Horse Lover (19 page)

I could feel Sarah’s pain. My mind raced, trying to think of the right words to offer my daughter. “Look, Sar, you know the hunter classes are beauty competitions. A pretty horse and rider with correct postures wins. You’re entered because they’re good preparation to get your jumping form right. But you went up there not expecting to win the hunter classes.” Sarah sniffled in agreement. “The second week is the jumping competitions. I’m here to tell you that you’re well mounted. Squaw is good in the large pony classes and Blondie absolutely excels in the open jumping. So you’re going to have to bide your time until the jumping classes start. Hold your head up during the hunter contest and don’t worry about the shiny horses winning. Your turn will come in the jumper division. That’s the place where it matters how high you can go and how fast you can do it. Blondie and Squaw gave you their trust long ago and they’ll come through for you. Just watch.”

“Okay, Dad.” Sarah’s voice sounded a bit calmer. “I won’t worry about the hunters.”

“After it’s all over, we’ll have another conversation and I bet you’ll see things differently.”

16.

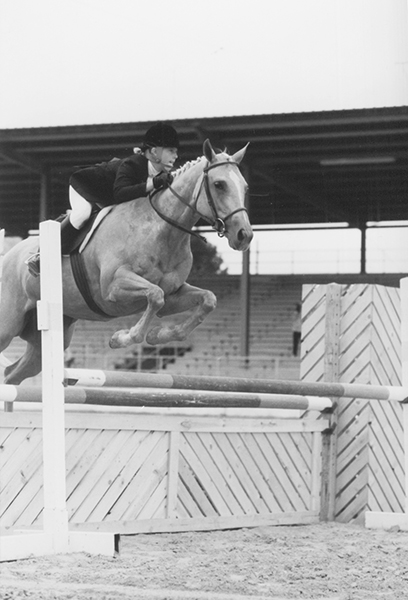

Sarah and Blondie competing

The next evening the phone rang again. This time it was Sue. She was not a happy show mom. That morning, she and Sarah had driven the horses the eight miles to the show grounds. When the old trailer bounced across a set of railroad tracks, its floorboards ripped loose and fell to the pavement. Neither Sue nor Sarah was aware anything was amiss behind them. The only thing left to hold up the horses was the angle iron that held the boards. Fortunately, Blondie and Squaw’s ranch survival skills kicked in and they managed to find some footing. If they hadn’t, they would have fallen through to the pavement and been dragged along, even killed. I felt like a damn fool. What was I thinking when I bought that trailer? By the time Sue vented on me, she had already had the boards replaced.

On the last evening of the show, the phone rang with the call I was anticipating.

“Dad! Dad! I won the grand champion jumper award with Blondie and the reserve champion with Squaw. I had so much fun. And those girls who made fun of me were coming up asking where I bought my horses. I think we should come back next year, don’t you?”

“I’m thinkin’ so,” I said, smiling. I couldn’t have been a prouder dad.

17.

Sorting the Seven Hundred

The

BLM

called and said a rep from Washington

DC

would be out in two weeks to view the horses. Twenty-five years of working with the

BLM

had taught me that field reps didn’t come from

DC

, bureaucrats did. I couldn’t get any additional information from the person who called. Maybe someone in the hierarchy had decided it was time to find out what was going on at Mustang Meadows and learn a thing or two that could be used to help unadoptable horses in other parts of the country. Then again, maybe that was wishful thinking. The

BLM

had shifted its policy this way and that over the years, spinning the weather vane in all sorts of directions. I wasn’t sure if the copper rooster would point north, south, east, or west. I guess I would find out when the rep showed up.

And show up she did, on the appointed day. I happened to be in the barn when I heard the crunch of gravel. I knew the Suburban was in the lot and John, Marty, and Russ out on horseback on the ranch. So it had to be her. A woman in jeans and boots, with a clipboard tucked under one arm, introduced herself.

“I’d like to take a look at your horses,” she said.

“Not a problem. We can hop in the Suburban here and go out to the meadow.”

I asked if she wanted a cup of coffee or lemonade first, but she declined, so we got down to business.

“You have a herd of fifteen hundred horses?” the rep asked.

“Yes, we’ve had that many for three years now.”

She didn’t ask the usual questions about the ranch. What’s it been like to care for fifteen hundred wild mustangs? Can you train them? Did you have to change the ranch to accommodate them? Nor did she comment on how calm they were when we drove through the herd. Her comments were more like, “Stop here for a moment,” and she would proceed to look in every direction and make notes on her clipboard. We spent a good two hours meandering the truck through the herd. She would point in the direction we should go. I’d see horses that I recognized. The big blue roan with only one eye and scars running down the left flank. The squatty chestnut mare, one of the smallest horses in the herd. And the palomino sisters. These were a few of the unadoptables that formed our family, and I couldn’t help but be proud of all that we had done together. As we went along, I daydreamed. A couple of times I got out and pulled on the grass. I made a mental note to tell John we’d best move the horses in three days.

I wasn’t paying attention when the rep said go to the left. I knew the ground there was soft because a spring ran nearby, and what did I do but drive right into the mud. I felt the truck sink. No way could I drive it out. I put my arms over the wheel and looked up at the bright sun above. Good thing it wasn’t raining.

“Well, it’s almost lunchtime,” I said. “How about a little hike back to work up our appetites?”

On the way back, we small talked about her career with the

BLM

and a bit about the ranch and this part of South Dakota. John, Russ, and Marty already had arrived in the kitchen when we got there. They hadn’t seen us walking in on foot. I told them about the Suburban getting stuck and said that I’d get a tractor out there after lunch and pull it out of the mud. We finished the sandwiches Debbie had set out before leaving to run errands in town.

“Anything else you’d like to see?” I asked the rep.

“No, I’ve seen all that I want to see. I do have a few more questions before I leave.” The boys took this as their cue to excuse themselves. She asked how difficult it was to handle the horses. Could we sort them easily? I explained we had them trained and yes, it was easy to bring them in and sort them. For a moment, I thought she might inquire as to how we had accomplished that feat.

Instead she said, “I want you to cut seven hundred horses. Cut the largest animals by weight and size. We’ll schedule drivers to pick them up. Can you do that within two weeks?” Her placid expression seemed to indicate that this request was quite ordinary.

But I had just been thrown on the ground in a wrestling maneuver and had the wind knocked right out of me. I stared at the sweating glass of lemonade in my hand, stunned. This is what the

BLM

had in mind when they called?

“You want me to cut seven hundred horses? That’s almost half our herd.” She nodded. “What’s the

BLM

going to do with them?”

“We’re putting them in the adoption program.”

The disbelief that flooded through me had to have registered somewhere on my face. Our horses had been deemed unadoptable. They were brought to us because no one wanted them. Many of our largest horses were scarred or crippled. They were not pretty horses. If they hadn’t been adopted the first time around, they weren’t going to be adopted the second time. Unless there was another reason. I took a sip of lemonade.

“So the

BLM

feels these seven hundred will be adopted?”

The woman sitting in the chair next to me nodded yes. Her expression remained steady.

“And it doesn’t matter if they limp or are missing an eye or have scars all over? You want the seven hundred largest animals regardless of physical abilities?”

“That’s correct.”

“Regardless of color? Health? Looks?”

“Yes.”

“You want the largest horses. The ones that weigh the most.”

She looked down at her clipboard as if to check it and nodded. Right then I saw through it. Their transparent plan. It wasn’t even cloaked in plausibility. Earlier in the year the price of horsemeat had taken a significant jump up to eighty cents per pound. If you adopted a horse, you couldn’t legally sell it for a year, but after those twelve months you could sell it to whomever you wanted. As far as I knew, no one policed sales to make certain they didn’t happen during that first year.

My mind scrounged for options. We had the first-ever government-sponsored wild horse sanctuary and were bestowed with the responsibility of caring for these horses. We had A ratings across the board. We had made improvements in the ranch to accommodate the horses and we were now operating a well-oiled machine. This didn’t seem to matter to the

BLM

. Some people somewhere saw dollar signs and were making decisions. In my opinion, which didn’t hold an ounce of water, they were the wrong decisions. The

BLM

owned the horses and could dictate what they wanted to do with them. I was landlocked here. I had nowhere to row.

“Circumstances sure must have changed for seven hundred unadoptable horses to now be adoptable,” I said. If I had had eighty cents in coins in my pocket, I would have laid it on the table. As it was, the number hung in thin air between us.

“Can you have them ready for us in two weeks?”

I shook my head yes.

The rep pushed back her chair and stood up.

Her last words before climbing into her car were, “I’ll have someone call you to schedule the pickups. I’m sure it will take some time to haul the horses out. I know the trailers only carry about thirty or forty horses.”

“Forty,” I said.

“Forty. That would be about twenty-six trailers.” She was quick with math. She probably had already figured out that a thousand-pound horse at eighty cents per pound would bring in $800. Some buyers would be willing to pay the

BLM

’s $150 fee for an unadoptable, wait a year, then sell their real estate to a slaughtering house for the $800. The

BLM

could get rid of horses, which they were always trying to do. The spirit of the law said horses couldn’t be slaughtered and technically the

BLM

was honoring that spirit. But the veil was sheer. This was slaughtering with a straw man in between.

I watched her drive away. She hadn’t been friendly or unfriendly. She was doing somebody’s bidding, but I didn’t know whose and suspected I never would. This was a huge shift in policy that would not receive any fanfare or public announcements. Perhaps if I were the muckraking type, I could dig around for a trail and go sniffing along it, then raise hell. But I preferred the smell of healthy green grass and the animals that fed on it. In my mind, the sanctuary was a permanent home for unfortunate horses. At the moment, though, it felt more like a pawn on the government’s chess table. I shifted my thoughts away from the game and onto the needs of the horses.

I climbed onto the tractor and swung it toward the stuck Suburban. For the first time, I was glad that Happy was no longer here.

That night I talked to John. We had a new issue to face. In less than a day, our thriving, profitable ranch had lost 50 percent of its income. What effect would this have on our future? We needed to do something to keep the ranch solvent and running. We had the water tanks, windmills, grass, corrals—so much had been improved on the ranch.

“Maybe I could lobby for more horses,” I said to John. He took a long drink of beer and shrugged his shoulders.

“I’m not sure you can count on the government to give you more. Seems like they’ve been taking away a lot more than they’ve been anteing up.” He looked as skeptical as I felt. It was hard to dredge up the energy to think of dealing with the

BLM

to get more horses. “What about running cattle?” he said.

I had thought about this. We had a ranch designed for horses, but we could make some changes to accommodate cattle. We could replace the seven hundred horses with about one thousand head of cattle. Did I want to do that? Not particularly. Did I need to do that? The bottom line voted “yes.”

It took us six hours to sort the seven hundred largest horses. Once that task was completed, we turned the remainder of the herd out in the pastures and kept the selected horses in the corrals until the

BLM

’s two contracted trucks arrived. We’d load the trucks then wait for their return. It took seventeen loads and one month to haul them all away. The horses went out to five separate adoption centers. I never heard whether or not they all got adopted and didn’t have the heart to ask.

I didn’t call the congressional representatives who had sponsored our bill. They might have spoken to the

BLM

and objected to the whole thing, but I retained a sense of optimism. Time and again we’d proven ourselves good caretakers of the horses. If the

BLM

now had a better plan for caring for horses, I had no objection. I was interested in the well being of the animals, not in the underlying politics. For some reason, the

BLM

didn’t take any of Dayton’s horses. I never found out why.

Since the horse herd was cut in half, our ranch was now under-stocked. I couldn’t get the

BLM

to talk to me about bringing us more unadoptable horses, so John and I started gearing up to bring in cattle. It’s more difficult to run a ranch operation with two different types of livestock. When all we had was horses, we could focus on them at all times. Cattle need as much, if not more, attention than horses.

The eight hundred remaining horses still looked stately out on the pasture and I still loved them, but I could feel a hole, a disconcerting emptiness. I needed a friend. Aunt Jemima. She would be the perfect companion right now. I drove down to Lazy B, loaded her in the trailer, and hauled her up to South Dakota. I’m not sure if it was a good thing or a bad thing for her, but for me, it had the flavor of a family homecoming. I put her in a stall next to Clyde.

Marty took one look at her and said, “All your Arizona horses so small?”

“She may be small,” I said, with a brush of irritation, “but she has a huge heart. Takes up half the space in her.”

The South Dakota horses were bigger in every way, including having hooves like paddles that could ride the sand like snowshoes. Jemima’s hooves, however, were made to traverse the rocky terrain of Lazy B. For her, traversing the prairie was like walking on a sandy beach. When she took a step, her hoof sank a good five inches. Pushing off the soft soil required different muscles and extra energy. Consequently, the other ranch horses could travel faster and farther. Although I couldn’t take Jemima out on long days, we did quite a little work together on easier days.

Shortly after Jemima arrived, I purchased four hundred head of cattle. One day the boys and I rounded up a group of cows and herded them into headquarters. I was riding Jemima and she was happy to be in her element. We had pushed the cows against the gate and they were just about to go through it into the corral when a little doggie calf bolted away from group. We knew this little guy. His mama had died when he was quite young, and he had survived by sneaking up on nursing cows and stealing their milk. Often a cow won’t pay much attention to a nursing calf, assuming it’s her own. In this fellow’s case, when the cow took notice of him, she kicked him away and wouldn’t share her milk. The calf was smaller than he should have been, but he was a feisty little survivor. Before we knew it, he had run over to the swamp on the other side of the corrals and jumped in. He splashed out in the muddy water happy as could be.

Aunt Jemima saw the doggie turn out from the bunch. She just wasn’t about to let that calf get away, so boy, she went right after him. She raced right up to the edge of the swamp and without a second of hesitation jumped in with me still in the saddle. Jemima swam toward the calf playing in the reeds on the far side. Her legs churned and she grunted. A big hump of grass stuck out of the water in front of her. Maybe Jemima thought she could get a foothold on it because she swam right up to it. Her momentum pushed her on top of the island and there she sat, high-centered and stuck, her circling legs unable to dig into the mud or propel her forward. I slid off and got wet clear up to my neck, but I was able to pull her off sideways and drag her to a place where she could get some traction. I was laughing and trying not to swallow water.

After all this commotion, the calf decided that he had had enough of us chasing him around so he splashed over to the swamp’s edge and scrambled out. Aunt Jemima followed him and slogged out, dripping water. The cowboys witnessed the entire event and had a few remarks when I rode up covered in mud. I got a kick out of Aunt Jemima showing her big heart. She wasn’t going to let that calf get away and would have followed him to hell and back. That was Jemima, though. She got the job done. That was our shared philosophy: you do what is required of you, even when you might not want to do it.