I Am China (3 page)

Authors: Xiaolu Guo

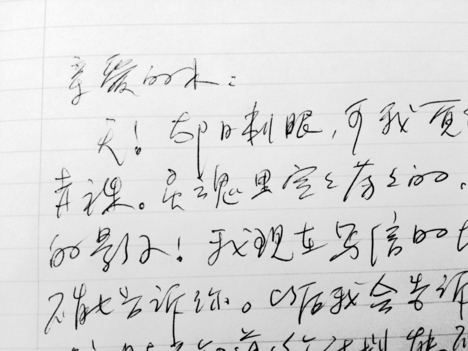

As the noise of morning from the street below surges up to her at the window, she shakes off her lethargy and the memory of the man’s touch only a few hours ago. Iona makes herself a strong cup of tea and sits down at her desk. On the table, beside a bulky English–Chinese Dictionary, sits a stack of photocopied Chinese documents. She leafs through the papers. Some appear to be letters; others are diary entries of hardly legible Chinese characters. She randomly picks one of the pages from the stack. Almost a scrawl, she thinks. This may be harder than I thought. She starts to read the first letter on the top of the pile.

Dearest Mu

,

The sun is piercing, old bastard sky. I am feeling empty and bare. Nothing is in my soul, apart from the image of you

.

I am writing to you from a place I cannot tell you about yet. Perhaps when I am safe I will be able to let you know where I am …

A few weeks earlier Iona had received an email from a publisher she hadn’t worked with before. They were interested in translating some Chinese letters and diaries—this motley heap on her desk. The pay wasn’t bad; most of the other translation jobs she took up were deeply boring: business or legal documents. Iona didn’t demand anything more: no information, no context. She remembered that lull after graduation where she seemed to live only moment to moment, with no plan, no future and five thousand Chinese characters lodged in her mind struggling to get out.

With long fine fingers she picks up a pencil and is ready to begin her work. But the pages look very confusing. Some pages don’t have dates on them, some are only half legible due to the deep black stain of the photocopier. The person who photocopied the original documents clearly didn’t speak Chinese as the pages are completely muddled and in no particular order. As she flicks through the folder, she begins to

wonder where the publisher got hold of them. It looks like some of the letters and diaries are from a long time ago, some more recent. They span nearly twenty years—there are dark spots from greasy fingers, smudges and ink stains and, in a few places, blurry characters as if someone had spilt something or cried onto the page. The editor at Applegate Books had sent her the heavy folder through the post with only a cursory note, saying the material related to a famous Chinese musician. “We need a bit of an idea of what we’ve got here,” she had written. “We think there could be something very interesting, but it’s hard to know without some sort of translation.” At a rare appearance at a publishing party recently, where she had stayed for two quick drinks and lingered mostly on the edges of the crowd—her skirt was too long, her conversation too intense—Iona had overheard this editor declaiming, “We used to publish eminent people’s biographies, like the Dalai Lama’s, but no one cares about ‘eminent figures’ any more. We’re more interested in marginal characters, especially if they’re connected to something big.”

There’s an officious-looking letterhead on the first letter. It reads “

Beijing 1540 Civil Crime Detention Centre

,” and there’s an address—somewhere she doesn’t recognise. She looks it up on Google maps. The pin lands in an empty grey landscape of main roads in the dark hinterland outside Beijing. She tries to imagine the desolation of a place like that—grey buildings, grey roads. She looks back at the messy script and starts to read.

11 November 2011

Dear Mu

,

I can’t bear this. My days are going by agonisingly slowly. There’s so little light from the window and I’m only accompanied by the stark and cold prison walls. How do I distract myself from going completely mad? I’m building the walls of our little flat inside the dark cave of this cell—our little home, where there is hot afternoon light and droopy plants, and we stand on our balcony facing the distant Xiang Mountain listening to those pirated foreign CDs we used to buy at the market—it soothes me when I think of all this

.

I know you cannot visit me, but I wish you would write to me. Your silence since I showed you my manifesto is just unbearable. How can you say you don’t believe in what I’ve written? Does it sound extreme to say that if you don’t believe in my manifesto, you don’t believe in me? Not to me it doesn’t, though you may laugh and call me naive, call me too idealistic. For me art, politics and love are all connected. You have seen how I lived for all these years—this is nothing new. It’s been nearly twenty years since I wrote my very first song, Mu! Twenty years is half a life! Half our lives, and all the time I’ve known you. And all that time you knew me. You lived with me. You accepted me by loving me. So what’s different now?

What manifesto? Iona wonders. She puts down her pencil and rereads what she’s translated. The voice on the page is angry. Even his handwriting is angry: the pen is pressed deep into the page; there are crossings-out and repetitions. And who is this Mu? Iona looks out of the window. The sky has whitened still further, as if it’s sucking all the energy out of the busying crowds below.

I’m going to say it again, even if you might not want to hear it. I know you, and I know you understand. There is no art without political commitment. All art is political expression. You know that—please, Mu, you know these things, why do you continue to block me out? We’ve talked about this. You knew I was going to distribute the statement at my concert. I felt stifled. We knew this might happen. Even as I miss you, I still think it was worth it

.

Imagine my arms around you in our bed. My woman, you know I love you

.

Your Peking Man

,

Jian

3

LINCOLNSHIRE, JANUARY 2012

The Chinese man sits at a table, holding a broken ballpoint pen. The surface of the table is heavily scratched, marked by the handwriting of every man who has sat there before him. Opening his diary, the pages all falling out, he tries to record the last few weeks. But he feels weary. Perhaps he is still jet-lagged, or disorientated. He stares at an oak tree outside the window whose twisted branches seem to stretch into the cloud laden sky like his thoughts. An old garden under an old sky. Old skin on an old body. Old, England is old, he murmurs to himself. His only reminder of China are two small cherry trees sheltering under the canopy of the huge oak. In this overheated room his eyes feel tired and his head congested. Maybe it’s the sleeping pills he’s been given to take. Or the words, words, words that the nurses fling at him in a language he can’t fully understand, despite what he learned at university. Their exasperated faces grimacing as he looks back at them blank and mournful.

He wonders about the unit he is in—the Florence Nightingale Unit—as he watches the strange people around him. All in matching striped pyjamas, either agonised or oblivious, but all hurting in some way. Why don’t they just call it what it is: “Mad People’s Reform Hospital,” exactly as the Chinese would do? He cannot understand the layers of confusion around him.

He looks back at the desk in front of him, his thoughts awash with recent events. The white-greyness around him is numbing. The humiliation, some days ago, when the doctor told him about his “borderline personality.” The words wouldn’t come. He felt totally inert and unable to argue back or explain what was really wrong.

Each night he stares at his battered guitar, which he brought all

the way from China; he has barely touched its metal strings since he got here. There’s a new dent on the body from the scuffle and fight at the concert. The rough hot hands which grabbed him and pulled him off the stage as the spotlights were burning his face. He hasn’t let that day into his thoughts for weeks. The guitar stands there, almost in judgement against him. But he can’t look at it without seeing the face of a Chinese girl, gazing up at him from the front of the crowd, her face open, full and light—the one still point in that underground den of mania.

Then he thinks of those rare days he tried to set aside and spend alone, away from his musician friends, trying to write a song in memory of his long-dead mother. He remembers he wept as a little child, in rage and utter confusion, standing before his mother’s gravestone. Now the days of being alone seem to be the normal pattern of his life.

Suddenly a shattering sound cuts through the air, like the frantic squawk of a bird trapped inside a room. Jian is startled out of sleep. He finds himself in the patients’ library. His fellow inmates are absorbed in Sudoku puzzles and blotted crossword grids. He’s awake, but tiredness clings to his limbs. His mind is possessed by hallucinatory impressions of his favourite “mala” beef-and-hog noodle soup with extra Sichuan peppers. The soup is steaming with heat right in front of his face. China is still alive for him. It has not been too long; he can still taste it. Smell the dank, sharp tang of the backstreets of Beijing and the tickle in his nose of the chilli in the air as he passes market stalls. He waits. His body dull and heavy.

It’s late evening. He looks up at the darkening sky, searching for familiar stars. He can see the Big Dipper, only a little obscured by clouds. Swathes of empty blank sky. And then he spots a comet, speeding fast towards the dark horizon. It zips along. Barely seen. As his eyes follow the trail of the comet’s burning dust, it feels like his body has been a comet zooming through the dark blue, from his birth in the leap year of 1972, when China was still in the throes of the Cultural

Revolution. There he was, landed in a half-Mongol, half-Beijing family. And now the comet has landed here, in some backwater of a sodden suburb of a second-rate town in a country long since descended from glory. It must have been something about his origins, he thinks, in the Year of the Rat, that has led him here, along an inscrutable path. The rat was running as he burst out of his mother’s womb. According to his grandparents, when he came out, a screaming brat in Beijing’s No. 8 Women’s Hospital, with the umbilical cord almost strangling his cries, his family was in the midst of Mao’s madness, the Chairman’s very last ideological war against the bogeyman of imperialism and the bourgeois infection of the people’s revolution. The rat was hissing, for sure, when his grandmother took him to an old palm-reader in Beijing’s Heavenly Gate Park. The white-bearded man opened the child’s palm, studied it for a few seconds, then announced: “There are dark clouds floating in his destiny; but his energy is stronger than the clouds. He will prevail if he avoids his wilfulness.” Jian’s grandmother didn’t fully understand those words as the child’s hand escaped from her grip and tried to flee from the palm-reader into the steamy Beijing streets. But the rat-child grew up in a time of indoctrination. He was fed on the milk of ideology: Marxism plus Leninism, interpreted through Maoism. And when he was eight he was spouting the slogans of the party, a robust, fierce, cherry-faced child, on a flag-hung stage, with a wooden gun and a red kerchief around his neck, as if bursting from a socialist-realist canvas. But his allegiance didn’t last long: his teenage years blew his spirit to the opposite shore.

Now, in the cool night, beneath a low English sky and distant Midland traffic, Jian’s past seems to him like dying embers, like a theatre of bright shadows playing quietly in his mind. A nurse passes, muttering words in a still-unfamiliar tongue; he remembers where he is. It is late, ten thirty at night. Slowly, he walks back to the bedroom he shares with other patients. He swallows a sleeping pill left for him in a small plastic cup on his bedside table. He sits on his bed, picks up his battered guitar and strokes the fretboard. The guitar has a line

of characters written on its side. Although it is very scratched, Jian can still read it:

—This Machine Kills Capitalists