I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class (23 page)

Read I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class Online

Authors: Josh Lieb

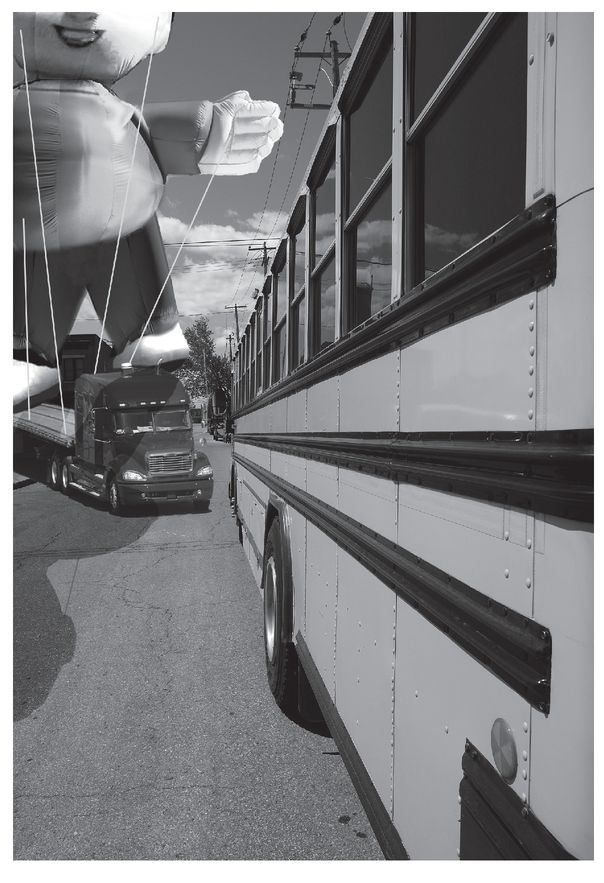

PLATE 17: An enormous, inflated, hot-air balloon.

Maybe forty feet tall. Fully worthy of being floated down

Broadway during the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Maybe forty feet tall. Fully worthy of being floated down

Broadway during the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Tatiana, my sweet. Forgive me. I underestimated you.

She sits in the center of the Buick’s front seat, the only one in the car not screaming like a spasmodic banshee. She is calm. Placid. The eye of the storm. Her face is wreathed in a smile so sinister and satisfied that she looks like she just swallowed Big Bird.

She winks at me.

And that’s when the

really

bad news hits me.

really

bad news hits me.

My network is in a state of

High Alert. Code Red. Triple Security

. All my operatives are under strict orders to

react with extreme prejudice

. Any anomaly is to be treated as a threat until it’s proved otherwise.

High Alert. Code Red. Triple Security

. All my operatives are under strict orders to

react with extreme prejudice

. Any anomaly is to be treated as a threat until it’s proved otherwise.

The balloon is only fifty yards away now, coming closer. . . .

And the whole world goes into slow motion.

Forty-five . . .

“No,” I whisper.

Around me, my classmates wave and scream and hop like savages dancing to please their god of destruction.

It’s forty yards from the bus now . . . thirty-five. . . .

“No . . .”

Its enormous left foot bounces against the side of a truck, then snags on a small tree and rips it from the ground.

“No,” I order. “Don’t fire. Stand

down

.”

down

.”

Thirty . . . twenty-five . . .

Stephen Turnipseed is pounding me on the back and laughing. Big drops of spittle spray from his mouth and splatter across my cheeks, my nose, my eyes.

“Don’t fire. . . . Please . . .”

It runs into an overhead power line and snaps it.

Twenty . . .

The broken power cables writhe like snakes with rabies, sending electrical sparks arcing high into the air.

“

Listen

to me!”

Listen

to me!”

Fifteen . . .

“No!” I scream, not caring who hears me. “No! Don’t fire! Stand down!

Stand down!

”

Stand down!

”

Maybe the pilot can’t hear me over the din of the shrieking animals around me. Maybe he can’t understand what I’m saying. Maybe he can hear me, but he’s too freaked out by the approaching floating colossus to pay any attention to my words.

Ten . . .

All I know is I’m still screaming, “Stand down! Stand down!” when the NewsChannel 5 traffic copter fires an AIM-92 stinger missile right at the heart of the Oliver Watson balloon.

Chapter 37:

REVENGE OF AFTERMATH!

Mom is crying in the school parking lot. Liz and Logan are next to her, hugging each other and whimpering. They’d be crying, too, but I think they’re all out of tears by now.

Again, only Tati is calm. She sits serenely on the hood of Mom’s car, snickering to herself. She catches me watching her and winks at me again.

No one on the bus can believe they actually saw a lightning bolt strike the balloon out of a clear blue sky. Especially because no one actually saw that. But that’s the story I’m having my operatives spread, and since it’s the only plausible explanation, the police are buying it.

“Just a giant lightning flash, right out of nowhere,” says the pilot of the NewsChannel 5 traffic copter.

“Big flash of electricity,” says Tippy the bus driver, who I suddenly realize looks a lot like that nephew The Motivator asked me to give a job to two years ago.

“It was scary! A huge, jagged thunderbolt! I saw the whole thing,” says Pammy Quattlebaum, who was five miles away when it happened.

Such is the power of persuasion that even the people who saw the missile—who

know

they saw a missile—are starting to believe they saw lightning strike.

know

they saw a missile—are starting to believe they saw lightning strike.

“Biggest bolt of lightning I ever saw,” says Stephen Turnipseed. And he gets into a fight with Cory Carter when Cory says he saw a rocket.

114

114

Everyone is being very sympathetic toward me. Especially Agents Jablon and Silveri, who were at the airport about to head back to Washington when news of the balloon downing broke. They appear to believe the cover story, but with such a strange incident coming right on the heels of the Sheldrake assault, they decide to stay in town for a few more days.

“A ginormous spaghetti of light came out of the sky!” I tell the agents.

“You already said that,” says Agent Jablon.

“Shut up, Joe,” says Agent Silveri.

Principal Pinckney nearly fainted when he saw them drive up. Which is probably why he decided to hold today’s student council elections as planned, in the interest of saying, “Nothing to look at here. Just business as usual. No reason for the FBI to hang around this school.”

I would tell him how suspicious that looks, but I don’t want him to have a stroke.

I lick my palms and smear some saliva under my eyes so Mom will think I’ve been crying, too. Perversely, that seems to cheer her up a little. It’s important to her that I care about the balloon.

“Oh, Ollie,” she moans, as she crushes me to her bosom. “It was our big surprise! We worked

so hard!

”

so hard!

”

“It was supposed to win you the stupid election,” says Liz, who is kicking the tires of Mom’s car. I’ve never seen Liz look this sad before. I didn’t know she was capable of emotion this deep.

“I’ll still win,” I say, and Liz smiles a little. Maybe I won’t die after all.

“But that was such a funny lightning bolt,” says Mom. “I never saw a lightning bolt that was black before.”

“With fins,” says Logan.

“Yeah,” says Tati. “That was one

craaaazy

lightning bolt.” She holds her sides to keep from breaking a rib while she laughs.

craaaazy

lightning bolt.” She holds her sides to keep from breaking a rib while she laughs.

She was the one who worried me, in the aftermath. I didn’t know what she would say to the FBI when they interviewed her. She was certainly close enough to know it wasn’t a lightning bolt that ruined my surprise, and, unlike the others, she’s too hardheaded to be convinced otherwise.

I shouldn’t have worried. I’d forgotten about her compulsive hatred for authority figures.

Agent Silveri said to her, “Tell me what you saw, little girl.”

And she said, “Go climb a tree, G-Man.”

So then he said, “What’s your name?”

And she said, “Your mother.”

He gave up after that. I suspect she does know it was a missile. And I suspect she doesn’t care. I think she

likes

a world that’s dark and dangerous and doesn’t make any sense. It’s like she was raised by vampires.

likes

a world that’s dark and dangerous and doesn’t make any sense. It’s like she was raised by vampires.

Right now Mom is shooting Tati a dirty look. “How can you be laughing? We worked so hard, and now it’s all for nothing!”

Time for Tubby to save the day.

I push myself away from Mom so she can see the rapturous smile I’ve constructed on my face. I want her to know I’m happy. “It was the bestest fireworks I ever saw,” I exclaim. “Better than the Fourth of July!”

And now “Mom” is happy, too, and hugging me again. “Oh, Sugarplum,” she says. “You make everything beautiful!”

“You tell ’em, Sugarplump!” shouts Tati.

“You’re the best Sugarplum ever,” says Liz, who is suddenly hugging me, too, from behind. Now Logan has squeezed in to hug me, too—tough to do for such a large girl. Somehow they’re all crying again.

If I ever manage to breathe, I just might get a chance to give my speech.

Chapter 38:

THE MOMENT YOU’VE ALL BEEN WAITING FOR

And here we are. A school auditorium, throbbing with the voices of a thousand students saving each other seats, tripping over each other’s feet, sharing pieces of bubble gum they keep expertly hidden from the eyes of teachers.

And here I am, sitting onstage next to Randy Sparks (again), who’s wearing a new blue blazer that actually looks kind of sharp. He’s smiling like he’s relaxed—Verna must’ve taught him that—but I notice he has to hold his knees together to keep them from knocking. He turns to me and whispers, “I’m nervous, Ollie.”

“Please don’t hit me, Randy,” I reply. “Not in front of everybody. Do it when we’re alone. It’s too embarrassing.”

I figure it can’t hurt to confuse him one last time, just before he speaks.

But it doesn’t work. He opens his mouth to protest, then shuts it. He nods, almost wisely. It’s like he’s learning something about me (or himself) while I watch him. He turns away from me and studies his speech.

There’s Tatiana, in the fifth row, writing dirty words on Logan’s arm.

There’s Megan Polanski, the ex-Most Popular Girl in School, staring daggers at her ex-best friends Shiri O’Doul and Rashida Grant, who are busy ignoring her. They decided yesterday that she “wasn’t cool.” Rashida’s the new Most Popular Girl in School. We’ll see how long she lasts.

There’s Josh Marcil, his fleshy freckled fingers smeared with chocolate, telling anyone who’ll listen that he found a toilet that’s full of malted milk balls. He must’ve crawled through the gap under the door.

There’s Jack Chapman, a few seats over, who should, by all rights, be sitting up here in my place. No matter who gets elected today, he’ll always be Jack Chapman. If anything, he’s become more impressive and all-American since he pulled out of the race. His shoulders seem wider, his eyes seem clearer—he seems to have grown up overnight. The only weird thing is the handkerchief he carries these days, and the way he’s always blowing his nose. Well, every great man has his eccentricities.

There’s Alan Pitt, whose acne had been clearing up until he called me “Sir Eats-a-Lot” three days ago.

115

Now he scratches miserably at his face, which looks like he’s been making out with a slice of pizza.

115

Now he scratches miserably at his face, which looks like he’s been making out with a slice of pizza.

I don’t see Mom, though I know she’s here, somewhere, to witness my moment of triumph. But there’s Moorhead, patting the seat next to him, which he’s saved for

La Sokolova

. She smiles at him from the aisle and pushes her way past Lanny Monkson (who is legally blind) to get to the proffered seat.

La Sokolova

. She smiles at him from the aisle and pushes her way past Lanny Monkson (who is legally blind) to get to the proffered seat.

Agents Jablon and Silveri stand in the back of the room, glowering importantly. A few feet from me, Mr. Pinckney sweats at the podium, looking like he picked the wrong time to take an extra-strength laxative. “Thank you all for coming,” he says, “to what I think is the most important day on the school calendar. . . .”

I tune him out by turning up the sound on my earbud. It’s playing my new favorite song, Captain Beefheart’s “Yellow Brick Road.” I am wearing my favorite jeans and my lucky striped shirt, the shirt I wore when I fixed the Kentucky Derby.

116

116

And so the speeches begin. The rising seventh graders start, from lowest offices to highest. Those ambitious souls who want desperately to be seventh-grade treasurer (even though the seventh grade has no money) stutter out their nervous little paragraphs and scurry back to their chairs. The audience pretends to be interested at first, but they soon look like they all wish they had earbuds of their own.

Sheldrake’s voice interrupts the song. “Sorry to intrude like this, Oliver, but I wanted to wish you good luck. Though I’m sure you don’t need any. I know this is important to you, and even if I don’t quite understand why, I’m glad you’re getting what you want.”

“I also want to tell you how grateful I am.” I scowl impo tently—he knows I can’t tell him to shut up. “I’m almost ready to come down now, and I really want to thank you for giving me this opportunity to get my head together.”

Get my head together

—that’s Daddy language. I’ll have to give Lionel a stern talking-to when he lands. There will be no hippie talk in my organization.

—that’s Daddy language. I’ll have to give Lionel a stern talking-to when he lands. There will be no hippie talk in my organization.

“Anyway, break a leg and all that. I’m rooting for you from up here.” And the Captain resumes playing.

The rising seventh graders finish their turn, and Penny Trimble is at the lectern now, giving her pitch for why she should be eighth-grade class secretary. I tune down the earbud to hear what she’s saying. “. . . and, if elected, I promise to put pop

117

in the water fountains. . . .” She laughs lamely. The audience laughs not at all, which leads me to suspect she’s not the first person to make that particular ancient joke today.

117

in the water fountains. . . .” She laughs lamely. The audience laughs not at all, which leads me to suspect she’s not the first person to make that particular ancient joke today.

Other books

The Wedding Favor by Caroline Mickelson

A Stranger Came Ashore by Mollie Hunter

Alice Next Door by Judi Curtin

Death by Cashmere by Sally Goldenbaum

Oz - A Short Story by Ann Warner

Irresistible Impulse by Robert K. Tanenbaum

Silencer by Campbell Armstrong

To Kill a President by By Marc james

Evidence of Desire: Hero Series 3 by Monique Lamont, Yvette Hines

His Surprise Son by Wendy Warren