I Have Landed (29 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

A few years ago, some enlightened soul experienced a flash of insight that should have occurred to myriads of travelers decades ago: Why not list flights by cities of destination rather than times of departureâand then use temporal order as a secondary criterion for all flights to each city? Then travelers need only scan an alphabetical list to find Chicago and its much shorter and far less confusing array of temporal alternatives. Listing by city of destination has now virtually replaced the old criterion of departure time at our nation's airports. The transition, however piecemeal, both within and among airports, took only a few yearsâand life has become just a bit less stressful as a result. The innovator of this brilliant, if tiny, improvement deserves the “voice of the turtle” medal for easing life's little pains (see the Song of Solomon for a full list of the small blessings that lead us to “rise up . . . and come away” to better places).

I suspect that two important and linked properties of cultural change lead to long persistence of truly outmoded and inconvenient systems, followed by rapid transition to something more sensible. First, the outdated modality arose for a good reason at the time, not by mere caprice. A lingering memory of rationality might help explain the great advantages afforded by simple incumbency in both politics and ideology. (I suspect that listing by time of departure made evident sense when the train, or the stagecoach in earlier times, passed through town along the only road, and all travelers went either one way or t'other: “The southbound stage, did you say, sir? Do you want to take the 10:30, the 3:00, or the 5:15?”)

The old way, having worked so well for so long, will

persist faute de mieux

until oozing change finally makes the world sufficiently different and some bright soul gets inspired to say: “We can do much better at essentially no cost or bother.” The ease of the change and the obvious character of the improvement then induce the second feature of great rapidity, once thought breaks

through the thick wall of human stodginess. In locating a biological analogy to express the speed of such a transition, I would seek an appropriate metaphor in the concept of infection, not evolution.

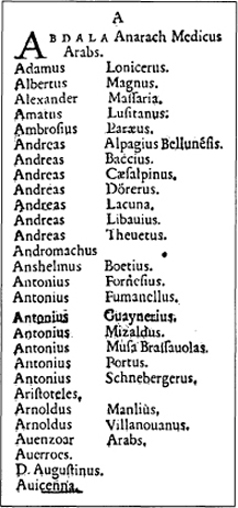

Caspar Bauhin's 1613 bibliography, arranged alphabetically, but by the authors' first names

.

I mention this phenomenon because, in an accident potentiated by browsing through old books (a grand and useful pleasure that we must somehow learn to preserveâor, more accurately, keep possibleâin the forthcoming world of electronic source materials rather than primary documents), I encountered a remarkably similar example, with an entirely sensible beginning at the birth of modern paleontology in 1546, followed by a troublesome middle period resembling our difficulty in searching through large flocks of flights ordered by time, and ending with a resolution by 1650 that has persisted ever since. How shall the names of authors in scholarly bibliographies be ordered? Alphabetically,

of course (and “alphabetical order” already had a long pedigree), but how particularly, since people have more than one name?

Consider the example that first inspired my interest and puzzlementâthe bibliography from Caspar Bauhin's 1613 volume on the bezoar stone. (The Swiss brothers Caspar (1560â1624) and Jean (1541â1613) Bauhin ranked among the greatest botanists and natural historians of their time. Bezoars are rounded and layered stones found in the internal organsâstomach, gall bladder, kidneysâof large herbivorous mammals, primarily sheep and goats. In the Bauhins' time, both medical and lay mythology attributed magical and curative powers to these stones.)

In an episode of my favorite television comedy classic,

The Honeymooners

, Ed Norton (played by Art Carney), following his promotion to file clerk from his former job in the sewers, gets into terminal trouble for his overly literal method of filing: he places “the Smith affair” under the letter

T

. Bauhin seems to follow a procedure of only slightly greater utility in alphabetizing his sources by their first names. Note his initial entries for the letter

A

The system works well enough for a few classical authorsâthe single-named Aristotle and the greatest scientific philosophers of early Islam, Avicenna and Averroes. Albert the Great (Albertus Magnus), the teacher of Thomas Aquinas, also fares well enough, since Magnus is his honorific, not his last name (although I once received a student term paper that listed him as Mr. Magnus).

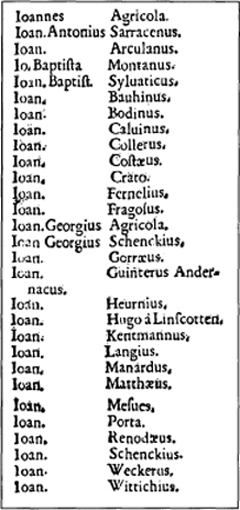

But I don't relish the need to search through a long list of Andreases to find my two favorite contemporaries of Bauhin (from a time when the system of first and last names had already been stabilized in Europe), the chemist Andreas Libavius and the anatomist (and geologist) Andreas Caesalpinus. When we encounter the lengthy list of Johnsâthe most common first name both then and nowâthe system's utility suffers serious deterioration. I have to remember that Caspar Bauhin's own brother bears this name if I wish to honor (and consult) the family lineage. Even worse, how will I ever find my favorite late-sixteenth-century scholar Giambattista della Porta? I must know his first name, then remember that Giambattista is Italian for “John the Baptist,” and finally recognize that, in this Latin listing, he will appear as Ioannus, or just plain John.

(Filing by first name cannot be dismissed as absurd in abstract principle, but only as unworkable in actual practice, because most Europeans share just a few common first names, whereas their far more distinctive last names should be preferred as primary labels for bibliographers. As an interesting modern analog, last names can be quite scarce in Latin countries. Therefore, people who bear one of the more common monikersâthe Hernándezes or the Guzmáns,

for exampleâusually add their mother's last name to their father's primary labelâas in González y Ramonânot for reasons of political correctness but rather for greater distinction in identification.)

How can I find the authors I seek in Bauhin's 1613 bibliography, when I knew them by their last name, but Bauhin lists them by their first name

â

especially when so many folks bear the most common moniker of “John,” as for this entire list!

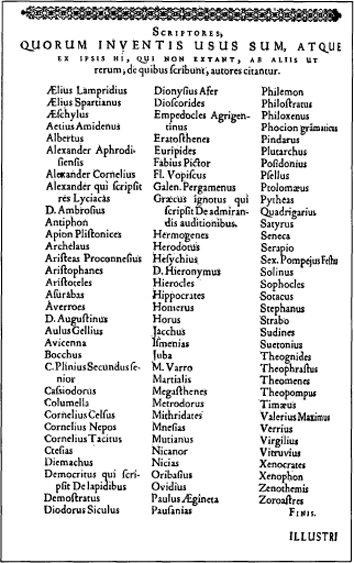

I would have been less puzzled by this obviously suboptimal system for 1613 if I had bothered to ask myself why such a strategy had probably developed as a sensible option in the first place. Instead I found the answer, again by chance, while browsing through the great foundational work of modern geology: the 1546 treatise by Georgius Agricola.

The extensive bibliography of Agricola's

De Natura Fossilium

, the first major treatise on geology under Gutenberg's regime for producing books, uses first names for ordering and spans a wide range of time (from Homer in the ninth century

B.C.

to Albertus Magnus in the thirteenth century

A.D.

) and traditions (from the Greek dramatist Aeschylus to the Persian philosopher Zoroaster). All of Bauhin's ancient

A's

take their rightful places: Aristotle,

Averroës, and Avicenna. But here the system of starting at the very beginning of each name makes perfect sense, because all of Agricola's sources either bear only one name or use the first word of a compound moniker as their distinctive identification.

Agricola, after all, begins the chronological list of modern scholarship. He therefore devotes his bibliography only to sources from antiquityâboth because no two-named contemporary had published anything of note in the field of geology, and especially because scholars of the Renaissance (literally “rebirth”) believed that knowledge had deteriorated following the golden ages of Greece and Rome and that their noble task required the rediscovery and emulation of a lost perfection that could not, in principle, be superseded.

But as scholarship exploded, and the assumptions of the Renaissance gave way to a notion (especially in science) that genuinely new knowledge could be discovered by people now living (and, in another cultural innovation, identified by their last names), the old method of bibliographic listingâordering by the very first letter of each name, no matter which part of a compound name expressed the personal distinctiveness of an individualâceased to make sense. Almost inevitably, the modern system of listing by the most salient markerânearly always the “last” name for people of European extraction but (obviously) retaining the old system for single-named ancientsâgained quick acceptance and became universal by the century's end. In the bibliography from an important chemical treatise of 1671 (the

Experimenturn Chymicum Novum

of J. J. Becher; see page 182), our “modern” system has already prevailed. Agricola now joins Aristotle and Avicenna under the

A

's, and I can finally find my minor hero Caesalpinus under

C

, even if I can't remember his nondistinctive first name, Andreas.

In short, the original bibliographic system in printed scientific books worked well for Agricola in 1546 because all his sources (authors from antiquity) used only one name. But by the time of Bauhin's bezoar book in 1613, the old system no longer made sense, because a fundamental change in scholarly practiceâhonoring new knowledge discovered by living peopleâcombined with a social change in naming, filled Bauhin's bibliographic list with modern, two-named folks still listed by the old system as John, Bill, or Mike. Bauhin, in other words, got stuck in a transient intermediary state bound for imminent extinctionâstill ordering by the time of the afternoon stage for London, when his readers wanted to know the cities first and the times afterward. Within a few decades, some bright soul devised the simple reform (listing by the most salient name) that brought an old institution (the bibliography) into line with a new practice (the relevance and dominance of modern authors).

Agricola's 1546 bibliography alphabetized sensibly by first (and usually only) names because nearly all his sources represent classical authors identified by their initial names

.

The common message of these storiesâthat our traditions may arise for small and sensible reasons but may then outlive their utility by persisting as oddities and impediments in an altered worldâmay strike most scientists as intriguing enough but irrelevant to their own professional practices. We all recognize that organisms, in their evolution, may be hampered by such historical baggage, not easily shed from the genetic and developmental systems of complex creatures now adapted to different environments. Whales cannot jettison their air-breathing lungs, while humans suffer herniations and lower-back pains because upright posture imposes such weight and stress upon weak muscles that, in our four-footed ancestors, never needed to bear such a burden. But

we do not sufficiently honor the analogous principle that scientific ideas, in their history of growth and development, may also be stymied by superannuated beliefs and traditionsâintellectual luggage that should be checked at the gate (and truly lost, on purpose for once, by an obliging airline).

We do eventually amend the worst injustices of our foundational documents, thus avoiding the tragedies of Lincoln's more drastic alternative of armed insurrection: women can now vote, and an African American can no longer count as only three-fifths of a person in our national census. But we do not always shed the burdens of less pernicious irrationalities. We have never, for example, amended the constitutional provision that presidents must have been born within the geographic confines of literal American territory. If your impeccably patriotic parents of Mayflower descent happened to be traveling in France when you decided to make your worldly entry, you had best find another way to place your mark upon history.