Human Trafficking Around the World (4 page)

Read Human Trafficking Around the World Online

Authors: Stephanie Hepburn

Tags: #LAW026000, #Law/Criminal Law, #POL011000, #Political Science/International Relations/General

In August 2005 the traffickers brought the victims to the United States with temporary H-2A visas. Upon arrival, armed guards confiscated the victims’ return tickets, visas, and passports. The victims spent the first month primarily working on Howell Farms, Inc. in North Carolina before they were taken to perform demolition on Katrina-ravaged buildings in New Orleans (Asanok et al., 2007). “One indicia of trafficking is that the victims are moved from place to place, so that they are kept in disorientation,” Johnson said. “They were moved around within New Orleans; each place was worse than the previous. They were housed in the buildings that they were demolishing. The Capri Hotel was the final, and the worst, stop.” While in New Orleans, the victims were not paid and were closely supervised by an armed guard to ensure that they did not try to escape. The same guard charged the victims for purchasing their food, but without pay the workers began to go hungry (Asanok et al., 2007). As a result of pressure brought by the Thai embassy, the traffickers had to return the victims to North Carolina in order to meet with embassy representatives—who were beginning to question the victims’ whereabouts. “Unable to fit all of the victims into their vehicles, the traffickers left seven in New Orleans with a guard,” Johnson said. There were other victims related to this case, some of whom had arrived on a different and previous order. Their whereabouts remain unknown. Others were simply too fearful to participate in the legal proceedings again Million Express Manpower and disappeared before social service providers were able to gain their trust.

Johnson believes that the post-Katrina setting, in which normal community networks had been compromised and the population was in flux, created ideal trafficking conditions. Devastation from a natural disaster, Johnson says, creates a sudden high demand for low-wage and largely unskilled labor. Disruption of the traditional labor supply leaves room for illicit contractors to move in, and new workers can be brought in unnoticed. Additionally, law enforcement personnel are overextended and do not have the resources to monitor a trafficking scenario.

On September 5, 2005, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the U.S. Department of Labor temporarily suspended the enforcement of job safety and health standards in hurricane-impacted counties and parishes in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Affirmative-action requirements were also suspended. Within the next several days, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) suspended for 45 days the requirement that employers confirm employee eligibility and identity, and then-president Bush temporarily suspended the Davis-Bacon Act, lifting wage restrictions for nearly 2 months. Under the act, construction workers are guaranteed the prevailing local wage when paid with federal money (Donato & Hakimzadeh, 2009). These changes, intended to speed recovery in the disaster-ravaged region, also opened the floodgates for worker exploitation and human trafficking. For instance, the number of Department of Labor investigations in New Orleans dropped from 70 in the year prior to Katrina to 44 in the year after—a 37 percent decrease. “The Department of Labor is the federal cop on the workplace safety, wages, and hours beat,” Congressman Dennis Kucinich said. “Where was ‘Sheriff Labor’ during the early months of the reconstruction?” (U.S. House of Representatives, 2007, p. 2).

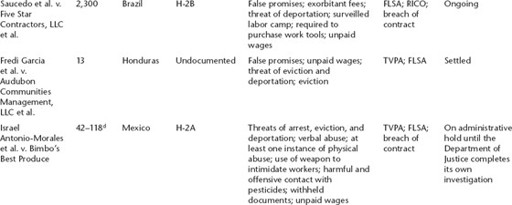

One of the groups most affected by the lack of regulation was guest-workers. There seems to be a general misperception that all migrant workers are in the United States illegally, but nearly all—98.3 percent—of persons identified as potential forced-labor victims in the Gulf Coast region were visa holders. (See Table 1.1.) Of those 3,663 persons, 72 were H-2A visa holders, 361 were H-1B visa holders, and 3,230 were H-2B visa holders (these are the lowest estimates of the potential victims in the alleged Gulf Coast cases).

5

U.S. companies or their agents recruited most of these workers. This is not uncommon practice. U.S. companies often use guestworker visas to recruit low-skilled foreign workers. In 2005 alone, employers brought in 121,000 guestworkers under the H-2 program (Bauer, 2007, p. 1; U.S. House of Representatives, 2008). What stands out in the data we collected are the high number of alleged trafficked persons in the Gulf Coast who were H-2B visa holders, who, as we have seen, are particularly vulnerable to employer exploitation and abuse.

5

U.S. companies or their agents recruited most of these workers. This is not uncommon practice. U.S. companies often use guestworker visas to recruit low-skilled foreign workers. In 2005 alone, employers brought in 121,000 guestworkers under the H-2 program (Bauer, 2007, p. 1; U.S. House of Representatives, 2008). What stands out in the data we collected are the high number of alleged trafficked persons in the Gulf Coast who were H-2B visa holders, who, as we have seen, are particularly vulnerable to employer exploitation and abuse.

In 2005, the year the Gulf Coast region was devastated by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, no government agency claimed ownership of the H-2B program. The Department of Labor stated they had little to no authority to act on behalf of H-2B visa holders. Although statutes existed to protect H-2A visa holders, there was no similar protection for nonagricultural guestworkers. The H-2A program grants workers free housing, access to legal services, employment for at least three-fourths of the total hours promised in his or her contract (this is called the “three-quarters guarantee”), compensation for medical costs and permanent injury, as well as various other benefits (U.S. House of Representatives, 2007). In contrast, wage protection provided to H-2B visa holders was skeletal at best. Employers utilizing the H-2B program were obligated to offer full-time employment that at minimum paid the prevailing wage rate, but because the H-2B visa was established via a 1994 Department of Labor administrative directive instead of through statutory regulation, the Department of Labor claimed to lack the legal authority to enforce its requirements (U.S. Department of Labor, 1994; U.S. House of Representatives, 2007).

Congress exacerbated the problem when in 2005 it vested the Department of Homeland Security with enforcement authority over the H-2B visa program. As a result, the Department of Labor had no authority to enforce the provisions and regulations of the program. According to Kucinich, the Department of Labor had the authority to grant or deny certification for a foreign labor contract through its Office of Foreign Labor Certification, but it could not deny certification for an employer who had been prosecuted for labor law violations. Instead, the Department of Homeland Security was granted complete authority over the enforcement of H-2B contract terms. Irrespective of the statutory limitations impeding the Department of Labor’s advocacy on behalf of H-2B workers, the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division still had the authority and the responsibility to prosecute employers for violations of the Federal Labor Standards Act and the Davis-Bacon Act (U.S. House of Representatives, 2007).

TABLE 1.1

Alleged Gulf Coast Forced-Labor Trafficking Cases

a

Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000.

Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000.

b

Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (1970).

Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (1970).

c

Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

d

Thirty-seven persons were brought from Mexico to work at Bimbo’s in 2005/2006, approximately 39 in 2006/2007, and approximately 42 in 2007/2008. It is unknowr how many of the workers came back annually.

Thirty-seven persons were brought from Mexico to work at Bimbo’s in 2005/2006, approximately 39 in 2006/2007, and approximately 42 in 2007/2008. It is unknowr how many of the workers came back annually.

e

U.S. Department of State, 2009c.

U.S. Department of State, 2009c.

Sources:

Interviews and correspondence with Mary Bauer, Lori Johnson, Jacob Horwitz, Dan Werner, Stacie Jonas, Robert Anthony Alvarez, and Dan McNeil.

Interviews and correspondence with Mary Bauer, Lori Johnson, Jacob Horwitz, Dan Werner, Stacie Jonas, Robert Anthony Alvarez, and Dan McNeil.

Fortunately, in late 2008, discussions between the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Labor resulted in an agreement that the Department of Labor should be delegated H-2B enforcement authority. Numerous amendments to the Department of Labor regulations updated the procedures for issuing labor certification to employers sponsoring H-2B guestworkers (U.S. Department of Labor, 2008, 2009b). The amendments, unlike the 1994 administrative directive, expressly prohibit employers from passing onto foreign workers the cost of attorney or agent fees, the H-2B application, or recruitment associated with obtaining labor certification. The Federal Register Rules and Regulations state that these are business expenses associated with aiding the employer to complete the labor certification application and labor market test: “The employer’s responsibility to pay these costs exists separate and apart from any benefit that may accrue to the foreign worker” (U.S. Department of Labor, 2008, p. 78,039).

TRAFFICKING WITHIN THE UNITED STATES

Sex trafficking is the most common form of human trafficking identified among U.S. citizens. Although HHS identified more than 1,000 internal trafficking victims in 2009, it is extremely difficult to know how many persons this form of trafficking actually affects (U.S. Department of State, 2010). This uncertainty reflects both the hidden nature of the crime and the emphasis studies have placed on international as opposed to internal trafficking. There are estimates on the sexual exploitation of minors within the United States, but there is little information on children and adults trafficked within the United States for forced labor or commercial sexual exploitation (Estes & Weiner, 2002, p. 5; Clawson et al., 2009, p. 4).

Richard J. Estes and Neil Alan Weiner in the report

The Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in the U.S., Canada and Mexico

estimate that as of 2001 there were between 244,000 and 325,000 U.S. youths at risk (Estes & Weiner, 2002, p. 150). These numbers may have drastically changed since the release of this report.

The Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children in the U.S., Canada and Mexico

estimate that as of 2001 there were between 244,000 and 325,000 U.S. youths at risk (Estes & Weiner, 2002, p. 150). These numbers may have drastically changed since the release of this report.

The Child Labor Coalition estimates that 5.5 million U.S. youths between ages 12 and 17 are employed. This number does not include illegal employment such as the use of U.S. children in sweatshops (Clawson et al., 2009, p. 6). In 2008 the Department of Labor found 4,734 minors illegally employed. Forty-one percent of cited child labor violations included children working under hazardous conditions, in hazardous environments, and/or using prohibited equipment. Other child labor violations involved children under the age of 16 working too late, too early, or for too many hours (U.S. Department of Labor, 2009a). Grocery stores, shopping malls, restaurants, and theaters, where children are often employed, have historically shown a high level of noncompliance with child labor laws. Children in agricultural employment are also a particularly vulnerable population. In 2009 the Wage and Hour Division cited five agricultural employers for employing children under the legal age of employment to perform labor in North Carolina blueberry fields (U.S. Department of Labor, 2009a). The Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs estimates that hundreds of thousands of U.S. children, some as young as nine years old, are migrant and seasonal farmworkers (Hess, 2007, pp. 2, 6, 11).

There is a common misconception among Americans that human trafficking within the United States is an underground industry whose victims and abusers are exclusively immigrants. The story of one 15-year-old illustrates that U.S. citizens and legal residents can also become victims of human trafficking. In September 2005 “Sarah” ran away from home and met her traffickers, Matthew Gray (30 years old) and Jannelle Butler (21 years old), through a friend. They took Sarah to an apartment in the Washington Park area of Phoenix, where they bound and gang-raped her.

6

The traffickers then forced Sarah into a dog kennel and with a gun threatened to harm her and her family. When fearful of police, the traffickers hid Sarah in a hollowed-out box spring. The traffickers forced Sarah to prostitute for 42 days. One of her captors, Gray, raped Sarah throughout her time in captivity (Villa & Collom, 2005a; Park, 2008).

6

The traffickers then forced Sarah into a dog kennel and with a gun threatened to harm her and her family. When fearful of police, the traffickers hid Sarah in a hollowed-out box spring. The traffickers forced Sarah to prostitute for 42 days. One of her captors, Gray, raped Sarah throughout her time in captivity (Villa & Collom, 2005a; Park, 2008).

In early November Sarah managed to call her mother from Gray’s cell phone. Sarah was too scared to give her mother details regarding her captors or on her exact location for fear that they would harm her family. This fear was not unfounded, as Gray knew where her mother and family members lived. Arizona policeman Greg Scheffer says victims often don’t call the police, even when given an opportunity to do so, for fear of reprisals (Villa & Collom, 2005b).

After receiving her daughter’s phone call, Sarah’s mother called the police. The officers made repeat visits to the apartment where Sarah was held and were, at times, just inches away. After Butler was arrested on the last visit and placed in the patrol car, she informed police that Sarah was hidden in the box spring. Butler expressed concern that Sarah might run out of oxygen as she almost fainted the last time she was forced to hide in the compartment. Interestingly, Butler was a victim of similar crimes at age 17. It seems that she subjected Sarah to the same strategy of beatings, threats, and imprisonment that she experienced. Phoenix police sergeant Chris Bray told the

Arizona Republic

that Butler’s actions are not uncommon in victims of abuse, specifically child abuse. “It’s kind of a battered-child syndrome,” Bray said. “It happened to them. They hated it. And then they do it to someone else” (Villa & Collom, 2005b).

Arizona Republic

that Butler’s actions are not uncommon in victims of abuse, specifically child abuse. “It’s kind of a battered-child syndrome,” Bray said. “It happened to them. They hated it. And then they do it to someone else” (Villa & Collom, 2005b).

Other books

Sacremon (Harmony War Series Book 1) by Michael Chatfield

Paranoid Park by Blake Nelson

Third Eye Watch (A Serena Shaw Mystery) by Nipa Shah

Corridors of the Night by Anne Perry

The Seduction - Art Bourgeau by Art Bourgeau

Cedar Woman by Debra Shiveley Welch

Play Dead by David Rosenfelt

Fatal Destiny by Marie Force

Little Amish Matchmaker by Linda Byler

Deadline by John Dunning