Horse Lover (10 page)

I should have named her Pegasus, because Candy just about sprouted wings. She leapt into the air and plunged in the middle of the water. I slid off the saddle still holding the reins, prepared to do what cowboys do when you swim with a horse. With one hand, you hold either the saddle horn or the tail and let the horse pull you around. Kind of a western version of swimming with a dolphin, though I wouldn’t exactly call twenty pound chaps and a pair of pointed leather boots a version of a wetsuit.

I didn’t get a chance to grab the saddle horn or Candy’s tail. Her back end sank under water and she started flailing her front legs and thrashing her head. She couldn’t swim! I had never seen a horse that couldn’t swim. I tightened my grip on the reins and tried to keep her head above water. One leg came down on my head and knocked me underwater. I kicked back up. A hoof hit my shoulder hard, another glanced my ear. I dodged another hit, still trying to hold her head up. Water was getting in her nose and she was snorting and rolling her body back and forth and trying to climb all over me. I went under again, this time with a mouthful of water. I came up gasping for air. The water roiled around us. Candy pawed harder, desperate to find solid ground. She was starting to push me around and under. I couldn’t hold her up anymore. I could barely hold myself up. I let go of the reins.

By the time my boots hit soggy bottom, the muddy water had swallowed Candy. No burping bubbles marred its dark surface. I crawled up on dry land, my chest heaving with exhaustion. What felt like a twenty-minute struggle surely had been no more than five minutes. Hell, maybe three minutes. I was numb to the bruises I sustained, numb to the glory that had been in the day. Disaster had struck with the fury of a cyclone, a tidal wave, a horse that couldn’t swim. How could a horse not swim? They were like dogs. Every dog can swim. Candy had tried to tell me she couldn’t swim, but in my frustration and need to win the battle, I had failed to listen. I was not numb to the feel of being a fool and to having my heart broken by my own stubbornness.

I sloshed back the mile and half to headquarters in a flabbergasted fog. I could still see our trail through the grass. I had been out for a ride on a young, healthy, pretty horse and now she was dead. I stumbled my way over uneven ground, wet chaps swishing, boots sloshing, talking out loud trying to figure out the whole situation. If I had named her Squaw Piss would she have died? Probably. But I couldn’t say for sure. All I knew was that I failed her. And here I was doing the cowboy walk of shame back to the ranch, my horse on the bottom of a stinking water hole. I was an idiot. I lost a horse and a friend. What kind of cowboy was I?

That day I was a jumble of recriminations—guilt, anger, regret. I was not in a place to learn. But in the following weeks and months, I looked hard at my role in Candy’s death and acknowledged I had failed my horse by not paying attention. I vowed from that point on to be receptive to what my horses were telling me.

9.

In Training

The day after the horses played ring-around-the-rosy with us in the horse pasture, I started the training. Monty Roberts and his horse-whispering manual had not yet appeared on the scene, and in my research and meanderings I never had bumped against anyone who trained a herd of wild horses. Training one adopted wild horse, maybe even two at a time, was business as usual. But training a group of a hundred, then another group and another, up to fifteen groups, up to fifteen hundred horses? Then merging them into one herd and getting that herd to follow men on horseback with no renegades blasting out? Even for a lifelong cowboy that was one heck of a wow. Yet I held to the belief that herd modification training would work with horses just as it had with cattle.

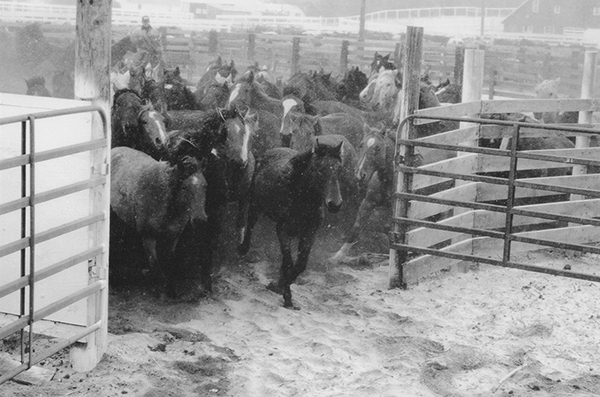

The four hundred head remained in the same corral where we penned them the day before. With another dose of difficulty, Russ, Marty, John, and I cut one hundred horses and drove them into the training arena. They gathered at the far end, a nervous bunch shaking their heads, shifting around as if threatened by shadows dancing on the ground. I gathered the cowboys at the opposite end. Anticipation filled our corner. I didn’t want anyone to go out swinging like a hyped-up boxer, so I laid out a plan.

“Let’s spread out and take it at a walk. No quick movements. Just ride toward the group.” The three men, all professional horse handlers, nodded. “And at the same time, we’re going to talk to them. Out loud. Real friendly.” No one said a word. “You know,” I said, “talk like you’re sitting across from your buddy having a beer at the end of the day.” Russ shifted slightly in his saddle and looked down. It’s bad cowboy etiquette to roll your eyes at the boss. John looked thoughtful for a moment, then jogged his head as if the concept clicked. We were out to make friends, win the horses’ trust. No yelling. No getting frustrated or angry. We headed out toward the jittery group.

“Easy does it. We’re not going to hurt you.”

“No need to get that wild look in your eyes.”

“We’re all friends here.”

We had walked halfway down the corral, chatting steadily, when a bay mare at the edge of the bunch decided she’d had enough. She sprang into a run, headed for the opposite end of the arena, setting an example for the other ninety-nine mustangs. I pulled up on Clyde as horse after horse whizzed past, so close I could have reached out and touched them. The whites and darks of their eyes blurred into orbs of fright and suspicion. As abruptly as it started, the stampede stopped. The horses stood, for a moment more confused than afraid. Their run had been cut short by corral fencing. I turned the crew around.

“All right, here we come again. Let us get a few feet closer.”

“Bay mare, why don’t you stay in the bunch this time? It’s a safe place to be.”

“Steady, there. No need to bump each other.”

“You horses, you’re doin’ great . . . uh oh, there you all go again.”

It was a reenactment of Palomino Valley. Horses crowd in corner. Cowboys approach. Horses bolt to other corner. It would take time before these animals figured out our intentions. Fortunately the dimensions of the arena would give them no choice but to pay attention to us and listen to what we had to say. The memory of Roy’s niggling voice tried to rebuke me for thinking wild horses could be trained. I muffled his words.

After twenty minutes of this back and forth, the mustangs started showing frustration and looked harassed. “Let’s give ’em a break, guys,” I said. We returned to the barn to unsaddle.

“Boy, they don’t like to catch you looking at them,” said John, dismounting. “More so than any horse I’ve ever trained.”

“I’m not so sure those critters are ever going to be our friends,” said Marty.

I settled my saddle on one of the cedar racks. “Well, we were able to get a few feet closer before they got ouchie.” I poured some grain into Clyde’s manger. I could see what lay at the heart of the training program—a massive amount of repetition and patience. We were about to become kindergarten teachers teaching a group of horses to follow the leader and not stray from the group. Teaching a horse like Aunt Jemima or Saber was high school level compared to this. Unlike cows, horses dribble out their trust. We needed to collect it with the patience of an Arizona rancher collecting rain in a gauge.

“I’ll see you all back here in two hours,” I said, rubbing on Clyde’s neck. “We’ll get in there and do it again.” Russ looked perplexed. “It’s all about the repetition, boys,” I said. “Building trust through repetition. We’ll keep getting in there every few hours until they wake up and realize we’re not the enemy. That’s the only way we’re going to break them out of the races. Then, when they learn to follow us, we’ll start taking them through gates and corrals, then into the lane, and finally push them into the pasture.” I coated the words with confidence. “And remember this conversation because in four or five more days you’ll see a whole different set of horses.”

Of course, I had no idea how long it would take for the horses to change their behavior. One week? Ten days? Twenty days? We’d find out soon enough.

Two hours later, we returned to the barn, curried and saddled our horses. Over four hundred horse hooves again pounded the sand in the arena. Yet this time, we could get closer to them before they bolted. This was progress in my eyes, though nobody else commented on it. We again called it quits after twenty minutes.

At the start of round three, the horses were noticeably calmer. But my favorite bay mare bolted out of the group. I turned Clyde and charged after her. We ran her into a corner. “Get back in the bunch, you renegade bitch,” I hollered, ten feet behind her. That shook her up. She wheeled around and hightailed it back into the bunch as fast as she had left it. Come spring, when we needed to move the entire herd six miles to fresh pasture, we didn’t want any runaways. Lessons needed to be learned in the corral now, before the field trips started. Teaching feisty individuals that their comfort level was highest in a group and not on solo jaunts became an important part of the training.

“We can get one more session in before dark.” I hung the bridle on a nail. “See you here in another two hours.”

Before walking out of earshot, I heard Russ say, “Does he really think he’s gonna train these broomtails?”

“Hell, he trained two thousand head of cattle. Nobody would believe that’s possible,” John said.

“Shit, man,” said Russ. “This could take forever.”

Marty replied, “As long as we can do it horseback.”

I watched a broad-shouldered black-and-white paint flare his nostrils and puff out a soft snort. Some of the horses nearby cocked their ears back and echoed his recognition at seeing four familiar men on horseback enter the training arena. The mustangs’ sentiment and behavior had shifted during the five days of training. They had graduated to following one of us in orderly fashion around the corral. The herd had begun to accept us as the alpha males. Even the bay mare that spooked and kept breaking away realized she couldn’t go anywhere and no one was out to hurt her. The cowboys had accepted that this training would be their way of life for a while. No one griped. It was becoming as much a part of the job as feeding cattle every day. We just did it.

Clyde and I walked at an oblique angle toward the paint. “Hey there,” I said, “did you get enough breakfast? There’s plenty to go around this camp.” I avoided direct eye contact. He flipped one ear forward and one ear back, then nodded his head and began a chewing motion with his lips even though his mouth was empty. What was he telling me? It almost looked like he had a grin on his face. “You keep talking to me and I’ll figure out what you’re saying. And I’ll keep talking to you. It’s not like we come from different planets. Right now, though, I’m thinking you’re the smarter of us two.”

Clyde and I walked past the happy guy and wove through a group of roans that insisted on hanging out together. If they got split up while running around the corral, they quickly found their way back together. Their coats, with the characteristic fine dusting of white, had started to turn darker, heralding the onset of winter. A few grunted at being interrupted from grazing on the hay. They took one or two steps to get out of my way. Being with the mustangs never jangled Clyde. He refused to let their glares and snorts antagonize him, and when they reared up or raced past, he stood his ground like a big brother inured to the antics of wilder siblings.

John threaded his way toward us. “Couldn’t do this a couple of days ago, could we?” he said and grinned.

“They were wound way too tight,” I said. A mare with the markings of a Pryor looked up from eating and turned to face us. She chewed her lips like the paint had done and pawed the ground with a front hoof. “Glad to see you’re so interested,” I said to her. Were she and the paint saying the same thing?

“I’ve noticed a couple other horses do that,” John said. “Could this be their secret code of acceptance?”

By golly, of course. It made total sense. “You might have just hit the mother lode of this training system,” I said, feeling a trill of excitement. “Cows acknowledged us by getting more gentle, but it’s looking like these horses are giving us a high-five in their own language.”

6.

A wild mustang

The horses seemed to be recognizing that we weren’t like other men, who chased them with machines, trapped them in corrals, and did nothing to diminish their fear. Our training methods had opened the door to their world, and now they were saying hey, let’s be friends. And on day four of the training. If only Red and Roy could see this.

It was time to move on to the next lesson: “Going through the Gate.” Although the horses had passed through the gate to enter the training arena and had passed through numerous other gates, they remained timid about going through a new gate. I didn’t know what invisible wire they saw or maybe felt when they ran through that open space. Since moving from pasture to pasture required going through gates, it was imperative they get over their fear. I gathered the crew.

“Russ, you start leading the horses around the corral. I’ll open the gate and by the second pass, three of us will be ready to wing them through.”

Russ rode around. The horses looked up. A rangy sorrel that often positioned herself in the front next to the bay mare started following him. The rest of the group fell into line. John, Marty, and I headed to the gate in the corner leading into another corral.

Russ and his horse trotted toward us towing the pack, and he went through the gate. The sorrel came up to it and stopped almost in midstride. It was like one of those cartoons where everyone starts bumping into each other. Within seconds it became a cluster of horses. Heads pushed up against rumps. There was a chorus of nervous neighs. The lead horses just stood and looked at the gate.

“Bring ’em around again,” I yelled. John and Marty abandoned positions. Marty started out, got some of the horses to follow, and the pack loosened up.

“Guess they don’t like the gate,” said Russ, coming back through it.

I didn’t have to think long about this melodrama. I knew exactly what to do. If you can’t tell them, show them.

“Russ, as Marty comes around the corner, you jump in the lead with him and both of you go through the gate. Don’t even pause. John and I will push on the back. Show these horses that’s it’s not a problem to go through. They’ll see it’s safe and they’ll jump across.” Russ looked at me like my brain cells had fallen into my boots. Ah well, he didn’t have to believe me. I knew a horse could learn by watching.

When Russ swung in with Marty and went through the gate, John and I pushed hard on the back of the pack. The leaders paused for a second, then jumped over the barrier only they saw. The rest of the pack crowded through as fast as they could go, pushing and shoving, knocking the outside horses into the posts on either side. Eventually they were all through. I got off Clyde and shut the gate, happy to have crossed this barrier. I sent a silent thank you to Blondie, the horse that years back taught me her kind can learn by watching.

7.

Horses pushing through a corral gate