to deem trousers and legs as beyond the pale. Marryat’s story reveals something about Victorian society, even if most people chose to show off, rather than cover up, the ornately carved legs of their mahogany furniture.

Marryat’s account also makes clear that he sees

limb

as an American euphemism. He, “having been accustomed only to

English

society,” would use the more straightforward word

leg

. In fact, many nineteenth-century Brits thought that euphemism was a particularly American affectation. They pointed out that while Americans talked about their

roosters

and

faucets

, Brits still had

cocks

in their barnyards and bathrooms. While Americans picked at the

bosom

of a chicken, Brits tucked heartily into the

breast

. The Englishman Thomas Bowdler censored Shakespeare in 1807, but the American Noah Webster castrated the Bible itself in 1833, inserting “

euphemisms, words and phrases

which are not very offensive to delicacy, in the place of such as cannot, with propriety, be uttered before a promiscuous audience.” (

Promiscuous

may seem like an unfortunate adjective to choose when one’s project is to get rid of “language which cannot be uttered in company without a violation of decorum, or the rules of good breeding,” but in 1833 the word meant “wide and diverse,” not “sexually indiscriminate.” It attained its current meaning only in the late nineteenth century.)

Even John Farmer and William Henley

, authors of the magisterial 1890–1904 slang dictionary that contains thousands of euphemisms, accused Americans of being overly euphemistic. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s use of the word

benders

for

legs

prompts a series of recriminations from them:

bender

is “a euphemism employed by the squeamishly inclined for the leg. A similar piece of prudishness is displayed in an analogous use of ‘limb.’ With a notorious mock-modesty, American women decline to call a leg a leg; they call it a limb instead… . Sensible people everywhere, however, have little part in such prudery.”

Why Americans say

faucet

.

But there were plenty of people willing to bemoan the British affection for euphemism too, and plenty of examples to give them cause.

In the 1874 edition of his

Slang Dictionary

, John Hotten took issue with British euphemism, condemning words such as

inexpressibles

—which were as British as meat pies and orderly queues—as “affected terms, having their origins in a most unpleasant squeamishness.” Henry Alford, dean of Canterbury, noted biblical scholar, and editor of John Donne, had much to say about the evils of euphemism in his

Plea for the Queen’s English

. “

In the papers

,” he complains—newspapers are in his view responsible for much of the euphemistic inundation—“a man does not now

lose his mother

: he

sustains

(this I saw in a country paper)

bereavement of his maternal relative

.” No one

goes

anywhere anymore—a man going home is set down as “an individual proceeding to his residence.” Nor does anyone

eat

when it is possible to

partake

, or

live in rooms

when the option is to

occupy eligible apartments

.

Some of Alford’s complaints are not about euphemisms per se but about an overly inflated style, diction that has come to be known, probably to Alford’s shame, as “Victorian.” It is not particularly Victorian, either—Alexander Pope had already been calling fish “finny prey” and the “scaly tribe” in the early eighteenth century. When Alford complains about

partake

, he is objecting not to a euphemism for

eat

, but to an ameliorative term, a word with more or less the same meaning that is employed because it is more formal, more elevated—fancier. (Actually, as Alford points out,

partake

is not a synonym for

eat

. It means “to share in something,” whether food, a military expedition, or a joint visit to the privy.)

Proceed

was likewise an ameliorative term for

go

—it makes the ordinary act sound better. The line between euphemisms and ameliorative terms is thin and hard to keep to, however—both serve the same purpose of substituting for a word or disguising a topic that is too vulgar, or sometimes just too ordinary, for the context.

Even the pornography of the period embraced this elevated style. In 1749, John Cleland wrote his way out of debtor’s prison with a pornographic novel that contained not a single obscene word.

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

(

Fanny Hill

) is basically a series of sexual encounters between Fanny and various men, other women and various men, Fanny and various women, other women and various women, and, once, two men. A typical scene has Fanny taking revenge on her own unfaithful lover by seducing a young man with a huge “machine,” who is so “full of genial juices” that he can orgasm twice in a row:

Not once unsheathed

, he proceeded afresh to cleave and open himself an entire entry into me, which was not a little made easy to him by the balsamic injection with which he had just plentifully moistened the whole internals of the passage. Redoubling, then, the active energy of his thrusts, favoured by the fervid appetency of my motions, the soft oiled wards can no longer stand so effectual a picklock, but yield and open him an entrance.

This passage is actually about Christ’s love for his Church. No, not really. It does use the biblical metaphor of sex as opening a locked door, though.

A surprisingly large number of other authors went for “botanical porn,” which involved learned comparisons of the genitalia to plants. Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, was one such author, who produced the only very mildly titillating

The Loves of the Plants

in 1789. Other botanists were more explicit than Darwin, but always in the most refined of language. The author of a mid-eighteenth-century poem called

Arbor Vitae

(“

The Tree of Life

”) describes the tree this way:

The tree of Life, then, is a succulent plant, consisting of one only stem, on the top of which is a

pistillum

or

apex

, sometime of a glandiform appearance, and not unlike a May-cherry, though at other seasons more resembling the Avellana or filbeard tree. Its fruits, contrary to most others, grow near the root; they are usually two in number, in size somewhat exceeding that of an ordinary nutmeg, and are both contained in one Siliqua, or purse, which together with the whole root of the plant, is commonly beset with innumerable fibrilla, or capillary tendrils.

If you don’t recognize this as a description of the penis, you haven’t been paying attention.

Fanny Hill

and works of botanical erotica contain obscene subject matter—almost nothing

but

obscene subject matter, in fact—without offensive or low language. They are porn with pretensions, the product of an age with a craze for euphemisms, an era that prized delicate and learned diction whatever the occasion.

Euphemism is the opposite of swearing. Swearwords work because they carry an emotional charge derived from their direct reference to taboo objects, orifices, and actions. Euphemisms exist to cover up those same taboos, to disguise or erase the things that prompt such strong feelings. These anti-obscenities, if you will, are

formed by several processes, including indirection, Latinization, and employing French. A word such as

inexpressibles

works as a euphemism because it completely disguises the thing to which it refers—it hides its referent, as do

confinement, situation

, and

condition

(“interesting” or otherwise), which were popular Victorian euphemisms for

pregnancy

. Latin, with its irreproachable reputation as the dead language of the well educated, also gave rise to many euphemisms. In the Renaissance, a man could freely piss in public; now he had to

micturate

(c. 1842) behind closed doors. Other bodily functions got Latinized as well, and so we have

defecate

(to shit),

osculate

(to kiss),

expectorate

(to spit), and

perspire

(to sweat).

Of perspiration

, the

Gentleman’s Magazine

of 1791 records: “It is well known that for some time past, neither man, woman nor child … has been subject to that gross kind of exudation which was formerly known by the name of

sweat

; … now every mortal, except carters, coal-heavers and Irish Cahir-men … merely

perspires

.”

Linguists Keith Allan and Kate Burridge

call Latinate terms such as these

orthophemisms

rather than

euphemisms

. Orthophemisms are “more formal and more direct (or literal)” than euphemisms.

Defecate

, because it literally means “to shit,” is an orthophemism;

poo

is a euphemism, and

shit

is a dysphemism, the taboo word the others were created to avoid. According to Allan and Burridge, both euphemism and orthophemism arise from the same urge: “they are used to avoid the speaker being embarrassed and/or ill thought of and, at the same time, to avoid embarrassing and/or offending the hearer or some third party. This coincides with the speaker being polite.”

French also contributed a number of popular euphemisms, including

accouchement

for having a baby,

lingerie

for underwear, and

chemise

for

shift

, a word that itself had replaced the even more indecent

smock

(which is a long dress or shirt that served as an undergarment). The poet Leigh Hunt recorded his difficulties in finding a title for his version of a medieval story about a knight who fights in a lady’s chemise to prove his valor. He attempted to call it “The Three Knights and the Smock” or “The Battle of the Shift,” but

public outcry forced him to expunge any mention of the offending clothing. He marveled that he could not even employ the word

chemise

—“

not even this word, it seems

, is to be mentioned, nor the garment itself alluded to, by any decent writer!” Hunt eventually called the 1831 poem “The Gentle Armour.” As late as 1907,

shift

was a powerfully taboo word.

When an actress spoke it

onstage during the premiere of John Millington Synge’s

The Playboy of the Western World

, the audience began to riot. The play is about life in an isolated village in Ireland, and premiered in Dublin at the National Theater; in these circumstances, the use of

shift

was seen as an insult to Irish Catholic womanhood. A decent woman would not be mentioning her unmentionables at all, let alone using the vulgar word

shift

.

Let’s focus now on one taboo area to show the great range of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century euphemisms, and how our three drivers—misdirection, Latin, and French—team up in creating them.

Consider the toilet

. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,

house of office

was still in common use, thanks perhaps to its entirely mystifying literal sense.

House

was also involved in a number of related euphemisms, such as

necessary house, house of commons

, or just

commons

—a haven of democracy to which everyone had to resort, rich or poor, male or female, old or young.

*

There was also the less frequently employed

mine uncle’s

(house). Chamber pots were still employed for relieving oneself in the middle of the night, or when suffering a disinclination to proceed to the privy, and continued to be called

chamber pots

, or just

chambers

. This shortening occasions a joke in the Victorian collection of erotica

The Stag Party

(ca. 1888, edited by the American author of children’s verse Eugene Field, most famous for

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod

):