I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class (4 page)

Read I am a Genius of Unspeakable Evil and I Want to be Your Class Online

Authors: Josh Lieb

I turned this money into a certified check, which I used to start an online stock-trading account. The rest is history. Unfortunately, after I made my first million, certain people got curious—the Internal Revenue Service, specifically. I knew I needed some cover.

So I went looking for some.

My second-grade teacher Mrs. Guerra used to joke that I was so stupid I could get lost on my way back from the bathroom.

22

In reality, the reason I used to wander away from school so often was that I was looking for cover. I found it, strangely enough, outside the same church basement where I’d won my bingo money. An Alcoholics Anonymous meeting was letting out, and the lost souls were congregating on the sidewalk. One of them caught my attention immediately.

22

In reality, the reason I used to wander away from school so often was that I was looking for cover. I found it, strangely enough, outside the same church basement where I’d won my bingo money. An Alcoholics Anonymous meeting was letting out, and the lost souls were congregating on the sidewalk. One of them caught my attention immediately.

AA is a great resource for finding cover agents. Many of these creatures come from impressive backgrounds and have done great things in the past—but they’ve all been humbled by their addiction to booze. Once they’re clean, they are frequently desperate to redeem themselves in the eyes of the world.

When I first saw Lionel Sheldrake, he had been sober for ninety-three days and smelled like an overcooked lamb chop (

see plate 5

). I was immediately impressed by his bone structure and trim figure—he would clean up well. His clothing was old but of good quality; Brooks Brothers, from the look of it. So I climbed out of the garbage can I was spying on him from and asked the nice man if he would help a lost little boy find his was back to school. The nice man said yes.

see plate 5

). I was immediately impressed by his bone structure and trim figure—he would clean up well. His clothing was old but of good quality; Brooks Brothers, from the look of it. So I climbed out of the garbage can I was spying on him from and asked the nice man if he would help a lost little boy find his was back to school. The nice man said yes.

During our walk, I asked him a lot of stupid questions, like children do, and quickly learned his name; it had a nice patrician ring. And I liked his accent—he spoke with the clipped vowels you hear in the New England prep school elite. I decided I’d found my man. As he said goodbye to me on the school steps, I slipped five thousand dollars into his hand. “Get yourself a new suit and a haircut,” I told him, “and meet me outside the church at noon tomorrow.” He blinked, then stared at the money with wide, frightened eyes—he acted as if a butterfly had just crapped an emerald into his hand. I reached out my pudgy little paw and curled his fingers around the cash: “There’s plenty more where that came from.”

23

Then I walked into school.

23

Then I walked into school.

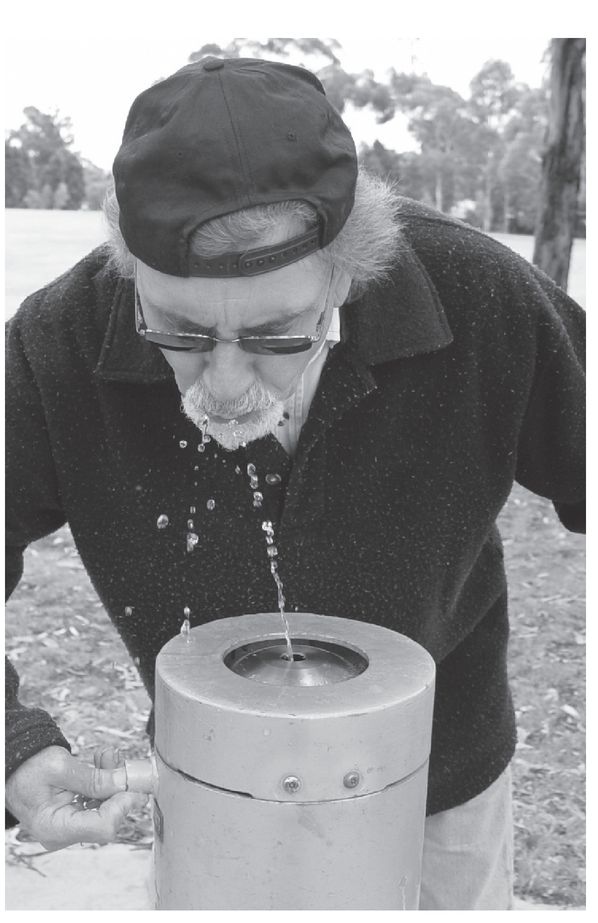

PLATE 5: When I first saw Lionel Sheldrake,

he had been sober for ninety-three days and

smelled like an overcooked lamb chop.

he had been sober for ninety-three days and

smelled like an overcooked lamb chop.

He was an hour late the next day, and when he did show up, he was drunk. I couldn’t really blame him for that. Seven-year-olds who hand out five-thousand-dollar tips are unusual. He told me later that I’d spooked him so badly, he’d sworn not to come back, but curiosity and greed had gotten the better of him. I was glad. A little research on the Internet had taught me that Lionel Sheldrake, recovering alcoholic with an apartment on skid row, used to be Lionel Sheldrake, hotshot insurance executive with a house in Happy Hollow. Then he’d started drinking and lost it all. He was a native of a good Connecticut suburb and a graduate of Cornell University. His ancestors came over on the

Mayflower

—all that junk that looks good in the newspaper. I’d chosen well.

Mayflower

—all that junk that looks good in the newspaper. I’d chosen well.

I got him a haircut. I bought him a suit. I made him sign a few contracts. And before long, people were saying that Lionel Sheldrake was an

important

24

man.

important

24

man.

Actually, he’s a whiny man, and I’m getting tired of his excuses. “Beefheart,” I bark, as Sheldrake prattles on. Somewhere in the depths of the control center, one of my minions hears me and obeys my command. The sweet dis cordant notes of my favorite song, “Adaptor,” by Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band immediately fill the room at an ear-shattering volume, drowning out Sheldrake completely. My face relaxes into a smile. Nobody understands me like the Captain.

And then I frown. Because an automated warning voice has risen over the music. In flat, robotic tones, it repeats, over and over again: “Daddy’s home. Daddy’s home. Daddy’s home.”

Chapter 5:

MY DOG LOLLIPOP

According to the fortune-cookie logic most people live by, the best things in life are free. That’s crap. I have a gold-plated robot that scratches the exact part of my back where my hands can’t reach, and it certainly wasn’t free.

But the best things in life

can

be cheap. My dog Lollipop cost only fifty-three dollars in adoption fees at the animal shelter. I found her there when she was three months old. She was a pudgy dewdrop of brindled fur and baby teeth, smiling happily at the world from a cold and barren cage. Her tail flicked back and forth like a windshield wiper through a puddle of her own pee. Apparently, she had to be kept apart from the other dogs because they picked on her. Idiots.

can

be cheap. My dog Lollipop cost only fifty-three dollars in adoption fees at the animal shelter. I found her there when she was three months old. She was a pudgy dewdrop of brindled fur and baby teeth, smiling happily at the world from a cold and barren cage. Her tail flicked back and forth like a windshield wiper through a puddle of her own pee. Apparently, she had to be kept apart from the other dogs because they picked on her. Idiots.

Daddy didn’t like her, either. He kept trying to steer me to something “cuter.” But I knew she was my dog the second she lunged at the bars of her cage and tried to bite his stupid face off.

When my dog Lollipop was five months old, she ran away. I don’t think Daddy was sorry to see her go. Lolli had all these precious habits, like chewing up his man-sandals and peeing on his briefcase. One time, she made a poo on his favorite chair that looked almost exactly like a little brown dog. She’s a very talented girl!

Mom tried to cheer me up by making me an ice-cream sundae every night. Actually, I was only pretending to be sad.

25

Lolli hadn’t really run away. I’d sent her to a secret dog-training facility in the Basque region of Spain.

25

Lolli hadn’t really run away. I’d sent her to a secret dog-training facility in the Basque region of Spain.

The Basque are an ancient people famous for wearing little hats and drinking wine in great curving spouts from leather canteens (

see plate 6

). They provide local color in the works of Ernest Hemingway. Since time began, apparently, they have lived in what is now southwest France and northern Spain.

see plate 6

). They provide local color in the works of Ernest Hemingway. Since time began, apparently, they have lived in what is now southwest France and northern Spain.

Generally, you trace the ancestry of a people by looking at their language. Even if we didn’t have history books to tell us, we’d know that Americans come from England, Africa, and everywhere else because the language we speak has words from England, Africa, and everywhere else.

We don’t know anything of the sort about the Basque. Their language is an absolute mystery, completely unrelated to the French and Spanish gabble around them. We don’t know where they came from, originally. Did their ancestors arrive in Basque country on ships from ancient Egypt? Did they travel overland from Finland? There’s just no telling.

PLATE 6: The Basque are an ancient people famous

for wearing little hats and drinking wine in great

curving spouts from leather canteens.

for wearing little hats and drinking wine in great

curving spouts from leather canteens.

A consequence of speaking such a strange language is that almost no one understands a word they’re saying.

Daddy was a little surprised to discover Lolli, perfectly healthy, sitting in our driveway one afternoon about two months after she ran away. He was even more surprised to discover she was now house-trained, could be walked without a leash, and fetched the newspaper every morning.

He would be outright blown away if he knew some of the other tricks she’d learned. Only I know about those, and only I know the Basque commands that make her do them:

Gelditu

= “Stay.”

= “Stay.”

Eseri

= “Sit.”

= “Sit.”

Hil

= “Kill.”

= “Kill.”

Hil Ito

= “Kill but make it look like an accidental drowning.”

= “Kill but make it look like an accidental drowning.”

That’s just a sample. She has over eighty commands in her vocabulary.

27

Naturally, everyone who hears me thinks I’m just speaking some childhood nonsense language to my dog. My only worry is if I run into a Basque speaker in Omaha. And that is not likely.

27

Naturally, everyone who hears me thinks I’m just speaking some childhood nonsense language to my dog. My only worry is if I run into a Basque speaker in Omaha. And that is not likely.

Lollipop is sitting at Daddy’s feet right now, staring up at him as he eats his dinner. She always sits there. Waiting. Not waiting for him to drop some food (he won’t). Waiting for something bigger. Like a cobra watching a zookeeper, waiting for him to look away for

just

a second. . . .

just

a second. . . .

Daddy tries to ignore her, but I notice he always keeps a firm grip on his knife.

He’s looking thoughtfully over his glasses as he cuts his ham steak into dainty bites and tells us about his amazing day.

“I told the man, ‘Look, I’m flattered—it’s a very generous offer. But it’s really not for me. I’m needed where I am.’” He lowers his eyes modestly. Daddy is constantly lowering his eyes modestly. It’s like he’s scared he’ll see all the people he thinks are admiring him.

“You did the right thing,” gushes Mom. She’s leaning forward on her elbows, eager not to miss a syllable. “You always do the right thing!” The poor dear really doesn’t know any better.

To my thinking, the only “right thing” my father ever did was marry Mom. That happened about six months after their first date, during their senior year at the University of Nebraska. I have a picture of them on that date (

see plate 7

)—it was a dance of some sort. Mom is the beaming blonde head-cheerleader. Daddy lurks next to her, a frazzled, bowtied nerd, who somehow mustered the nerve to ask this fertility goddess out and still can’t believe she said yes. So they got married, I was born a few months later,

28

and the end result is I have to eat dinner with this man every night. That’s at Mom’s insistence, by the way. Daddy and I would both prefer to eat in our rooms.

see plate 7

)—it was a dance of some sort. Mom is the beaming blonde head-cheerleader. Daddy lurks next to her, a frazzled, bowtied nerd, who somehow mustered the nerve to ask this fertility goddess out and still can’t believe she said yes. So they got married, I was born a few months later,

28

and the end result is I have to eat dinner with this man every night. That’s at Mom’s insistence, by the way. Daddy and I would both prefer to eat in our rooms.

PLATE 7: I have a picture of them

on that date—it was a dance of some sort.

on that date—it was a dance of some sort.

But I should let him finish his story: “So then he tried to offer me even

more

money, which kind of confirmed for me that my head was in the right place. I mean, I didn’t get into this business for the money.”

more

money, which kind of confirmed for me that my head was in the right place. I mean, I didn’t get into this business for the money.”

That’s for sure. Daddy runs the local public broadcasting affiliate. That’s the television channel that runs

Sesame Street

. Do you like

Sesame Street

? Well, Daddy doesn’t have anything to do with that. In fact, he thinks

Sesame Street

is “out of step with today’s pre-tweens.” But it’s popular, so he has to keep it on his station.

Sesame Street

. Do you like

Sesame Street

? Well, Daddy doesn’t have anything to do with that. In fact, he thinks

Sesame Street

is “out of step with today’s pre-tweens.” But it’s popular, so he has to keep it on his station.

Here’s what Daddy really does: Sometimes when you turn on a public broadcasting station, you will see an obese overrated opera singer singing and sweating (but mostly sweating). These performances are interrupted every seven minutes by a couple of people who smile too much. It’s usually a man with glasses and a woman whose teeth are too big for her mouth. Both of them look like they have very bad breath. Behind them, about twenty bored people sit at a table answering telephones.

Other books

Sound Of Gravel, The by Ruth Wariner

Ravens of Avalon by Paxson, Diana L., Bradley, Marion Zimmer

Neither Dead Nor Alive by Jack Hastie

The Recycled Citizen by Charlotte MacLeod

Lamplighter by D. M. Cornish

Darkness Falls by Keith R.A. DeCandido

Glorious Sunset by Ava Bleu

Wicked Appetite by Janet Evanovich

Dangerous (The Complete Erotic Romance Novel) by Ella Ardent