How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (15 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

“He very well might, Your Majesty,” I replied. “Thank you for your courtesy, and for your protection of Christmas.”

That night, after we'd finished our dinner of fish and Leonardo had retired to his laboratory with the beets, I told Arthur about my meeting with Charles.

“He loves Christmas too,” I said. “If only he can be strong enough to withstand the Puritans' demands to ban the holiday.”

“I'm afraid the Puritans squabbling about Christmas may prove the least of his worries,” Arthur replied. “The king is truly at odds with Parliament. He believes they must obey all his commands, and they believe he must be guided by their collective wisdom. At some point they will either compromise or fight. Another civil war in England is a very real possibility, Layla.”

Charles's disagreements with his Parliament continued. Parliament met at the king's command, and three times in the next three years Charles summoned it to meet, then angrily dismissed it when its members refused to give him the tax money he wanted and tried to keep him from appointing the royal ministers he preferred. There was much grumbling about this, not only in the London streets but throughout England. Though its members were all country lords, prominent ministers, or well-off merchants rather than real representatives of the poor working class, Parliament was still considered the one opportunity for the king's subjects to have some influence on his decisions.

Charles

Meanwhile, in my own small way, I tried to encourage Charles's support of Christmas. Occasionally, I took some ordinary white peppermints to the palace. I never actually asked to see the king or queen, but just left the package with a servant there. And, though it was not easy making my stealthy way into the royal palace on the night of every December 24 for almost the next two decades, each year England's Queen Henrietta awoke on Christmas Day to find a small package of special peppermints beside her pillow. It was especially lovely candy, from the batches Leonardo was able to successfully decorate with bright red stripes. I was careful, in delivering my occasional packages during non-holiday times, to leave only plain white treats so no one would guess the identity of the Christmas gift-giver. As it turned out, the queen, who had little belief in the Pere Noel of her native France or England's Father Christmas, decided the striped candy was a thoughtful present from her husband. She began to feel happier with Charles, and soon their marriage blossomed into a real love affair.

But the king's relationship with Parliament remained anything but loving, and several events during the next few years moved England ever closer to civil war. In the process, Christmas was in even greater danger.

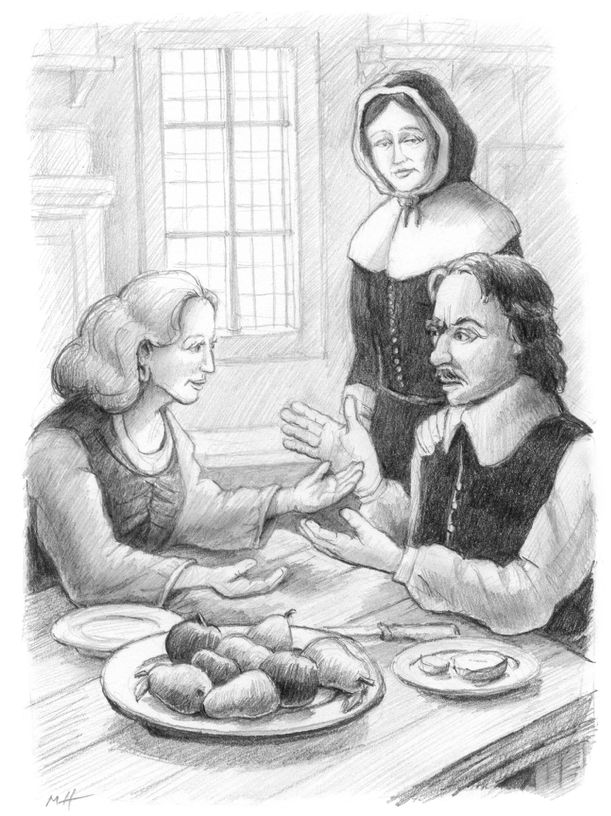

“Do you celebrate Christmas, Missus Nicholas?” Elizabeth Cromwell gently laid her hand on her husband's arm. “Our guest is here to talk about America, not to debate the merits of Christmas with you.”

CHAPTER

Eight

Eight

Â

Â

Â

Â

I

met Oliver Cromwell nine years after encountering King Charles in the marketplace. Unlike my accidental meeting with the king, my first contact with Cromwell came by appointmentâactually, by request.

met Oliver Cromwell nine years after encountering King Charles in the marketplace. Unlike my accidental meeting with the king, my first contact with Cromwell came by appointmentâactually, by request.

In 1634, religious and political problems in England remained unresolved. The Puritans were more outspoken than ever against all forms of worship other than their own. Charles infuriated them in 1633 by appointing William Laud to be archbishop of Canterbury. Laud supported what Puritans considered “liberal” church services with music and altar decorations. One of the Puritans, William Prynne, responded by writing a book titled

Histromastrix, or the Player's Scourge,

which attacked as sinful all forms of public entertainment from plays to sports, and particularly argued that Christmas encouraged bad behavior, not worship of Jesus. Few people could read at the time, and if the king had been sensible he would simply have ignored the book. But instead Prynne was arrested, and as a punishment for writing what he truly believed, he had part of his ears cut off. This unfortunately proved that Charles could be as harsh as his critics. “Half-Eared” Prynne became a symbol to the Puritans that they were in terrible danger for openly advocating their religious beliefs, and, frankly, it was hard to blame them, even though I disagreed with them completely about Christmas.

Histromastrix, or the Player's Scourge,

which attacked as sinful all forms of public entertainment from plays to sports, and particularly argued that Christmas encouraged bad behavior, not worship of Jesus. Few people could read at the time, and if the king had been sensible he would simply have ignored the book. But instead Prynne was arrested, and as a punishment for writing what he truly believed, he had part of his ears cut off. This unfortunately proved that Charles could be as harsh as his critics. “Half-Eared” Prynne became a symbol to the Puritans that they were in terrible danger for openly advocating their religious beliefs, and, frankly, it was hard to blame them, even though I disagreed with them completely about Christmas.

Puritans comprised only part of the king's political opposition. Almost everyone in Parliament was against him. Three times in three years Charles called Parliament to meet, and each time demanded money to fight wars. All three times, Parliament refused to immediately do what he wanted, and all three times Charles told its members to go home, instead of thoughtfully discussing with them how both sides could work together instead of remaining angry and adversarial. Then the king got his money by forcing rich people to make loans to him and by imposing new taxes on some businesses. This was clearly against English law; Parliament had to agree with any form of taxation. Charles said the law was wrong; kings had the God-given right to do as they pleased. Parliament was supposed to help him, not tell him what he could or couldn't do.

The members of Parliament responded by writing what became known as the Petition of Right, which stated that whoever held the English throne could not tax anyone or anything without Parliament's approvalâand, further, that no one could be arrested and punished without proof of a crime and that the king could not impose martial law on the country in peacetime, something Charles was always threatening to do. The Petition of Right was delivered to Charles in June 1628, when he either had to get the money to keep fighting his wars in Spain and France or else bring all his troops back to England. So Charles signed it, and in return Parliament gave him some of the money he wanted, but neither side was really happy. Charles believed Parliament had assumed too much power. After signing the petition the king just ignored it, levying taxes and arresting people as he pleased. Then, in March 1629, Charles went further. He announced that, for the time being, Parliament would no longer exist. He would govern without it. And, for the next eleven years, he did, despite continued criticism. If members of Parliament hoped English working people would rise up and demand that their representatives again be involved in government, they were disappointed. People in the so-called “lower classes” had enough to do keeping their families clothed and fed.

So in 1634, the king's political and religious opponents were feeling especially frustrated. There was no swelling of popular support for their causes. This is why some of them, including a rather obscure man named Oliver Cromwell, were ready to give up. Now, in a few more years everyone in England would know Cromwell's name, but at that time he was just another outspoken Puritan.

I certainly had never heard of him until one afternoon in the spring of 1634, when one of the women who worked in Arthur's toy factory hesitantly approached me. Arthur employed several dozen people, who would come to the factory in the morning, work during the day, and then go home to their families. He paid a wage that was more generous than most salaries of the day, but not so high as to attract undue attention. None of these people acquired our special powers of not aging and the ability to work and travel much faster than normal folk. We were careful that they wouldn't work at our toy factories for so long that it would become obvious we weren't growing older. Anyone employed for ten years or so was given a generous pension and, if he or she still wanted to work, help finding a new job. Of course, Leonardo's inventions included some remarkable machines that helped us make toys at a more rapid rate than was possible anywhere else, but this was the result of science, not magic. We asked our employees not to talk much about the toys they helped craft and, mostly, everyone obeyed this rule, especially since their pay was so good and they were treated with such respect by Arthur.

Whenever I was in London, I enjoyed visiting with these employees, chatting with them about their families. So in 1634 when Pamela Forrest asked if I could spare a moment, I was glad to do so. Pamela was in her late twenties and we often spoke about her two sons and her husband, Clive, a London barber. Poor people trimmed their own hair with knives, but wealthier men and women enjoyed having this task done for them. Pamela, who had then worked at the toy factory for about three years, often shared funny little stories about her husband's customers, but I noticed on this occasion that she seemed very concerned about something.

“You appear upset, Pamela,” I said. “I hope nothing is wrong. Are your husband and children all right?”

Pamela Forrest

“They're fine, Layla, praise God, but I hope I haven't done something wrong,” she replied. “Now, I know none of us are to discuss what we do here, and I promise you I haven't. I'm very grateful to Mr. Arthur for the kindness and generosity he shows to all of us who work for him. But I did have a word with someone about you and your husband, Nicholas, who I've heard of but never met because he's over in the New World colonies.”

I was immediately concerned. “Who did you talk to, Pamela, and what did you tell them?”

“Only about your husband in America, ma'am, and precious little about that, because, if for no other reason, I don't know much,” Pamela answered, wringing her hands nervously. “It was all quite innocent, and quite natural. My husband, Clive, the barber, was trimming a gentleman's hair the other day, and the man told him he was thinking of going to America as a colonist because he found living here so distasteful.”

“I know some people do, Pamela,” I said. “Please continue.”

“Well, this gentleman is a good customer of Clive's, and as it happens I also know his wife, who I meet now and then in the market. Her name is Elizabeth and she's a lovely lady. Well, her man told mine about maybe going to the colonies, and then I met Elizabeth yesterday and she said she was frightened by the thought, that to her mind all there was across the ocean was starvation and attacks by the natives. Well, you get letters from your husband who's there, and I thought perhaps you could talk to Elizabeth and her husband about what it's really like. I hope I haven't made you angry. I'm just trying to help my friend.”

I felt quite relieved. After fourteen years in the New World, Nicholas's letters were increasingly positive. He still disdained the Puritan settlers and their refusal to celebrate Christmas, but both he and Felix felt quite at home with the Dutch and their continued enjoyment of visits from St. Nicholas. In fact, Nicholas had begun urging me to cross the Atlantic and join him, but I was worried about Christmas in England and didn't want to leave Arthur alone to face an uncertain future.

“So long as you didn't mention our toy factory, Pamela, there's no problem at all,” I told her. “Am I to call on your friend Elizabeth and her husband? I can only tell them what Nicholas has told me, of course, but I'd be glad to be helpful if I can.”

Other books

The Stelter City Saga: Ultranatural by Stefany Valentine Ramirez

Dream Weaver (Dream Weaver #1) by Su Williams

Murder in the Mist by Loretta C. Rogers

The Man to Be Reckoned With by Tara Pammi

Unbound by Cat Miller

Never Fuck Up: A Novel by Jens Lapidus

Catch by Michelle D. Argyle

A Kind of Magic by Susan Sizemore

How Loveta Got Her Baby by Nicholas Ruddock

Tideline by Penny Hancock