Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II (16 page)

Read Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II Online

Authors: Laurence Rees

Previous page

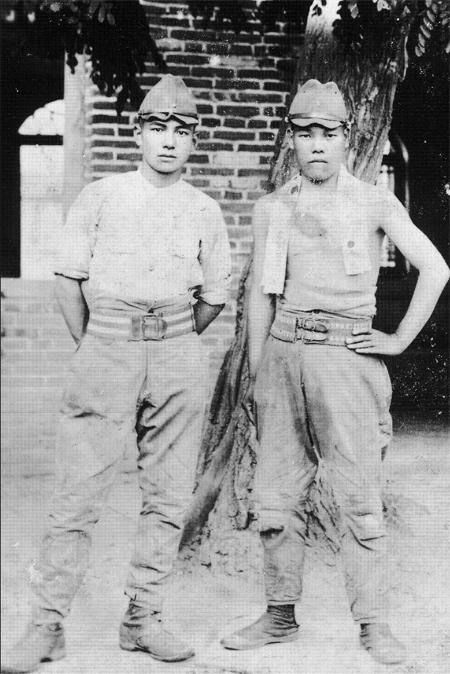

Japanese soldiers after capturing a Chinese village in the summer of 1938.

The world knew of the Rape of Nanking six months before — much less publicized were the atrocities committed by the Imperial Army in the campaign that followed.

Above

British soldiers captured after the fall of Singapore in February 1942.

Seventy thousand British and Allied soldiers became prisoners of the Japanese in the largest surrender in British military history.

Below

Allied prisoners of war en route to a Japanese prison camp.

Above left

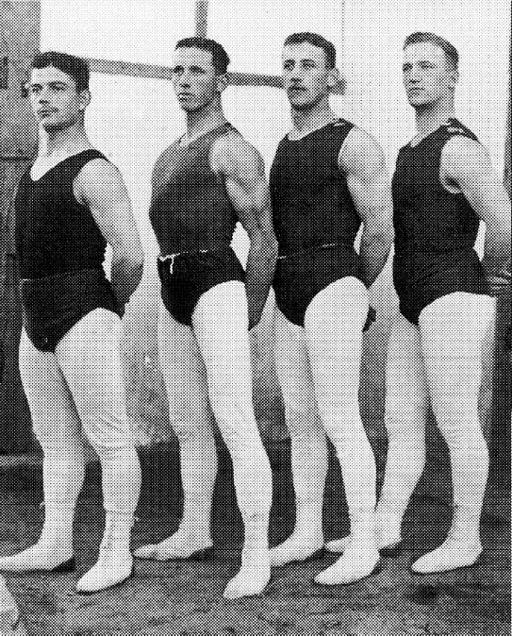

German prisoners of war held by the Japanese during the First World War.

These soldiers, humanely treated by their Japanese captors, are dressed for gymnastics.

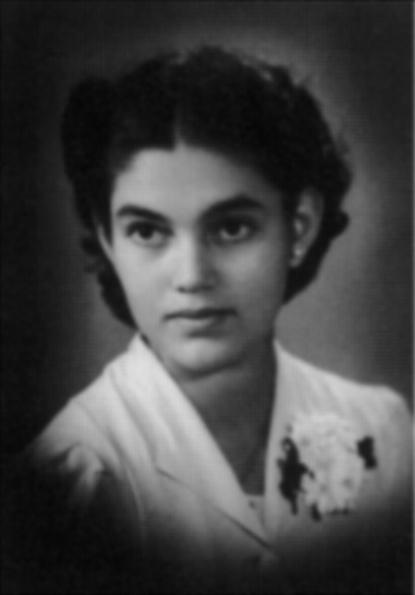

Below left

An Allied soldier after years of captivity during the Second World War.

Right

A civilian internee in Stanley Camp, Hong Kong, displays the daily rations for five people, her own emaciated body further proof of the dearth of food in the camp.

Above

An allied air reconnaissance picture of Sandakan prisoner of war camp in northern Borneo.

Below

The graves of some of the 2500 Allied POWs who perished at Sandakan, either dying on the forced march through the jungle, at the camp itself, or after they finished the trek.

Opposite

Bill Hedges (left), a corporal in the Australian Army.

He fought the Japanese in New Guinea, and found dear evidence of the cannibalism practised by the Imperial Army.

Above

The aftermath of the Japanese attack on the American naval air station at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

Below

More destruction after what Roosevelt called ‘the day of infamy’ — American warships lie wrecked at Pearl Harbor.

LURCHING TOWARDS DEFEAT

T

he war turned quickly for the Japanese.

Just four months into the conflict, the Japanese High Command witnessed disturbing signs that they had fundamentally misjudged the power and resourcefulness of their enemy.

In the early hours of 18 April 1942 Colonel James Doolittle of the United States air force led sixteen B-25 bombers on raids on Tokyo and several other Japanese cities.

Launched from an aircraft carrier in the Pacific the planes had to fly over Japan, drop their bombs and then land at airfields in China controlled by the Chinese Nationalists.

The bombing was a symbolic morale-boosting gesture by the Americans — and it caused consternation in Japan.

How was it possible that their proud capital city, the home of the divine emperor himself, could be subjected to an American air raid?

Never in Japanese history had an enemy struck the homeland in such a provocative way.

The response of the Japanese government to this humiliation was hugely significant.

Eight of the American pilots were captured when their B-25s were shot down over Japanese-controlled regions of China.

They were immediately sentenced to be executed because, it was deemed, they had committed a war crime.

(The Imperial Army appear not to have appreciated their own double standard in this regard — the Japanese had, of course, been bombing civilians in China for many years.) Even though prime minister Tojo was against the executions at first, he was swayed by the views of his senior military commanders, all of whom wanted the fliers killed.

Hirohito stepped in and personally commuted five of the death sentences.

Eventually, three of the Americans were executed.

The Doolittle incident is important because it demonstrates both the lack of foresight of the Japanese government (had they never thought Japan might be bombed?) and their misjudged response once they had captured the Americans.

The High Command clearly felt that if the B-25 pilots were executed it would deter future raids.

Similar thinking had led the Japanese to believe that a sharp defeat at Pearl Harbor would cause the United States to be circumspect in its subsequent dealings with Japan.

It was a colossal error of judgement, which revealed the profound ignorance of the High Command about how Western nations were likely to respond to Japanese aggression.

Pearl Harbor had sparked the fire of American anger, and the execution of the pilots from the Doolittle raid fanned it still further.

(It is also interesting to note that Hirohito was never held to account by the Americans at the end of the war for his decision

not

to commute the death sentences on the three pilots who were executed — it is hard to imagine how a Nazi leader who acted in a similar way would have escaped punishment at the hands of the Allies.)