I Am China (42 page)

Authors: Xiaolu Guo

“Make yourself comfortable. Do you want some soup? And I couldn’t resist getting some fish, too,” Jonathan says. “I remember you saying you liked sea bass.”

He seems to be in a good mood and glad that she’s there. He does not know why she is suddenly here for an urgent Saturday visit, but equally he does not ask, and she is glad of that. Iona feels nervous and unsettled. For a brief moment she thinks perhaps she won’t tell him anything. They can have a nice lunch together, perhaps go upstairs to bed, or sit and talk about books. She doesn’t know where to start, to ask about where his family is, or to tell him she has just been to Crete, and found Kublai Jian’s dead body in the basement of a police station with a suicide letter.

But there he is: Jonathan, a man whose life is about constructing

stories; the man who has sent her on a heavy emotional journey in the last few months. He is not at all just someone; he is a particular one, with a clear mind and firm presence.

“Where is your … family?” asks Iona hesitantly.

He turns his head from the stove and the hot steam rising from the pot of soup. He looks at her intently then turns back to his cooking. “They don’t live here any more. Let me get the cooking done and then we can talk.”

She stands behind him, watching him cooking, and waits. But she is not watching him at all, in fact her eyes see nothing of this reality. All she can see is a frozen body on a slab in the basement of Crete West Coast Police Station.

“Kublai Jian is dead,” she blurts out.

“What?”

“He died three days ago. I went to Crete, and I went to the local police station on the island to see the body.”

“You went to Crete? You saw his body? What? Stop, hang on. Iona, what are you talking about?”

“I just got back last night.” Iona’s voice is taut, frustrated. “I was too late … if I’d only gone to look for him two days earlier, or even a week earlier, a month earlier … I could have talked to him. I could have saved him! I knew he was in Crete. I figured out from his diary that Crete might be where he would go if he—if he felt that awful he—but I didn’t get there on time! I was too late! It’s so stupid of me!”

Iona’s control crumbles and she bursts out a flood of words and tears all at once. She feels extremely angry with herself.

Jonathan still doesn’t say anything. He stirs the soup very slowly.

Iona takes a battered piece of paper out of her pocket. Jian’s final letter to the world, a photocopy she brought back from Crete West Coast Police Station.

An hour passes. A deep sense of lassitude and loss have taken over them both, making them numb and speechless.

13

LONDON, NOVEMBER 2013

They sit down to eat the soup, barely lukewarm now. Green lentil soup and steamed sea bass to follow. Jonathan puts a bottle of white wine in front of Iona, while he opens a can of beer for himself. He breaks the silence.

“You were asking about my family before, well, I can tell you now … if you still want to know.”

Iona nods her head.

“A year ago, my wife took my two boys to India,” he starts slowly. “It was supposed to be a holiday, but then it stretched into months; later she returned with the boys but only stayed in London for two months. Then she went to India again, taking the children with her. She hasn’t been back since.”

“What about the children?”

“She’s put them in an international school in Delhi and is asking for a divorce.”

A pause. Iona puts down her spoon.

“And I can do nothing in India, apart from be a tourist. I need to be here with my work, and my company.”

“I’m sorry to hear that …” Iona says in a low voice. “You did mention you were in India a while ago.”

“Yes, and it turned out to be a disaster.” He finishes his soup, pushes his bowl to one side, and continues talking, his voice a little subdued. “She didn’t let on that she had been in love with her yoga teacher for the last two years. The holiday was a ruse; he’d moved out there and she couldn’t resist following. You could say I had a bit of a rude awakening. When I arrived in Delhi I was standing in the doorway with my suitcase still in my hands when suddenly her boyfriend came out

of her bedroom and started playing with my children in their sitting room like a big happy family.”

Jonathan falls silent. Iona watches him picking out bones from his sea bass with a fork.

“Is he Indian?” Iona asks.

“No, he’s a hippy from America, actually. Used to teach here, then moved to Delhi.” Jonathan’s voice becomes calmer. “I left and checked into a hotel. It was a new place, run by a Dutch couple. I holed up in the bedroom, put the air conditioning on, and read most of your translation. I thought: here I am, in a tacky Indian hotel, reading an exiled Chinese man’s story, unable to see my wife and my children. How absurd is that.” He sounds resigned, calm almost.

Iona takes a bite of the fish, it’s overcooked and cooling fast. She puts her knife and fork down, gazes into the dull eye of the fish on her plate, trying to comb out a tangle of thoughts. “Sorry, Jonathan, I don’t know what to say,” she mumbles.

“That’s OK. It’s mainly my fault, I realise …” Jonathan’s voice becomes clearer as he finishes his beer. “Her dissatisfaction with me is understandable. I care too much about my work, never give enough attention to her and the children. Right now I feel like I care more about Kublai Jian’s family than my own.”

It is a chilly Saturday afternoon. The winter air penetrates the door and streaks of condensation slip down the windowpanes. Iona looks out to the garden, the branches of the apple tree shiver and bend in the wind. But there is something unusual in today’s air. She looks more closely. Yes, it is snowing. Jonathan follows her eyes and watches the snow for a beat. They walk out of the kitchen, and stand in the middle of the garden, gazing at the gently falling flakes.

Iona reaches out her hand to the snow. Suddenly she no longer feels anxious, either with herself or with Jonathan.

They return inside and pick over the remainder of their lunch.

“I had a dream last night,” Iona says, looking at her food, and then

looks up. “It was horrible. I dreamed two Chinese policemen entered my flat and confiscated all the documents and my computer. Then I woke up. I wondered why I wanted to come here today—just to tell you Kublai Jian is dead, or something more? And then I found the answer on the way to your house.” Iona looks into Jonathan’s eyes. “You must publish this book, Jonathan, as soon as you can. I don’t think we should worry about pressure from China.”

Jonathan folds his arms, sits back and listens to her attentively.

“This is Britain after all!” Iona raises her voice, flicks her hair back dramatically. “It’s also my book, Jonathan. I’ve been working on this for months now. It’s got into me. You might not know what it is to struggle to translate and bring out something from another world into our world. It’s hard, and it takes it out of you, your energy, your days and nights. I’ve been getting deeper and deeper into these two people and their story. They’ve laid it all before me, like they’re ready to open themselves up to the world. And I have been a part of that opening up.”

Jonathan looks confused.

“Opening up—to China. Mu and Jian have such an incredible and tough story. It cuts across so much of what we take for granted. Don’t pretend you don’t understand. Don’t pretend you don’t believe in this too, Jonathan … And maybe it’s about responsibility also. It’s a cliché, but we owe it to them to tell their story, to show their love, and their destruction too …” Iona’s eyes glitter. “Maybe also to report on Jian’s death. We can show what his choice was and how he decided to die, and that’s important. I thought, here it is, I’m going to live with them, live through them, until the day this story comes out into the light. And there’s no way I’m going to let anyone hush it up. We must publish it. And soon!”

Jonathan smiles and says her name. “Iona.”

She suddenly feels she has known this man for a very long time. She is so familiar with his frown, his smile, his discreetly greying hair about the temples, and she feels that she probably knows his awkwardness

and his weaknesses too. She recognises what he is, and is comfortable with that; but it’s subtle, as if it comes from some recess in the back of her mind.

As their eyes meet, a phone rings somewhere in the house. Jonathan turns round; it’s the phone in the living room. He lets it ring until it stops and the room becomes quiet again.

They grin. Her dimple is deep. The air in the winter house becomes sweeter, thicker; it collects between Jonathan and Iona and links them. She knows there is something precious in this moment, something to do with love, in this space, right now. She feels like crying. This feeling is so fragile, so discreet, and yet it seems mutually acknowledged without either of them saying another word. For a while, in this space, all they hear is the wind shaking the windows, and the soft hush of snow falling on the apple tree in the garden.

NINE | WOMEN WITHOUT MEN

Hai di lao yue.

It’s not likely to fish the moon out from the bottom of the sea

.

SONGS OF YONG JIA ZHENG DAO

, SHI YUAN JUE (WRITER, TANG DYNASTY, EIGHTH CENTURY)

1

Buckingham Palace

London, SW1A 1AA

Mr. Kublai Jian

Lincolnshire Psychiatric Hospital

2 Brocklehurst Crescent

Grantham NG31

Dear Mr. Kublai Jian

,

I am pleased to inform you that I have received your letter regarding your situation at the Lincolnshire Psychiatric Hospital. We are indeed highly sensitive to your plight, and are most sympathetic towards your personal predicament. However, your demand concerns a sphere of action beyond the remit of the obligation of one’s duty as monarch. Regrettably, no legal or diplomatic assistance can be extended to you under the circumstances. We are cognisant that your case will be duly processed by the UK’s Home Office Immigration Department

.

Be aware that as monarch, and head of the Church of England, we are serenely beyond prejudice against, or partiality towards, your person, and you can rest assured that fairness and impartiality will prevail, as is proper for our situation. We are told that the population of the UK has reached 62 million, 18 per cent of whom comprise ethnic groups, with 22 million nonwhite British citizens. We are truly living in a multicultural society. Therefore, one believes you will manage to gain solid ground through the legal process

.

Finally, we enclose your CD

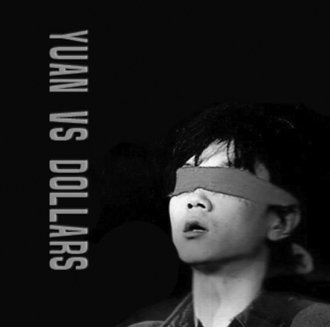

, Yuan vs. Dollars,

as per your request that it be returned. We listened with some degree of interest to this assemblage of undoubtedly authentic ethnic expression. Indeed, we were amused. We believe your musical career will continue to flourish despite your current difficulties. We wish you a swift resolution of your present setbacks

.

Yours truly

,

Elizabeth R

2

Deng Mu

35 Thistle House, Tudor Lane

London E2 7SF