How They Started (23 page)

Authors: David Lester

The “healthy” positioning of Chipotle’s food has also come under fire. The Center for Science in the Public Interest has pointed out that with over 1,000 calories, a giant Chipotle burrito is essentially two meals’ worth of food. But the negative flak Chipotle has received has made no dent in public enthusiasm for the chain’s cuisine.

Where are they now?

By August 2011, Chipotle’s stock had grown by more than 500 percent since its IPO in 2006, to nearly $290 a share. The restaurants serve about 800,000 customers per day and take in an average of about $2 million apiece. The company saw more than 10 consecutive years of double-digit growth in comparable-store sales that ended only with the 2008 recession, and by early 2012 it had recovered to see six consecutive quarters of positive same-store sales growth. In 2011, Chipotle ranked #54 on

Fortune

magazine’s list of the 100 fastest-growing companies. In 2010, Steve’s own pay topped $14 million in cash and stock.

As Chipotle’s success grew, Steve became more involved in philanthropy around his pet cause: sustainable, organic food. Over the last couple of years, the company gave over $2 million to organizations including The Nature Conservancy, Jamie Oliver’s Food Revolution, Family Farmed.org, and the Niman Ranch Scholarship Fund. The Chipotle Cultivate Foundation was established in 2011 to continue this work.

Rather than putting energy into a big, international rollout of Chipotle, the company has focused on creating a second fast-casual concept that could duplicate Chipotle’s American success. ShopHouse Southeast Asian Kitchen offers Thai, Vietnamese and Malaysian cuisine, while employing Chipotle’s fresh-and-natural ethos and production-line delivery methods.

The ShopHouse name was registered in early 2011, and the first restaurant opened in September 2011 in Washington, DC. The name came from inspiration Steve found from trips abroad, eating in Asian shophouses, a style of family business in which the owners operate a business on the ground floor of a two-story building and live upstairs. The staple menu items are “bowls” and Vietnamese-style baguette sandwiches known as

bahn mi

, seasoned with a choice of mild or spicy curry sauce or a tamarind vinaigrette. As at Chipotle, customers can customize their order as they move down the service line.

“I always believed that the Chipotle model would work well with a variety of different cuisines,” Steve said at the announcement of ShopHouse. “Chipotle’s success is not necessarily about burritos and tacos, but rather about serving great, sustainably raised food that is delicious, affordable, and convenient.”

Making liquid gold out of dehydration

Founders:

Robert Cade, Dana Shires, Harry James Free and Alejandro de Quesada

Age of founders:

37 (Robert)

Background:

Medicine

Founded in:

1965

Headquarters:

Chicago, Illinois

Business type:

Sports drink

Gatorade is now a PepsiCo “mega brand”

generating $7 billion in annual sales for the drinks giant; but it wasn’t always the case. Spin back to the 1984–85 NFL season. There were high expectations for the 2012 Super Bowl-winning New York Giants that year too. But a third of the way into their schedule, the Giants stood at a mediocre 3-3 record. Then a curious thing happened. After beating their archrival the Washington Redskins, the Giants’ nose guard Jim Burt picked up the team’s cooler of Gatorade as the game clock expired and poured it over head coach Bill Parcells.

Fans, teammates and media were shocked. Most saw it as a sign of disrespect. In fact, it was just a bit of playful revenge on Burt’s part after Parcells had chided him all week that he would struggle against the Redskins’ offensive line. But it was also intended as a celebration of the team’s success.

Luckily for Burt, Parcells had a sense of humor and smiled as he was showered with the energy drink. And when the Giants won again the following week, Burt persuaded teammate Harry Carson to join him in another Gatorade bath. Because Parcells was known for being quite superstitious, the dunks continued. And the Giants had thus initiated a celebration that defied the traditional boundaries of coach and player. Little did they know then what an impact it would have on Gatorade and the wider world of sports.

The following season, as the Giants stormed to their eventual Super Bowl win, the media followed the unique tradition of soaking coach Parcells in a “Gatorade bath.” Suddenly a sports drink was overshadowing their wins. Games were being watched just for that moment when the cooler was tipped over Parcells’s head.

The tradition soon spread across professional and amateur sports alike. There it was, at the end of every broadcast game, a Gatorade-branded cooler hefted over the coach’s head. And so in perhaps the most remarkable example of viral advertising in corporate history, what began as a little-known sports drink developed on a tiny budget in its creators’ spare time grew into a dominant global brand with a name synonymous with success.

The Gatorade story has its roots in the 1960s, when the University of Florida freshman football squad was having a tough time. In August 1965, 25 of the first-year Gators were admitted to the university’s hospital with dehydration and heat exhaustion. In fact, this was a nationwide problem, as late-summer heat claimed the lives of a number of young football players. Dewayne Douglas, an assistant coach for the Gators, mentioned his concerns to his friend Dr. Dana Shires, a research fellow at the University of Florida who worked under 37-year-old associate professor of medicine Dr. Robert Cade.

Douglas spoke to Dana about his team’s troubles. Even those who weren’t becoming ill were suffering. Some tried to rehydrate by drinking lots of water, but were experiencing stomach cramps. Those who consumed too much salt got leg cramps. A desperate Douglas asked if Robert and his team could look into why so many of his players were suffering from heat-related illnesses.

As a specialist in kidney disease, Robert had a lot of experience in mixing rehydration solutions, and though he had other priorities at the time, he agreed to investigate the matter. Joining Robert and Dana were fellow researchers Dr. Harry James Free and Dr. Alejandro de Quesada, the latter having recently arrived from Cuba with just $5 to his name. To the four of them, Douglas’s request was intriguing for the riddle that it posed; not one of them dreamed they would get rich from their little side project.

Robert and Dana began by focusing their attention on the composition of sweat. Not much was known about it at the time, but after several months of research Robert and his team determined that the players were losing electrolytes and carbohydrates that weren’t being properly replenished. Using these findings, they then spent $43 developing a beverage containing sodium and potassium that would move through the body quickly to help re-balance the players’ carbohydrate and electrolyte levels. To make it tolerable to drink, the doctors squeezed 20 lemons into the concoction, on Robert’s wife’s recommendation.

But developing the drink was in some ways the easy part. Next the team had to convince the Gators’ head coach and athletic department to let them test it on the players. They faced a prevailing attitude of “tough it out” in those days. Many teams didn’t even provide water on the sidelines, instead believing that dehydration would toughen up their players.

Joining Robert and Dana were fellow researchers Dr. Harry James Free and Dr. Alejandro de Quesada, the latter having recently arrived from Cuba with just $5 to his name.

Thankfully Gators’ coach Ray Graves didn’t subscribe to this school of thought, having endured it himself as a player two decades prior. Graves didn’t understand the science Robert and his team pitched to him, but he agreed to try it nevertheless.

With the coach’s blessing, Robert and his team recruited two freshmen to be their guinea pigs. After their two-hour practice sessions, they would accompany Robert back to the lab where the researchers took blood and urine samples, recorded body temperatures and analyzed sweat wrung from the players’ gloves. In return, Robert took the players out for a steak dinner—the only major development cost Robert incurred, as everything else was done in the university lab.

Soon they began giving the drink to all the freshman players, and as a sort of test, the freshman team played the varsity squad. The freshmen drank the researchers’ concoction on the sidelines, while the varsity team drank water. As expected, the more experienced varsity team jumped to a quick lead. But then something quite intriguing happened. The varsity team wore down as the game went on, but the freshmen maintained their stamina and ended up winning.

Impressed, Coach Graves asked the doctors if they could make a batch for the entire varsity team, which was set to play the heavily favored Louisiana State University Tigers the next day. The doctors stayed late in the lab that night making 100 liters of their potion, and the next day the Gators roared to an improbable 52–14 victory.

They called it Gatorade. All season long the Florida Gators consistently outlasted their opponents and beat teams they weren’t supposed to beat. The University of Florida athletic department paid Robert and his team $1,800 to compensate them for the steak dinners and all the late nights.

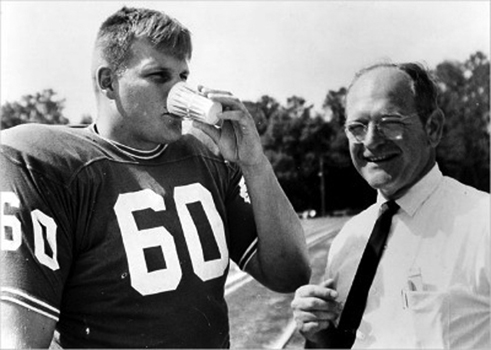

Founder Robert Cade with an athlete enjoying the promising drink.

Before this point, neither Robert, Dana, Harry nor Alejandro had thought of their concoction as anything more than a little side project that, as sports fans, they enjoyed doing in their spare time. But now Robert began to wonder if Gatorade had commercial value. When the 1966 season started he told Graves he would again produce the drink for the team, but it would cost $5 per gallon. Graves said this was too high. But two days later when 24 of his varsity players were hospitalized with dehydration, he put in a call to Robert.

“Coach Graves called my house and told my wife that he needed Gatorade at whatever cost for both games and practice,” Robert recalled. “So I told him he could have it at $10 a gallon.”

Surprised to find himself in the position of a businessman, Robert next approached the university and asked if it would like to buy Gatorade from him, or perhaps give him $10,000 to keep the product coming. The university declined; however, administrators gave Robert the green light to continue developing it on his own. And so he did.

Robert borrowed $500 from a local bank in 1966, which he used to make several hundred gallons of the drink. At the same time the Gator football team was performing even better than the previous year. Like any good secret, eventually word of Gatorade made it out of Gainesville, Florida. The media caught wind of the Gators’ advantage over opponents. And then Robert realized: it was time to grow the business.

By the time the University of Florida’s stunning 1966 season ended with an Orange Bowl victory (which the team publicly credited to Gatorade) a number of copycat products were being produced. Robert sought the services of a lawyer, who helped register a patent for Gatorade’s recipe and trademarked its name. The four doctors also filed articles of incorporation in Florida under the name Gatorade Inc., listing each of them as a director.

Orders soon came in from other universities, and for the first time Robert began bottling his drink and brokered a deal with Greyhound to ship it out on the company’s buses. He also began giving Gatorade away for free to well-known athletes as a means of getting free publicity.

It was around this time that Gatorade attracted the attention of a Northern company more famous for its cans of Pork & Beans. In 1967, one of Robert’s interns left to take a job at Indiana University, where he befriended a vice president of the Indianapolis-based Stokely-Van Camp Co., famous for its canned foods. Alfred Stokely, chairman of the company, was intrigued by Gatorade after watching the successes of the University of Florida’s athletic teams. He agreed to a meeting with Dana and the former intern, Kent Bradley.