How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (12 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

“This has made Nicholas and Felix so furious that they've left Plymouth and joined Dutch settlers in their colony of Fort Orange,” I told Arthur and Leonardo as I read a letter from my husband that had arrived by ship. “They say that, as awful as it sounds, Christmas has been made completely against the law in Plymouth, and celebrating it will result in severe punishment.”

“I'm sorry, but not surprised,” Arthur observed. “I suppose, in all their excitement of going to the New World, Nicholas and Felix forgot this has already happened in an entire country. Christmas has been against the law in Scotland since 1583.”

This was very sad, but still a fact. In Scotland, a nation separate from England to the north, Puritans were especially anxious to rid themselves of anything to do with the Catholic Church. Christmas, their leaders insisted, was more than just a bad Catholic name for a holiday. In fact, when people celebrated Christmas with singing and dancing and feasting, they violated the way Puritans thought Jesus should be worshipped. They felt people should sit quietly and think about all God's blessings, especially sending his son among us. And choosing December 25 as Jesus' birthday was, to their minds, an insultâJesus was better than any ordinary person, and only ordinary people had birthdays. They were certainly entitled to these opinions, but they wanted everyone to share them. So the Scottish Puritans and elected leaders made celebrating Christmas a crime. And, as Arthur pointed out, if it happened in Scotland, it could certainly happen in England.

“Our current King James ruled in Scotland before Queen Elizabeth of England died without children in 1603,” he reminded me. “So James has allowed Christmas to be banned in one country already. Puritans don't yet control government in England, but they are louder than anyone else, and if they ever are in charge I suspect Christmas will be the first target of their wrath.”

“Christmas means too much to too many people in this country,” I said firmly. “For poor families in particular, December 25 is the only day of the year when they can feast and dance and sing and forget, for just a little while, how hard they have to work, and how little they have to call their own. It's just a different way of thanking God for Jesus than sitting quietly in a room, thinking. I can't believe the Puritans want to prevent others from having a little holiday happiness.”

Arthur's eyes narrowed, and he looked quite grim.

“Layla, we've both lived long enough to realize something,” he said. “There are always those who want to control the way everyone else lives, including how, when, and why they are happy.”

“Well, the Puritans have picked the wrong place for a fight over Christmas,” I replied. “No country celebrates Christmas better than England. Of course, no country needs Christmas more, either.” Then, upset at the possibility of the holiday being taken away, I donned my cloak and hurried outside. I walked for hours through the London streets, and everywhere I looked I was reminded why the ordinary people of Britain should not be deprived of their beloved holiday.

The London where Arthur and I fretted about the Puritans and Christmas almost four hundred years ago was a much dirtier, desperate place, where most citizens lived in poverty and seldom survived past the age of fifty.

CHAPTER

Six

Six

Â

Â

Â

Â

L

ondon in the 1600s was nothing like the sprawling city we know today. Because some of its very oldest buildings and monumentsâParliament, the Tower of London, some castles and mansionsâstill stand, many people think the city hasn't changed very much. But it has. The London where Arthur and I fretted about the Puritans and Christmas almost four hundred years ago was a much dirtier, desperate place, where most citizens lived in poverty and seldom survived past the age of fifty. A few rich people enjoyed lives of luxury, living in fine homes and riding everywhere in gilded, horse-drawn carriages. Almost everyone else, including many children, labored for little pay at difficult, physically demanding jobs and went home to dark, damp huts at night with nothing to look forward to but a supper of scraps and then a few hours of sleep before they had to get up and do the same discouraging things all over again.

ondon in the 1600s was nothing like the sprawling city we know today. Because some of its very oldest buildings and monumentsâParliament, the Tower of London, some castles and mansionsâstill stand, many people think the city hasn't changed very much. But it has. The London where Arthur and I fretted about the Puritans and Christmas almost four hundred years ago was a much dirtier, desperate place, where most citizens lived in poverty and seldom survived past the age of fifty. A few rich people enjoyed lives of luxury, living in fine homes and riding everywhere in gilded, horse-drawn carriages. Almost everyone else, including many children, labored for little pay at difficult, physically demanding jobs and went home to dark, damp huts at night with nothing to look forward to but a supper of scraps and then a few hours of sleep before they had to get up and do the same discouraging things all over again.

Four million people lived in England then, and about two hundred and fifty thousand of them were in London, making it by far the largest city in the country. It was one of the oldest, too, originally built as a fort and supply depot by the Romans in 43 A.D. on the south bank of the River Thames, a mighty waterway. When the Romans left four hundred years later, the Saxons gradually took it over, and then the Normans. It became clear that whoever ruled England would do so from London.

That meant the city attracted lots of people, starting with the lords and ladies who made up the royal court. They wanted great houses of stone and later brick to live in, and servants to tend to their needs. Building materials and food and clothing had to be supplied by merchants, who made up a sort of in-between social class. They, in turn, needed people to build their shops and the much more modest homes middle-class families lived inâhouses cobbled together from wood and plaster, not more expensive stone. Still others were needed to prepare the food and sew the clothing the merchants sold to the rich, and these workers were paid very small salariesâpennies every week, not every dayâand their homes were really tiny huts, often with thatch roofs that would burn far too easily. And so the population of London always grew, with dozens of very poor people added for each rich one.

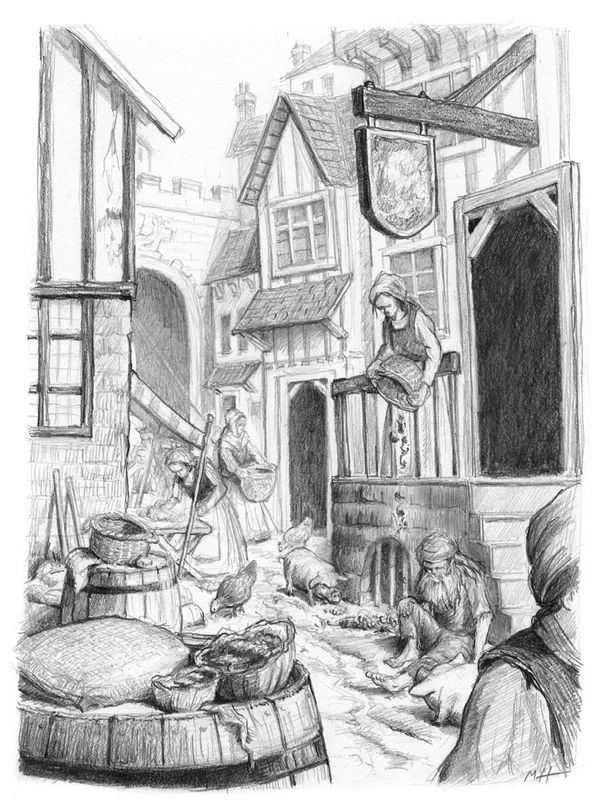

I walked through London after my conversation with Arthur. It was late November in 1622. Nicholas and Felix had been in America for almost two years. I missed my husband terribly, and, of course, I missed Felix, too. But as I walked, my thoughts were about the people and places I was seeing. What a difference there was between the lives of the rich and poor! Most of London's streets were narrow and dirty. A few avenues were paved with cobblestones, but these were the ones that led directly to the fine mansions. Everyone else walked to and from their homes and jobs on paths of dirt. When it rained, the mud was ankle-deep. During dry weather, dust blew up into everyone's eyes, noses, and mouths. Garbage was everywhere. There were no organized pickups of trash. If you were lucky enough to have an apple to eat and not so hungry that you'd gulp down every bit of it, including the stem and seeds, then you'd toss the core into the street. It would lie there, swarming with flies, until it rotted away, or until it was gobbled by one of the hundreds of pigs that waddled around loose. Stray dogs and cats roamed everywhere, too, fighting beggars and cripples for bits of bread or cheese tossed from passing carriagesânot in charity, usually, but by someone riding along in comfort who'd eaten his or her fill and was discarding the leftovers. And rats ate whatever the humans and other animals somehow missed.

As I approached the Thames, I saw that, as usual, its banks were lined with fishermen. The wide river teemed with salmon, trout, perch, and eels. Those who traded in seafood had boats and nets; they could go out in the deepest parts of the river and often haul up a bountiful catch. Common folk who would either catch a fish or go hungry that night often had one poor line to toss in the water, its hook baited with a bit of animal fat. There were at least enough fish in the Thames that they had a good chance of landing their supper. Several times, in fact, whales were spotted, though the last of these was reported in the 1400s.

Food was of constant concern to all but the very rich. Meat came with most meals only in the mansions, where five or six courses might be served as dinner, accompanied by expensive wine. In the small cottages and fragile huts, porridge or bread smeared with lard frequently made up the entire menu. Vegetables grown in tiny garden plots were considered treats. When potatoes were introduced to England and Ireland from Peru in the late 1500s, these became another diet staple. If there was anything besides water to drink, it might be cheap, weak beer, which was shared by children as well as adults. Poor people seldom left their tables feeling comfortably full, only less hungry.

The rich and poor dressed quite differently, too. Wealthy people wore clothing made from cotton and silk, with lots of lace sewn on.

They had plenty of shirts and dresses. These well-to-do men and women often wore elaborate wigs, and their shoes were shiny because they seldom had to step in the dirty streets. Their carriages whisked them wherever they wanted to go. Poor people wore mostly woolen clothes, and didn't change them often because they had no other clothes to put on. And, while the clothing of the rich came in all colors of the rainbow, the poor would try to brighten their drab garments with bright vegetable dyes, and, when it rained, these often ran and stained their arms and legs.

The London I wandered was, quite frankly, a smelly place. This wasn't just caused by the garbage and the animals on its streets. Rich or poor, few people bathed very often. Water was difficult to come by. You could haul buckets of it from the river, but even in the 1600s people realized much of the water there was fouled with garbage. There were places in the city where you could buy barrels of clean water, but this kind of purchase was well beyond the means of most. Water bearers sometimes passed along the streets, selling smaller quantities for a few farthings, but with money needed for food and clothing, buying water for washing was too much of an extravagance. And, though it's not pleasant to think about, there was no indoor plumbing either. Rich people had chamber pots, poor people just plain pots. After they were used, they had to be emptiedâoften in the same streets where everyone walked.

For entertainment, rich people in London could have parties and dances whenever they liked. They often had country estates where they could ride horses or stroll through flowery meadows if they grew tired of the city crowds and smells. Everyone else had more limited choices. Many poor people couldn't read, and for those who could, books were both rare and expensive. Under the best of circumstances, they might make an occasional visit to a theater. There were plays to see. King James, among others, had encouraged a playwright named William Shakespeare. You could enjoy dramas and comedies for a penny, though at that price you had to stand up the whole time in a crowded area in front of the stage, while those who could afford more expensive tickets sat in nice chairs on elevated platforms. And the working class enjoyed sports, too. Some, like cock-fighting, where roosters were encouraged to attack each other, or bear-baiting, which is exactly what its name describes, were cruel beyond modern belief. But others would be familiar to almost anyone todayâfootball, for instance, which in America is better known as soccer. Football was by far the most popular sport because you didn't need much to play it, just a ball (perhaps a blown-up pig's bladder, or something of that sort), two areas designated as goals, and players with enough energy to run around for a while.

Mostly, though, nine out of every ten people in 1600s London worked hard every day with very little to show for it. Religion, which should have been a comfort, hadn't been much of one since King Henry VIII abruptly left the Catholic Church a century earlier. Ever since, there were confusing, constantly changing rules about how everyone could worship. During the reign of Queen Mary, some Protestants had even been burned at the stake. Now King James supposedly would allow anyone to worship as he or she pleased, but everyone remained afraid that the rules would change again without notice, and they might be in danger because of how they chose to practice their faith. Always, too, there was the threat of war to further complicate things. When England wasn't enduring civil war, its leaders were generally embroiled in battle against foreign foes, most often the French. In matters of daily life, in religion, in national issues, all the poor people of England felt little but stress or even fear. Their opinions didn't count. Nobody powerful really cared what they thought or what they wanted. Their monarch James firmly believed in the divine right of kingsâif God allowed someone to be a king, then whatever the king wanted must be God's will, and no one was allowed to disagree. Perhaps the hardest thing for poor people was knowing there was nothing most of them could do to improve their lives. If you weren't born rich, there was little chance you could become wealthy. Property and titles were handed down from one generation to the next. Working-class people had no chance to acquire such things.

But they also had one time each year when all this could be put aside, a time when the most poverty-stricken families could expect that their rich employers would be generous, even thoughtful, to them. That time, of course, was Christmas, and as I walked through London on this early winter evening I smiled as I spied several people already festooning the doors of their humble cottages with holly and green boughs, two popular decorations at holiday time. Of course, the source of this pleasant tradition originally came from earlier, non-Christian faithsâin the winter, primitive people would set out greenery as a sign they believed spring would come againâbut now they were just tokens that almost everyone was preparing to celebrate the birth of Jesus.

Other books

On Distant Shores by Sarah Sundin

Trapped In Shadow (Shadow Walker Romance Series Book 4) by Caryn Moya Block

Moon Mirror by Andre Norton

Another Dawn by Deb Stover

One Way (Sam Archer 5) by Barber, Tom

A Boy in the Woods by Gubin, Nate

River Deep by Rowan Coleman

Open Your Eyes by Jani Kay

The Truth of All Things by Kieran Shields

Narrow Dog to Carcassonne by Darlington, Terry