Homo Mysterious: Evolutionary Puzzles of Human Nature (40 page)

Read Homo Mysterious: Evolutionary Puzzles of Human Nature Online

Authors: David P. Barash

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Science, #21st Century, #Anthropology, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Cultural History, #Cultural Anthropology

At the same time, it is not that easy to discount the various group-level payoffs that may be associated with religion, if only because religion is such a group-oriented phenomenon, whose practitioners often experience a fervent sense of togetherness. And for a social species such as

Homo sapiens

, togetherness is itself a powerfully satisfying experience, just as social isolation can be terrifying. When given the choice, few resist the promise—as stated in the song from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Carousel

—that “You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

Maybe the personal payoff of religious devotion (the satisfied sense of spiritual and existential fulfillment that so impressed William James) serves as a proximal mechanism getting people to participate, in return for which they gain the various social and evolutionary benefits. Just as hunger gets us to eat, which ultimately nourishes the body, perhaps evolution has outfitted human beings with a spiritual hunger, which induces them to follow one religion or another, as a result of which they experience less personal loneliness, fewer doubts, and greater efficiency in their daily lives.

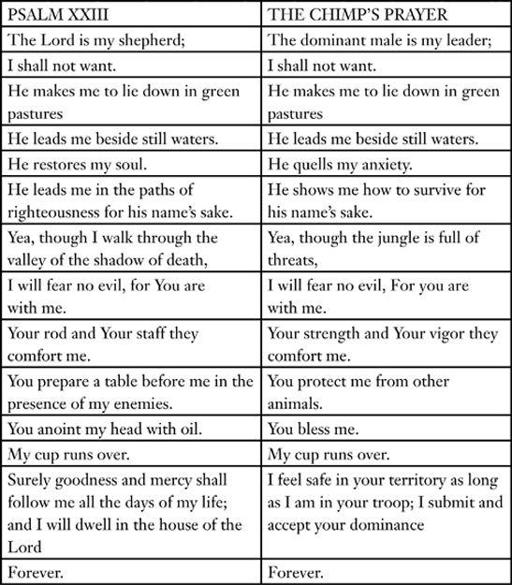

It is also possible that religious belief—and particularly, faith in one or a small number of very powerful deities—derives from a this-worldly primate tendency to worshipfully obey a dominant leader. Jay Glass has made the interesting argument that “In the original state of nature, for both animals and humans, loyalty to a Supreme Being (aka dominant male, king, warlord, etc.) offered protection from enemies and provided the necessities to sustain life. Those that did not put their faith and trust in a god-like figure did not survive to produce the next generation.”

9

The jewel in Glass’s argument is his reworking of the 23rd Psalm, as it might

describe members of a chimpanzee troop speaking of the dominant male:

This rendering overstates the degree of affiliation between “average” chimp and dominant male(s), but it nonetheless deserves more attention than it has received.

vii

Nonetheless, monotheism isn’t universal, nor is worship of male god(s)—both of which are implied by Glass’s thesis. Thus, his book,

The Power of Faith

,

overstates the role of the dominant male as leader of the pack, not only in animal societies, but in human religion as well. It also focuses too intently on chimpanzees, omitting, for example, bonobos, which may if anything be more closely related to

Homo sapiens

, but among whom dominant males are something of an oxymoron.

In addition, it seems likely that insofar as a primate troop member “worships” his or her leader, at least the existence of that leader is undeniable, along with (in most cases) the negative consequences of deviation. On the other hand, to my knowledge, God seems on balance less likely to strike down disbelievers than a dominant animal is to punish would-be rebels. Disbelief in God thus seems less costly (at least in the short term) than is failure to honor and obey one’s flesh-and-blood leader. Yet, as we shall soon consider, it is also possible that religion has established and maintained itself precisely by exacting temporal punishment against apostates, which not only harkens back to Richard Dawkins’s hypothesis of religious belief as parasitic meme but also provides a potential mechanism whereby religion could conceivably be selected for at the level of groups.

There seems little doubt, in any event, that numerous payoffs can be derived by followers of religion no less than those following a dominant, secular leader, who participate in a group whose shared followership results in greater coherence and thus enhanced biological and social success.

One such payoff was glimpsed by historian Walter Burkert, who argued that religion helps induce people to make a last-gasp effort when otherwise they might stop trying. “Although religious obsession could be called a form of paranoia,” wrote Burkert,

it does offer a chance of survival in extreme and hopeless situations, when others, possibly the nonreligious individuals, would break down and give up. Mankind, in its long past, will have gone through many a desperate situation, with an ensuing breakthrough of

homines religiosi

.

10

On the surface, this seems plausible, but it begs a crucial question: If religion has proven adaptive because it evokes greater confidence, increased effort, or enhanced probability of a last-gasp attempt that occasionally yields success and thus increases fitness, why aren’t people primed to make such efforts in any event, without religion no less than with it? The issue raised is similar to the mystery of the placebo effect, encountered earlier. Thus, if believing in something (the efficacy of a medicinal cure, the prospect of divine intervention on the battlefield or in response to a final, last-gasp effort) contributes to success, then why the necessity of belief? Wouldn’t selection favor bodies curing themselves via those immunologic mechanisms that are evidently already available, or people making other efforts on their own behalf—even without much prospect of success—regardless of whether they were motivated to do so by religious faith?

There is also a converse of making extra efforts because of religious conviction: remaining calm in the face of disaster. Here is Zora Neale Hurston’s description of the Okeechobee Hurricane and its resulting flood of 1928:

Ten feet higher and far as they could see the muttering wall advanced before the braced-up waters like a road crusher on a cosmic scale. The monstropolous beast had left its bed. Two hundred miles an hour wind had loosed its chains. … [T]he wind came with triple fury and put out the light for the last time. They sat in company with others in other shanties. … [T]hey seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.

Most likely, the extra effort and don’t panic hypotheses don’t hold water with regard to individuals, since selection should indeed favor making that extra effort and/or avoiding panic any time the ultimate benefit—to the individual—exceeds its cost. However, let’s imagine that making the “ultimate sacrifice” is indeed counter-evolutionary … for the individual. It could nonetheless be beneficial for the group. So, selection could possibly operate to favor religious conviction, if it worked at the group level, in which case Burkert’s extra effort hypothesis might provide some biological momentum. Similarly, if it is beneficial to avoid panic, then people should have been selected to do so, without any necessary prod from religion. But maybe “watching God” under times of

severe stress helped provide the kind of preservative pause that was adaptive after all.

There’s more. The evolution of religion could be linked in a curious way to the evolution of consciousness. As our ancestors evolved consciousness (see

Chapter 9

), they may well have become increasingly aware—consciously, for the first time in the history of life on this planet—that they had personal interests that didn’t necessarily coincide with the social norms and traditions of their social unit. Groups function better, with less friction and more cohesiveness, when their members don’t lie, steal, or murder (also, of course, when they don’t covet their neighbor’s wife, and so forth). But individuals are often inclined to do precisely these things, and more. In the absence of consciousness, such inclinations are likely to be acted upon, whereas once individuals become aware of their own selfish propensities and sensitive to the drawbacks they pose to the “greater good,” the stage could be set for explicit statements of social prohibitions and expectations, and for people’s willingness—however reluctantly—to go along.

Early human beings’ emergent awareness of their own selfishness, although beneficial to the individuals in question, would have been detrimental to the group, insofar as it would have induced them to be less reliable “team players.” It is at least possible, therefore, that groups responded by seeking to establish supraindividual norms—enforced via what we now call religion—which were then imposed on otherwise rebellious individuals: “Do these things, even if you’d rather not, because God commands it,” while at the same time, the group benefits.

The above considerations add cogency to Voltaire’s celebrated observation that if God didn’t exist, we’d have to invent him—in order to reap some of the payoffs that religion provides. Can we carry this a step further and conclude that if God didn’t exist, natural selection would have had to evolve Him … if not for the good of the participating individual, then for the benefit of the greater group?

There is a common denominator uniting the various hypotheses we have just considered, namely, that religious commitment involves forswearing certain personal gains while benefiting other individuals. Insofar as this basic pattern has contributed to the evolution of religious belief and practice, then the puzzle of religion’s origin corresponds with another puzzle: the evolution of altruism. Darwin struggled with this matter, asking how selection could favor traits that helped others while harming those who manifested those behaviors. He concluded that

A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection.

Even Darwin was occasionally wrong, and this appears to be one such case. The process he described above would not be “natural selection,” but its close cousin, group selection. Natural selection is defined as “differential reproduction,” leading to the crucial question, “Differential reproduction of what?” Biologists understand that the fundamental units of natural selection are individuals and—more precisely yet—their constituent genes. Differential reproduction

of groups

, on the other hand, is a different matter, and one that is highly contentious among evolutionists.

This is an important matter, deserving a brief detour, both because it highlights an interesting scientific debate in general and because it goes to the heart of the hypotheses we have just been discussing for the evolution of religion. It is tempting to think that natural selection works to promote the success of groups, especially when these groups compete with each other. If individuals could somehow be persuaded to give up their interest in maximizing their personal reproductive success and instead agree to subordinate some of their selfishness to the overall greater good, then the groups of which they are members would do better as a result, whereupon the constituent individuals would do better, too.

Shouldn’t they give up a bit to get even more in return? And shouldn’t such a tendency be favored not simply by ethical appeal to the human conscience, but also by the hard-wiring of natural selection?

In most cases, the answer is no.

This is because even though self-sacrifice might help groups do better in competition with other groups, it would necessarily mean that

within

their groups, altruists would be worse off than selfish individuals who refused to go along. Economists call it the “free-rider problem,” experts in game theory talk about “defectors” or “cheaters,” while for biologists, it’s a matter of self-interested individuals enjoying a higher fitness than their more selfless, group-oriented colleagues. Even if groups containing altruists—whose altruism might incline them to share food, sacrifice themselves in defense of others, and so on—are better off than are groups lacking altruists, the problem is that those altruistic food sharers and other-defenders would be trumped by free-riders, defectors, and cheaters who selfishly looked out for number one.

Mathematical models have demonstrated that whereas altruism could, in theory, evolve via group selection, the constraints are very demanding. Among other things, the difference in reproductive success between altruists and selfish cheaters would have to be quite low, whereas the disparity between groups containing altruists and those lacking them would have to be very high—and in actuality, the opposite is typically true. It makes a big difference whether you are a self-sacrificing, group-oriented altruist or a selfish, look-out-for-number-one SOB. Moreover, although the differences between successful and less successful individuals is likely to be very great, disparities in the reproductive rates of groups are likely to be much more sluggish. Not surprisingly, no clear examples of group selection among nonhuman animals have been identified.

On the other hand, things just might be different when it comes to

Homo sapiens

.

11

Compared to other creatures, our own species is extraordinary in the degree to which we stick our noses into each other’s business: snooping; gossiping; wondering who is doing what and when; who is toeing the line and who is shirking; who said what to whom; who attended church, synagogue, mosque, or the ritual fire dance and who stayed home; who sacrificed a goat

and who held back; who engaged in the expected observances and who deviated from the rules.