How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine (21 page)

Read How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine Online

Authors: Trisha Greenhalgh

Question Five: What outcome measures were used, and were these sensible?

With a complex intervention, a single outcome measure may not reflect all the important effects that the intervention may have. While a trial of a drug against placebo in diabetes would usually have a single primary outcome measure (typically the HbA1c blood test) and perhaps a handful of secondary outcome measures (body mass index, overall cardiovascular risk and quality of life), a trial of an educational intervention may have multiple outcomes, all of which are important in different ways. In addition to markers of diabetic control, cardiovascular risk and quality of life, it would be important to know whether staff found the educational intervention acceptable and practicable to administer, whether people showed up to the sessions, whether the participants' knowledge changed, whether they changed their self-care behaviour, whether the organisation became more patient-centred, whether calls to a helpline increased or decreased, and so on.

When you have answered questions one to five, you should be able to express a summary so far in terms of population, intervention, comparison and outcome—although this is likely to be less succinct than an equivalent summary for a simple intervention.

Question Six: What were the findings?

This is, on the surface, a simple question. But note from Question Five that a complex intervention may have significant impact on one set of outcome measures but no significant impact on other measures. Findings such as these need careful interpretation. Trials of self-management interventions (in which people with chronic illness are taught to manage their condition by altering their lifestyle and titrating their medication against symptoms or home-based tests of disease status) are widely considered to be effective. But, in fact, such programmes rarely change the underlying course of the disease or make people live longer—they just make people feel more confident in managing their illness [8] [9]! Feeling better about one's chronic illness may be an important outcome in its own right, but we need to be very precise about what complex interventions achieve—and what they don't achieve—when assessing the findings of trials.

Question Seven: What process evaluation was done—and what were the key findings of this?

A process evaluation is a (mostly) qualitative study carried out in parallel with a randomised controlled trial, which collects information on the practical challenges faced by front-line staff trying to implement the intervention [10]. In the study of yoga in diabetes, for example, researchers (one of whom was a medical student doing a BSc project) sat in on the yoga classes, interviewed patients and staff, collected the minutes of planning meetings and generally asked the question ‘How’s it going?'. One key finding from this was the inappropriateness of some of the venues. Only by actually being there when the yoga class was happening could we have discovered that it's impossible to relax and meditate in a public leisure centre with regular announcements over a very loud Intercom! More generally, process evaluations will capture the views of participants and staff about how to refine the intervention and/or why it may not be working as planned.

Question Eight: If the findings were negative, to what extent can this be explained by implementation failure and/or inadequate optimisation of the intervention?

This question follows on from the process evaluation. In my review of school-based feeding programmes (see Question Four), many studies had negative results, and on reading the various papers, my team came up with a number of explanations why school-based feeding might

not

improve either growth or school performance [5]. For example, the food offered may not have been consumed, or it provided too little of the key nutrients; the food consumed may have had low bioavailability in undernourished children (e.g. it was not absorbed because their intestines were oedematous); there may have been a compensatory reduction in food intake outside school (e.g. the evening meal was given to another family member if the child was known to have been fed at school); supplementation may have occurred too late in the child's development; or the programme may not have been implemented as planned (e.g. in one study, some of the control group were given food supplements because front-line staff felt, probably rightly, that it was unethical to give food to half the hungry children in a class but not the other half).

Question Nine: If the findings varied across different subgroups, to what extent have the authors explained this by refining their theory of change?

Did the intervention improve the outcomes in women but not in men? In educated middle-class people but not in uneducated or working-class people? In primary care settings but not in secondary care? Or in Manchester but not in Delhi? If so, ask why. This ‘why’ question is another judgement call—because it's a matter of interpreting findings in context, it can't be answered by applying a technical algorithm or checklist. Look in the discussion section of the paper and you should find the authors' explanation of why subgroup X benefited but subgroup Y didn't. They should also have offered a refinement of their theory of change that takes account of these differences. For example, the studies of school-feeding programmes showed (overall) statistically greater benefit in younger children, which led the authors of these studies to suggest that there is a critical window of development after which even nutritionally rich supplements have limited the impact on growth or performance [5] [6]. To highlight another area of interest of mine, I predict that one of the major growth areas in secondary research over the next few years will be unpacking what works for whom in education and support for self-management in different chronic conditions.

Question Ten: What further research do the authors believe is needed, and is this justified?

As you will know if you have read this chapter up to this point, complex interventions are multifaceted, nuanced and impact on multiple different outcomes. Authors who present studies of such interventions have a responsibility to tell us how their study has shaped the overall research field. They should not conclude merely that ‘more research is needed’ (an inevitable follow-on from any scientific study) but they should indicate

where

research efforts might best be focused. Indeed, one of the most useful conclusions might be a statement of the areas in which further research is

not

needed! The authors should state, for example, whether the next stage should be new qualitative research, a new and bigger trial or even further analysis of data already gathered.

References

1

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be?

BMJ: British Medical Journal

2004;

328

(7455):1561–3.

2

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance.

BMJ: British Medical Journal

2008;

337

:a1655.

3

Skoro-Kondza L, Tai SS, Gadelrab R, et al. Community based yoga classes for type 2 diabetes: an exploratory randomised controlled trial.

BMC Health Services Research

2009;

9

(1):33.

4

Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial.

BMJ: British Medical Journal

2012;

344

:e3874 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3874.

5

Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes.

BMJ: British Medical Journal

2007;

335

(7625):858–61 doi: 10.1136/bmj.39359.525174.AD.

6

Kristjansson EA, Robinson V, Petticrew M, et al. School feeding for improving the physical and psychosocial health of disadvantaged elementary school children.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

(Online) 2007;(1):CD004676 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004676.pub2.

7

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care.

The Lancet

2003;

362

(9391):1225–30.

8

Foster G, Taylor S, Eldridge S, et al. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

(Online) 2007;

4

(4):1–78.

9

Nolte S, Osborne RH: A systematic review of outcomes of chronic disease self-management interventions.

Quality of life research

2013,

22

:1805–1816.

10

Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study.

BMJ: British Medical Journal

2009;

339

:b3496.

Chapter 8

Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests

Ten men in the dock

If you are new to the concept of validating diagnostic tests, and if algebraic explanations (‘let’s call this value

x

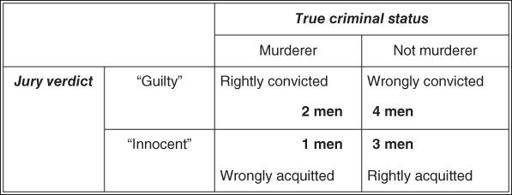

…') leave you cold, the following example may help you. Ten men (for the gender equality purists, assume that ‘men’ means ‘men or women’) are awaiting trial for murder. Only three of them actually committed a murder; the other seven are innocent of any crime. A jury hears each case, and finds six of the men guilty of murder. Two of the convicted are true murderers. Four men are wrongly imprisoned. One murderer walks free.

This information can be expressed in what is known as a

two-by-two table

(

Figure 8.1

). Note that the ‘truth’ (i.e. whether or not each man

really

committed a murder) is expressed along the horizontal title row, whereas the jury's verdict (which may or may not reflect the truth) is expressed down the vertical title row.

Figure 8.1

2 × 2 table showing outcome of trial for 10 men accused of murder.

You should be able to see that these figures, if they are typical, reflect a number of features of this particular jury.

a.

This jury correctly identifies two in every three true murderers.

b.

It correctly acquits three out of every seven innocent people.

c.

If this jury has found a person guilty, there is still only a one in three chance that the person is actually a murderer.

d.

If this jury found a person innocent, he has a three in four chance of actually being innocent.

e.

In 5 cases out of every 10, the jury gets the verdict right.

These five features constitute, respectively, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of this jury's performance. The rest of this chapter considers these five features applied to diagnostic (or screening) tests when compared with a ‘true’ diagnosis or gold standard. Section ‘Likelihood ratios’ also introduces a sixth, slightly more complicated (but very useful), feature of a diagnostic test—the likelihood ratio. (After you have read the rest of this chapter, look back at this section. You should, by then, be able to work out that the likelihood ratio of a positive jury verdict in the above-mentioned example is 1.17, and that of a negative one 0.78. If you can't, don't worry—many eminent clinicians have no idea what a likelihood ratio is.)

Validating diagnostic tests against a gold standard

Our window cleaner once told me that he had been feeling thirsty recently and had asked his general practitioner (GP) to be tested for diabetes, which runs in his family. The nurse in his GP's surgery had asked him to produce a urine specimen and dipped a special stick in it. The stick stayed green, which meant, apparently, that there was no sugar (glucose) in his urine. This, the nurse had said, meant that he did not have diabetes.