How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (34 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

Alan squirmed over to Elizabeth's side. Because his hands were tied he couldn't put his arm around her, but he leaned so that their shoulders touched.

“Don't be afraid, love,” he said softly. “I don't think they'll do anything too terrible to us.”

“You don't believe that for a moment, and I'm not crying about our predicament,” Elizabeth replied. “I'm afraid for Sara. She's all alone at the cottage, and both her parents are prisoners.”

Panic shot through me. I had forgotten about Sara. I wondered how long she would sit up waiting for us to return. Maybe, after hours and hours, she would come to the barn herself to see what was delaying us. Culmer might take her prisoner, too! “Don't mention Sara,” I hissed to Elizabeth. “If Culmer overhears, he might send his men to arrest her, too, just to make you and Alan feel even worse. She 's Sophia's best friend. I don't think Margaret Sabine will let anything bad happen to her. But don't talk about Sara now!”

The four of us talked quietly a little longer. We thought it odd that Culmer was not questioning us about others involved in the Christmas Day protest plan. It was as though he didn't care. Why? And why were we being kept in the barn until dawn? After a while, Elizabeth and Alan, exhausted by fear and stress, dozed. Arthur and I remained awake. Every so often I would glance over at Blue Richard Culmer, who leaned back against the hay bale smoking his pipe and never taking his eyes off of us. Finally, as the first faint streaks of dawn appeared on the eastern horizon, Culmer stood up, stretched, and nodded to one of the Trained Band. That fellow went to a far corner of the barn and, with some effort, picked up a heavy canvas bag that clanked as he carried it over to where we four prisoners sat. The clanking woke Alan and Elizabeth.

“Chains,” Arthur said grimly, and he was correct. “Now, I understand. Culmer means to make examples of us.”

“Exactly, Mr. Arthur,” Culmer snarled. “Men, secure them properly, and take no chances. Keep those ropes tight around their arms until all the chains are in place.”

It was horrible. The chains were very heavy. Manacles were snapped around our wrists, which were still kept behind our backs. Then lengths of chain were placed around all of our waists, with about two feet of additional chain linking us up one to anotherâme to Arthur, Arthur to Elizabeth, and Elizabeth to Alan. Finally, Culmer stepped up and personally secured a final shackle around my neck, much like a master will place a collar and leash on a dog. “Time to go to town,” he crooned, and tugged the length of chain attached to my neck. I was jerked forward and forced to follow him, and my three friends staggered along behind me in a grotesque parade. The Trained Band soldiers took up their muskets and fell in on either side of us. “Slowly, now,” Culmer cautioned as he led the way down the hill. “Don't stand too close to the prisoners, lads. We want all their friends and neighbors to get good looks at them!”

Country people around Canterbury rose with the sun, so as we reached the main path toward town there already were many people moving along it. As we made our ghastly walk, I recognized quite a few of themâthey were all participants in the planned protest. Now their eyes widened and their mouths fell open in shock to see their leaders in Blue Richard Culmer's clutches.

“See what happens to Christmas plotters?” Culmer bellowed over and over as we made our slow, awful way into Canterbury. “All those who unlawfully celebrate Christmas face swift and certain punishment! Would you want this to be

you

?” People who had greeted me every day for five years turned away, trying not to look me in the eye. Culmer was using us to frighten the rest of the people into submission, just as he had used the smashing of cathedral stained-glass windows a few years earlier. And his plan was obviously working. No one called out comforting words to us; onlookers were too afraid for their own safety to offer any show of support.

you

?” People who had greeted me every day for five years turned away, trying not to look me in the eye. Culmer was using us to frighten the rest of the people into submission, just as he had used the smashing of cathedral stained-glass windows a few years earlier. And his plan was obviously working. No one called out comforting words to us; onlookers were too afraid for their own safety to offer any show of support.

Culmer led us into Canterbury through St. George's Gate on the eastern wall, and the guards there snapped to attention and saluted him as we passed. High Street, the main city thoroughfare that was lined with shops, ran straight through the center of Canterbury and ended at the West Gate, with its two hulking towers, one of which housed the city dungeon. Culmer obviously intended to take us there, but along the way he wanted as many people as possible to see us in our chains. We tried to walk with some dignity, but with our hands chained behind us it was hard to do. Every so often Culmer would deftly tug at the chain linked to my neck, and I would stumble a little, and in turn Arthur, Elizabeth, and Alan would be pulled off balance and stagger for a few steps. Right through the central marketplace he led us, calling out for the Trained Band soldiers to make the crowd stand clear. As word of our procession spread, black-cloaked Puritans began to appear all along High Street, calling out insults to the four of us and jeering that Christmas was gone forever, and look at the dreadful fate we'd brought on ourselves by not accepting that! I was terribly afraid, though not for myself. I was thinking about Sara. When she woke and discovered that her parents and auntie hadn't returned to the cottage, what would she do? The girl was so shy that she would probably not run to a neighbor and ask for help. Perhaps she'd make her way into Canterbury and her friend Sophiaâwhat if my darling girl was seeing us in chains right now? I began desperately looking at the people lining both sides of the street, my head swiveling back and forth, and Blue Richard Culmer saw me and misunderstood.

“You're feeling panic, I can tell!” he crowed. “Well, missus, not one of those people is going to help you, so there's no sense searching for a friend. You have no friends left!”

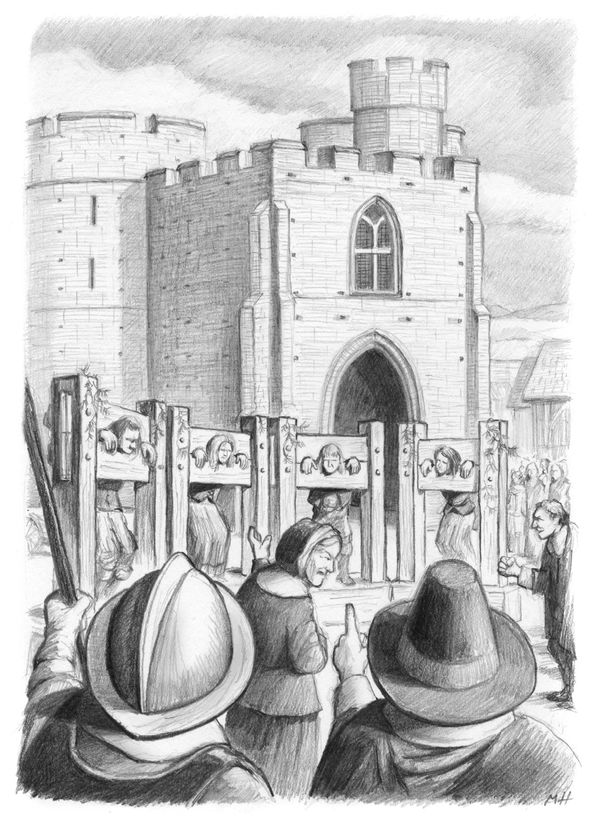

We finally reached the West Gate, where the north tower served as the town prison. I thought Culmer would immediately throw us into cells, but he had other plans. Outside the tower were four sets of “stocks,” wooden stands with openings that closed around prisoners' necks and wrists, forcing them into an awkward standing crouch until, finally, the stocks would be unlocked and they could move around again. Culmer ordered us locked into these stocks. Hundreds of people gathered about; criminals were usually put into the stocks for extra embarrassment after some particularly disgusting crime, like stealing from church coin boxes. Then Mayor Sabine appearedâI could only see him out of the corner of my eye, because the stocks were tight and I could not move my head.

“Behold the Christmas criminals!” Sabine roared to the crowd. “This is what happens to traitors who plan riots on behalf of sinful holidays! These evildoers hoped to lead many of you into crime, but your mayor and Mr. Culmer have saved you! Look on them, and learn your lesson! There is no longer any Christmas in England, or in Canterbury!” Then Culmer directed the Trained Band soldiers to festoon the stocks with green boughs and holly, in a mockery of traditional Christmas decorations. There was nothing for Arthur, Elizabeth, Alan, and me to do but stand where we were locked in place as the sun traveled across the winter sky. All day, we were offered no food or water, and all of us were feeling weak when, in early evening, Culmer finally ordered us taken out of the stocks. Our legs were so stiff that we staggered as, at gunpoint, we were marched into the jail. Down stone steps we went, until, finally, we came to a heavy, barred door, which creaked ominously as it was opened and we were forced inside. The stone walls of this dungeon were damp and reeked of rot.

“There are empty buckets for you when you need to do the obvious,” Culmer said. “Bread and water will be brought in the morning. By then you'll be so hungry, you'll think you're dining on fine holiday goose. In the meantime, why don't you pray to Father Christmas? Perhaps he'll come to save you.” Then Culmer stepped back and nodded to a jailer, who grunted as he swung the heavy cell door shut. The single lantern lighting the hallway was extinguished, and we were prisoners in the dark.

We were brought outside in the cold morning light. Our appearances, I know, were appalling. Our clothes were nasty and torn, our exposed skin was filthy, and our legs so weak we could barely stand as we were locked into the stocks.

CHAPTER

Twenty-one

Twenty-one

Â

Â

Â

Â

W

e only knew it was morning when two jailers lumbered If down the stone steps to our dungeon cell carrying a bucket of water and two loaves of stale bread. One stood outside with a musket and torch while the other unlocked the heavy door, growled “Breakfast,” shoved the bucket and bread inside, then slammed the door shut and locked it again. The only light we had came from the torch, and it was a relief when the second jailer jammed it into a holder on the wall outside the cell and we could see a little by the flickers it cast through the barred window. As the jailers went back up the steps without another word, we took turns having long sips from the bucketâthe water was sour tasting, and I tried not to think of where it might have come fromâand then Arthur insisted we each eat some bread. None of us felt especially hungry, despite the fact we hadn't had a meal since noon the day before. Our troubles had overwhelmed our appetites. But Arthur pointed out we needed to keep up our strength, so we ate.

e only knew it was morning when two jailers lumbered If down the stone steps to our dungeon cell carrying a bucket of water and two loaves of stale bread. One stood outside with a musket and torch while the other unlocked the heavy door, growled “Breakfast,” shoved the bucket and bread inside, then slammed the door shut and locked it again. The only light we had came from the torch, and it was a relief when the second jailer jammed it into a holder on the wall outside the cell and we could see a little by the flickers it cast through the barred window. As the jailers went back up the steps without another word, we took turns having long sips from the bucketâthe water was sour tasting, and I tried not to think of where it might have come fromâand then Arthur insisted we each eat some bread. None of us felt especially hungry, despite the fact we hadn't had a meal since noon the day before. Our troubles had overwhelmed our appetites. But Arthur pointed out we needed to keep up our strength, so we ate.

“I must know what's happened to Sara,” Elizabeth moaned after she reluctantly gulped down a few mouthfuls of the awful loaf. “Surely someone has found her by now.”

“I'm certain the Sabines have brought her to their home,” Alan said reassuringly, though I could tell he was not as confident as he was trying to sound. “These people might have arrested us for trying to save Christmas, but they surely won't punish an innocent child.” He chewed on his bread for a few moments and then asked, “What do you think they will do to us today?”

“Probably nothing,” I said. “Culmer knows it is much more cruel to leave us here for a while wondering about his intentions before revealing them. Meanwhile, we'd better save what's left of the bread and water. It may be all we get for a while.”

I was right. No one came down the stairs to our cell. Sometime during the day the torch went out, and we were plunged back into total darkness. The hours crawled by. I knew Alan and Elizabeth were tormented by their fear for Sara, and I felt the same. Arthur undoubtedly was devising escape plans, though nothing of the sort seemed possible. There was only the one door to our cell, and the narrow stone stairway leading up from it was undoubtedly guarded at the top. None of us speculated what Blue Richard Culmer and the Puritans might have in mind for our further punishment. Anything was possible. They could twist the laws in any way they pleased to suit themselves. We talked very little, because we were so discouraged and also because Arthur warned there might be some jailer perched on the stairs hoping to overhear information about the protest plan that he could report back to Culmer.

“We have to protect everyone else if we can,” Arthur whispered. “I believe Janie only identified the four of us. With luck, all our captains and other supporters might be spared.”

“Perhaps they'll march anyway, even though we've been taken prisoner,” Alan said hopefully.

“That would surprise me,” I replied. “You saw how everyone remained silent when we were pulled down High Street in chains. An effective protest needs leaders, so even if some of them do try to march without us on Christmas Day, they'll be confused and easily dispersed by Sabine and the Trained Band.” As soon as I spoke these gloomy words, I regretted them. Our situation was bad enough without adding to it. So I didn't say anything more, and neither did the others. After a while I began thinking about my husband. I knew Nicholas was far across the ocean, preoccupied with bringing Christmas gifts to colonial children in the New World. How many more months would it take before he noticed there had been no letters from Arthur or me, and what would he do when he learned of our fate, whatever it might turn out to be?

I suppose all of us slept a little, though afterward it seemed to me I hadn't closed my eyes at all when the rattle of boots on stone steps indicated another day had passed. A new torch flared its light into our cell, and when the heavy door was unlocked and swung open, there stood Blue Richard Culmer.

“How are my guests this fine morning?” he jeered. “How wonderful you all look.” This, of course, was sarcasm. All four of us were dirty from sprawling on the cell floor, and smelly from not bathing. After so many hours spent in darkness, even the feeble torchlight made us blink and rub our eyes.

“What do you mean to do with us, Culmer?” Arthur demanded. “You can't keep us prisoners without telling us what we're charged with and allowing us a fair trial on those charges.”

Culmer emitted his usual odd cackle. “You don't understand our special new laws. In emergency situations dealing with obvious traitors, we can keep prisoners as long as we like without going through the usual motions of charges and trials. We decent English people are at war with sinners like you, and so you have no legal rights. But of this, you may be certainâfor planning a violent riot in support of the illegal Christmas holiday, your punishment will be quite severe. Well, I'll leave you to wonder what will happen to you. Now that you're in custody, I'm off to London. We've heard rumors of Christmas plotters there. Please continue to make yourselves at home. Bread and water will be served soon.”

Other books

blood 03 - blood chosen by tamara rose blodgett

Charred by Kate Watterson

Unexpected Chance by Annalisa Nicole

The Haunting of James Hastings by Christopher Ransom

Viper Team Seven (The Viper Team Seven Series Book 1) by Lewis, Rykar

Can't Keep a Brunette Down by Diane Bator

Margaret Moore - [Warrior 13] by A Warrior's Lady

Isle of Mull 03 - To Love a Warrior by Lily Baldwin

Pay It Forward by Catherine Ryan Hyde

The Dread Wyrm (Traitor Son Cycle) by Miles Cameron