Horse Lover (14 page)

“Does he need to be in the hospital?” I asked.

“Dad, no. I’ll be fine. If we get going, we’ll be done by noon.”

“What do you think?” I asked Ralph.

“You can take the safe route and go to the hospital.” Ralph frowned in contemplation. “Or not.”

I could see where this was going. If I had done the face plant and could get up and walk, I would be saying the same thing as my son. What every family needs — two stupid, hardheaded cowboys. I looked at the horses now scattered around the pasture. The day had done a face plant. Maybe we didn’t know enough about these horses. They had been following us beautifully. What could have triggered those two ornery animals to charge? We’d never be able to answer that question.

The logical side of me said to call it a day, take my boy to the hospital, get him checked out, return to the ranch, and regroup. At the same time, a different voice yapped in my other ear. Stay. Finish the job. Al is banged up good, but he and his horse are okay. Trust me, like you have all the other times. I recognized that voice, the one that had said let Aunt Jemima chase the runaway steer, the one that said don’t give up on Blackberry, the one that had urged me to buy the ranch and lobby the government to support a wild horse sanctuary.

11.

Horses passing through a gate on their way to summer grazing

I looked at Alan. “You sure you’re up to this?”

“Let’s go.” He took the reins of his horse from Russ.

We had a board meeting right there. We decided that those two horses knew exactly what they were doing and should they or others reenact the attack, we’d take their advances seriously and get the hell out of the way. I didn’t understand how those horses had communicated to turn at the same instant. They had been in exact lockstep. Had they been out in the pasture practicing this move when we weren’t around?

The horses gathered easily. John and I moved out front again, leading the horses around the pasture, this time counterclockwise. I didn’t want to mimic what we had done before and the only variable that could be changed was direction. They hit an easy gallop. When we neared the west gate, John picked up the pace so he could open the gate into the Big Horse pasture. I felt pretty sure the lead horses would follow me through, but still my breath caught as I rode between the gateposts. The horses behind me threaded through like they’d done it a hundred times before.

We continued without incident across the three-mile pasture. Over a little hill lay the gate leading into the West Whitelands pasture, which was two and a half miles from Mud Lake. John opened the gate and the horses never slowed. On they went. Too fast, as it turned out. Clyde’s gait changed ever so slightly, indicating his gallop required more effort. I motioned for John to keep going and slowed down. I didn’t want Clyde to run down. I pulled to the side and trotted as the leaders galloped by. I thought of Saber — big, athletic, able to travel long distances. He would have been the perfect horse to ride on this venture. I pictured him gliding over the sandy country. I spent but a moment with him, then tucked him away. I was needed here and now.

I looked back. A chestnut mare had turned and for a second I thought she was going to bolt from the herd, but she ran to check on her foal. Ah, it was the mama of the gangly-legged, youngest baby that was having a hard time keeping up with the herd. Mama pushed him from behind. He put his head down and tried to run a little faster but couldn’t quite get there. Mama ran ahead of him searching for help. Not finding any she returned to her baby. Ralph noticed the colt and decided to help by honking the horn. The harsh blares blew above the soft thunder of hooves. Despite his best intentions, his honking was spooking the horses. The leaders picked up the pace. The edge of pandemonium started to encroach. Russ was riding closest to the colt. I broke from my position and rode back to him.

I pointed to the colt. “Go catch him,” I yelled to Russ. “He’s not going to make it. Use your saddle rope to tie him in the back of the Suburban.” Russ nodded and veered toward the struggling baby. I pointed Clyde west again toward Mud Lake. Al Jr. rode ahead of me and didn’t appear to be under any stress. We still had at least a half mile to go.

Clyde slowed some more. With John, Marty, Alan Jr., and Jordan up front and handling everything well, I fell back, letting Clyde choose a comfortable gait. The Suburban grumbled behind me. I looked back to see where it was and almost fell out of my saddle. Ralph, still in the driver’s seat, had acquired a most unusual passenger. Russ must not have tied the colt down, and somehow the little guy had climbed from the back of the truck to the front and plopped in the front passenger seat. He looked like a Great Dane with both legs on the dash and licking the windshield. In front of the vehicle, his mother raced back and forth, frantic to get her baby back. The baby stopped licking and parted his teeth. He probably nickered for his mama, and she sure as heck heard it. She turned toward the Suburban, flattened her ears, and charged. Ralph watched in horror. He couldn’t back up or turn, so he stopped. Just before she ran into the hood, she spun around in a cloud of dust and kicked out the front grille. Ralphs’s mouth dropped open as she vented her fury on the metal. The colt looked like a little kid cheering his parent. My mouth dropped open, too, a belly laugh bursting out at the sight of the big colt next to the ace bomber pilot who sat there wide-eyed. Oh, for a camera. Frustrated, Mama ran off to catch up to the rest of the herd. Nothing could be done about her tantrum right now. We’d resolve the issue at Mud Lake.

By this time, the lead horses were half a mile ahead and had started to flow through the gate into Mud Lake pasture. John, still on horseback, stood beyond the gate and off to the side watching. With no lead man to follow, the herd fanned out. The other men’s horses began to fade. The pace we had kept was too fast for the saddle horses to maintain. No one had anticipated this happening.

Clyde and I were the last horse and cowboy to ride through. The Suburban followed with the colt still in the passenger seat and Mama running back and forth next to the moving vehicle. Ralph pulled to a stop. I dismounted and walked over to the truck. When I opened the door, the colt twisted and turned until one skinny foreleg flopped out, then out popped a head with searching eyes. Since his mother was practically breathing down my neck, I helped the little guy out. He stumbled for a few steps, but Mama propped him up with nuzzles and offered a good long drink of milk. The look she gave Ralph clearly indicated she didn’t want him as a babysitter ever again.

12.

A colt trying to keep up with his mama

13.

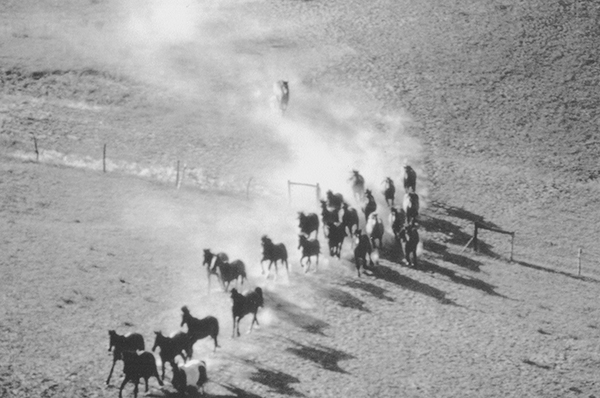

Horses galloping across the prairie

The horses seemed pleased to find an abundance of tender, sweet grass. Happy stood at the outskirts of the herd, his neck curved toward the ground. The palomino twins grazed near the middle, the family of roans nearby. I recognized other individual horses here and there. All had made the journey successfully. The breeze blowing against my back delivered a sense of accomplishment. It eased through me, softening the disappointment that I had been feeling over the wreck and our horses tiring. I had never imagined either of these things happening. I reminded myself that everyone arrived here in one piece and the horses had followed the leader for six miles. I joined the cowboys unsaddling in the old corral.

“Load up, boys, the bus is here,” Ralph said. Seven magnificent cowboys, one emptying the sand out of his boots, piled in. We all had a story to tell. Over ham and cheese sandwiches in the Pitkins’ kitchen, I related Ralph’s little adventure, which set everyone to laughing so hard they could barely eat. It was destined to become part of ranch lore. There was a consensus that in the future motorcycles would come in handy for long treks. No one said, or even insinuated, the wreck had tarnished our once-in-a-lifetime day.

That night I crawled into bed exhausted and fell asleep to the sound of hooves pounding the sandy soil and a vision of tails and manes waving free and easy in the wind.

13.

Saber

The new colt in the corral at Lazy B headquarters caught my eye. The cowboys had brought him, his mama, and the eight other mares and ten-month-old foals in from the pasture where they had been born. It was weaning day. It took an hour to separate mamas and babies. The mares took a last, long, loving look at their foals and with a goodbye nuzzle headed back on their own volition to the pasture for grazing. Since they were only a few months away from the birth of their next babies, their bodies were telling them it was time to wean the current foals. The colts didn’t have a chance to mourn their departed mothers; they had to start school. The curriculum included learning to lead, learning to load in a trailer on command, and learning to trust the two-legged creatures who were now picking their feet up and asking them to stand still. We rewarded them with the new taste of grain.

This particular colt had a larger build than his peers, with a broad chest, smooth barrel, and muscular hips. The dark hair that most foals have at birth had been replaced with a shiny white coat, a dark stocking above each hoof, a black mane, and a streak of black down his backbone reminiscent of Spanish influence. He explored his new territory, poking along the fence, his nose up and ears forward, and when the cowboys weren’t holding class, nudged his more timid companions into games. He was the leader on the playground, and he brought home a report card full of As, though sometimes the teacher had to work at keeping his attention, which drifted if he learned the lesson quickly and became bored.

I felt an instant attraction similar to what you feel when you meet someone you want to get to know better. Maybe it’s the energy in the smile and eyes or the sweep of hands in conversation, or you see a glimmer of something that reminds you of yourself and you know that you want to start spending more time with that person. This little white guy fit those characteristics. I could see him in my string of horses. It wasn’t a decision I needed to make right then since he was headed out to Robb’s Well for the next fifteen months or so.

When I was in the area of Robb’s Well, I would stop to see the young horses. I observed how they walked and how much they had grown. I also did a sort of mental check-in to see if it was time to integrate them into the ranch system. Which horses in our strings would soon be retired? How many hands were available to bring them in and break them? When we had the extra hands I’d send out a few cowboys to round up the horses at Robb’s Well, cut five or six of the biggest ones, and bring them into headquarters for breaking.

I had been keeping an eye on the white horse. The day he arrived at the corral, I was waiting for him. Though he had not yet attained full stature, the muscles in his upper legs, forelegs, and haunches had thickened, and the vertical between his belly and the ground had lengthened. He had a smooth, effortless gait that exuded confidence. Based on his physique, coordination, and disposition, I already could tell the white horse had the potential to be an athlete. I could see the disappointment on the cowboys’ faces when I said, “I’ll take that white one for my string.”

He needed a better name than “that white horse.” The best way to name a horse is to allow the name to emerge. It always does. Once, as teenager, I named a horse Dumas. My dad and I attended the 1956 Olympic trials at the Los Angeles Coliseum, and we saw Charles Dumas set the world record by clearing seven feet in the high jump. Shortly after, one of our young horses went and jumped a six-foot-high corral and I promptly named him Dumas. Aunt Jemima found her name when a can of syrup stuck to her foot. And her mother, Tequila, well, we don’t need to go there.

The white horse reminded me of Robert E. Lee’s famed white horse Traveller. I recalled seeing some photos of Lee mounted on this steed, dressed in full military regalia with a saber hanging at his side. Saber. Now there was a strong, steadfast word. “Hey you rascal,” I said to him one morning, my arm extended over the fence into his space. He trotted over for a pet. “You good with the name Saber? I’m thinking you can live up to it. What do you think?” He pushed his nose against my shoulder.

Saber and I began to get acquainted. Since he wasn’t full-grown, and probably wouldn’t be for another year, he couldn’t do a hard day’s work, but he could join me on less demanding days. Saber had an idea of what he wanted, and what he wanted didn’t always agree with my bidding. Sometimes he could get a little prickly. He never bucked, but he didn’t always want to cooperate. If I wanted him to turn right, he pulled to go left. If I rode him with spurs and touched him, and I rarely touched him, he’d look back and kick a hind foot at the spurs or try to bite them, an especially annoying habit. By this point in my life, I had moved away from the Jim Brister style of breaking a horse by breaking his will. Too often this required punishing a horse severely and I had grown unwilling to settle for the consequences. Candy had drowned and Sally’s entire personality changed. I had vowed to break Saber in a more gentle fashion. Except this required dredging for patience because Saber could be like a burr in my boot.

One day we were driving cattle back from New Well to the Lazy B headquarters, a six-mile trip. The previous two days of rounding up had been difficult, dusty work, but this was an easy day so I opted to ride Saber. Jim Brister was pointing the cattle up front with another cowboy. The herd fanned out behind them. I brought up the drag in the back with the rest of the cowboys to show that I wasn’t above doing drudgery work. I could see the whole show from there and could tell who was or wasn’t carrying his load. Maybe Saber wanted to be in the lead or maybe he was bored. Whatever the issue, he was crankier than a teenager awakened from a sound sleep. I’d spur him along and he’d turn and try to bite me. It seemed like every hundred feet I was pulling his head up and scolding him. I was getting annoyed at him being annoyed at me. That’s when I saw Jim break from the lead and circle back toward me, something he wouldn’t do unless he had to unload a piece of his mind.

He rode up next to me and gave Saber the once-over. “Alan, if I were on that damn horse, I’d draw that knot in your get-down rope and whip that thing against his sheath until he squealed for mercy.” I held back a wince. The sheath protects a horse’s penis and is a very sensitive area.

Saber’s strong shoulders shifted rhythmically under my saddle and a cow in front of us called out for her calf. I didn’t want to argue with Jim or go against his judgment. I may have been the boss, but Jim was my senior and my mentor. For the first time in my life, I bucked his opinion. “Well, I’m trying something a little different on him this time. I’m going to give him a chance to learn it on his own,” I said.

Saber turned his head and jabbed his mouth at my spurs. Large teeth flashed between curled lips. I yanked the reins, pulling his head back. Jim looked straight ahead and without a word rode off.

“Damn it, Saber. Knock it off. What are you thinking?”

Saber jogged a few side steps. I took a deep breath. It was going to be a long day.

Not every day with Saber was long, and of course I didn’t ride him every day. Occasionally he would be so interested in the task at hand that neither of us remembered that I wore spurs. Within a few hours, however, he would bicker with me, forcing me to ladle out more patience and reaffirm my vow of training. I could see his potential when I watched him in the corral, feel it when we galloped, trotted, or even walked. He was long-legged, powerfully so, and could outrun his peers. I never timed him or any horse, but if I had I suspect he would have won the race by many lengths. I babied him with extra grain, and like a teenage boy inhaling any food put in front of him, he continued to grow.

As he learned cowboying, I learned gentle horse training. Most cowboys forced a horse right there and then to submit to their will. Within a day or two, the horse wouldn’t have an ounce of argument left. More often than not, when Saber returned to the horse pasture for the night and I slid off my boots and hung my hat, issues between us remained unresolved.

About three months after Jim offered his advice, something happened. It was an unassuming day. Saber and I led a crew of cowboys to cut out cattle for sale. The sun spilled over us, bright as always, and a mischievous breeze scrambled the desert dust with the thuds of hard hooves and the sweat of men on horseback. We were nearing a late lunch when it hit me. On any other day, Saber would have tested me a dozen times by now. But here he was with his head and ears held high, so fully engaged in his job that I hadn’t needed to reprimand or spur him once all morning. In fact, he had just moved a large steer to the outside of the herd with little direction from me. I had eyed the steer and thought, okay, this guy needs to go. Maybe my hands had slightly, perhaps subconsciously, pulled the reins in the steer’s direction, but maybe not. Maybe Saber read my mind. Regardless, he had moved the animal, slowly, gently, and before I knew it, had the steer in exactly the right spot at the edge of the herd. A new alertness tensed his body. I could feel us working together.

I said, “Wow, Saber, you’ve arrived.” It was like what a hunter experiences the first time his young dog points, waits for the shot, then perfectly retrieves the bird. By the time we returned to headquarters, I was sitting on a completely different horse. For whatever reason, Saber’s resistance had hopped off the train and full cooperation had moved in. From that day on, Saber became the best cow horse I ever rode. When we were out on the range, he seemed to know what I wanted to do. It was as if this athletic, smart companion could read my mind. I’d throw the saddle over him, chitchatting about the day like you would chat to your best friend, and then we would have the luxury of spending the entire day together, hanging out, running into challenges, having adventures. The line between work and pleasure dissolved.

About the same time, Saber did another extraordinary thing I’ve never seen a horse repeat. One morning, the air cool against our faces, we set out at Saber’s usual gait. I urged him to walk a little faster. I felt his gait change. He had broken into a running walk, the same gait as a Tennessee walking horse. No other horse on the ranch had such a gait, so he hadn’t learned by imitating. His body naturally slipped into the pattern. I didn’t even know how to respond except to enjoy the ride. It was like stepping off a tractor and into a Lexus.

“What the hell got into your horse? He just hit fourth gear. How’d you teach him that?” said Cole, pulling up beside me. His horse had to hit a long trot to keep up with Saber.

I shrugged my shoulders. “Good cowboys get the best out of their horses,” I said. Three miles later Saber wasn’t even out of breath. The boss always sets the pace when riding out to the roundup and cowboy culture says you never gripe about that pace. But that day the crew certainly looked disgruntled.

Another time, on an early fall day, the cattle were scattered on the High Lonesome pasture in the Summit section of Lazy B, a half-day horse ride from headquarters. I gathered a crew of cowboys and, to save time, we loaded our horses in trailers and drove out to Summit. Saber was still young, a green colt that could handle a day of rounding up cattle spread out over the six square miles of pasture.

The grass at High Lonesome grew the thickest on the ranch. It didn’t have to angle around mesquite trees or contort between rocks. It just had to poke its head straight through the soft ground and drink the sunshine. Only an occasional badger hole dotted the ground.

I assigned each cowboy an area of pasture. We had just started to spread out when a coyote jumped up right in front of Saber and me. Its gray, mangy body tripped my cowboy switch and I plunged right into roping mode. Cowboys are trained practically at birth to go after anything running away from them—rabbits, bobcats, calves, coyotes. It’s not that you need to catch the animal. It’s the challenge of the event. Are you good enough to rope the critter? If you do, you’ve earned your bragging rights.

I turned Saber on that coyote. He knew exactly what we were up to and caught up to the coyote like he was standing still. I jerked my rope down and built a loop. I leaned forward to throw the loop, and

BAM

, Saber stepped in a badger hole. His front end jolted down. His back end popped up. We were going so fast I didn’t have a split second to lean back and regain my balance. The sudden stop shot me over Saber’s neck, ass over teakettle into the air right toward that running coyote. The only thing going through my harebrained mind was, oh shit, this really is going to hurt. And it did.

I rolled to a crumpled stop and lifted my head, looking for Saber to see if he had broken a leg. He was getting up from his fall, twenty feet away, and had a terrified look in his eyes. He didn’t even shake himself but took off running, a white streak across the brown desert. Aw hell, is about all I could think. Well, at least he ran without a limp. I pulled myself up, my rope still in hand, and hobbled across the hard ground after my hat, cussing myself out for being such a stupid cowboy to rise to this bait. I surveyed my distant crew. You would think by the way their horses’ rear ends faced me they hadn’t seen my dumbass attack. But I knew they had. Feeling the fool, I began limping along the two-and-a-half-mile trek across the pasture to reclaim my horse. He wouldn’t be able to go beyond the fence, but would he be able to forgive me? If I hadn’t been on Saber, I never would have tried to rope that coyote. No other horse could have caught him.

An hour later, a few cowboys started heading toward me, Saber in tow.

“Gee, boss, what happened?” Snicker.

“You know what happened. Don’t you be laughing at me. You all have had a fall before.”

I took the reins. “Saber, can you forgive my stupidity? I shouldn’t have turned you to that coyote. I’ll try to be a better friend to you from here on. I owe you one.” I climbed back in the saddle. And Saber? Friend that he was, he went on like nothing had happened.

By the time Saber was five, he was so powerful and fast that when we worked cattle I always held him back a little. One day, curiosity got the better of me. I finished lunch before anyone else at the bunkhouse and didn’t feel like shooting the breeze, so I headed outside to get a jump on re-saddling Saber. He was feeding with the other horses in the corral by the barn. That morning we had herded four hundred cows and another two hundred calves into the large working lot at headquarters, where we would spend the afternoon selecting and cutting cow-and-calf pairs. Calves over six months would be sold; younger calves would be branded and remain on the ranch.