I Have Landed (28 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

6. O

STIOCOLLA

, or “bone stones,” shaped like human bones and useful in helping fractures to mend.

But among all stones that advertise their power of healing by resembling a human organ or the form of an afflication, Schröder seems most confident about the curative powers of the

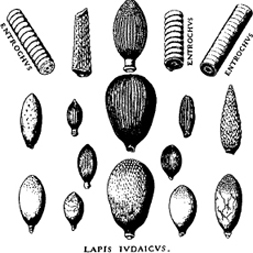

Lapis judaicus

, or “jew stone” (named for its abundance near Palestine and not, in this case, for its shape or form). The accompanying illustration, included in the most beautiful set of fossil engravings from the early years of paleontology (done by Michael Mercati, curator of the Vatican collections in the midâsixteenth century, but not published until 1717), mixes true jew stones (bottom two rows, and center figure in top row) with crinoid stem plates in the top row, each separately labeled as

Entrochus

, or “wheel stones”(for these stem plates, of flat and circular form, even bear a central hole for the passage of an imaginary axle).

In Schröder's world, jew stones provide the mineralogical remedy par excellence for one of the most feared and painful of human ailments: kidney stones and other hard growths in body organs and vessels. Schröder tells us that jew stones may be male or female, for sexual distinctions must pervade all kingdoms to validate the full analogy of human microcosm to earthly macrocosm. The smaller, female, jew stones should be used

ad vesicae lapidem

(for stones in the bladder), while the large, male, versions can be employed

ad renum lapidem expellendum

(for the expulsion of stones from the kidneys). The doctrine of signatures suggested at least two reasons for ingesting powdered jew stones to fight kidney stones: first, their overall form resembled the human affliction, and powdering one might help to disaggregate the other; second, the precise system of parallel grooves covering the surface of jew stones might encourage a directed and outward flow (from the body) for the disaggregated particles of kidney stones.

With proper respect for the internal coherence of such strikingly different theories about the natural world, we can gain valuable insight into modes and ranges of human thought. But our fascination for the peculiarity of such differences should not lead us into a fashionable relativism of “I'm okay, you're (or, in this case, you

were)

okay,” so what's the difference, so long as our disparate views each express an interesting concept of reality, and also do no harm? A real world regulated by genuine causes exists “out there” in nature, independent of our perceptions (even though we can only access this external reality through our senses and mental operations). And the system of modern science that replaced the doctrine of signaturesâdespite its frequent and continuing errors and arrogances (as all institutions operated by human beings must experience in spades)âhas provided an increasingly more accurate account of this surrounding complexity. Factual truth and causal understanding also correlate, in general, with effectivenessâand incorrect theories do promote harm by their impotence. Snake venoms cannot be neutralized by powdering and ingesting stones that look like serpents' tongues (the

glossopetra

of the preceding list)âfor the doctrine of signatures holds no validity in general, and these fossils happen to be shark's teeth in this particular case. So long as we favor an impotent remedy dictated by a false theory, we will not find truly effective cures.

Mercati's mid-sixteenth-century engravings of “jew stones”âfossil sea urchin spines, but then regarded as medicinal rocks useful in curing bladder and kidney stones

.

Schröder's quaintly incorrect seventeenth-century accounts of fossils do not only reflect a simple ignorance of facts learned later. Better understanding may also be impeded by false theories that lead scholars to conceptualize fossils in a manner guaranteed to debar more fruitful questions, and to preclude more useful observations. Schröder's theory of fossils as mineral objects, relevant to human knowledge only when their forms suggest sympathy, and therefore potential therapeutic value, to diseased human parts, relegates to virtual inconceivability the key insight that fossils represent the bodies of ancient organisms, entombed within rocks, and often petrified themselves. At least two controlling conclusions of Schröder's theory prevented the establishment of this

sine qua non

for a modern paleontology.

First, the theory of signatures didn't even permit a coherent category for fossils as ancient organismsâand a truth that cannot be characterized, or even named, can hardly be conceptualized at all. In Schröder's taxonomy, fossils belonged, with no separate distinction, to the larger category of “things in rocks that look like objects of other realms.” Some of these “things” were organismsâ

glossopetra

as shark's teeth;

lapis lyncis

as internal shells of an extinct group of cephalopods, the belemnites;

ostiocolla

as true vertebrate bones; and jew stones as the spines of sea urchins. But other “things,” placed by Schröder in the same general category, are not organismsâ

aetites

as geodes (spherical stones composed of concentric layers, and formed inorganically);

ceraunia

as axes and arrowheads carved by ancient humans (whose former existence could not be conceived on Schröder's earth, created just a few thousand years ago); and

haematites

as a red-hued inorganic mineral made of iron compounds.

Second, how could the status of fossils as remains of ancient organisms even be imagined under a theory that attributed their distinctive forms, not to mention their very existence, to a necessarily created correspondence with similar shapes in the microcosm of the human body?

If aetites

aid human births because they look like eggs within eggs; if

ceraunia

promote the flow of milk because they fell from the sky; if

glossopetra

cure snake bites because they resemble the tongues of serpents; if

haematites

, as red rocks, stanch the flow of blood; if

ostiocolla

mend fractures because they look like bones; and if jew stones expel kidney stones because they resemble the human affliction, but also contain channels to sweep such objects out of our bodiesâthen how can we ever identify and separate the true fossils among these putative remedies when we conceptualize the entire motley set only as a coherent category of mineral analogs to human parts?

I thus feel caught in the ambivalence of appreciating both the fascinating weirdness and the conceptual coherence of such ancient systems of human thought, while also recognizing that these fundamentally incorrect views stymied a truer and more humanely effective understanding of the natural world. So I ruminated on this ambivalence as I read Schröder's opening dedicatory pages to the citizens of Frankfurt am Mainâand the eyes of this virtually unshockable street kid from New York unexpectedly fell upon something

in shvartz

that, while known perfectly well as an abstraction, stunned me in unexpected concrete, and helped me to focus (if not completely to resolve) my ambivalence.

Schröder's preface begins as a charming and benign, if self-serving, defense of medicine and doctors, firmly rooted within his controlling doctrine of signatures and correspondence between the human microcosm and the surrounding macrocosm. God of the Trinity, Schröder asserts, embodies three principles of creation, stability, and restitution. The human analogs of this Trinity must be understood as generation to replenish our populations, good government to ensure stability, and restoration when those systems become weak, diseased, or invaded. The world, and the city of Frankfurt am Main, needs good doctors to

assure the last two functions, for medicine keeps us going, and cures us when we falter.

So far, so good. I am a realist, and I can certainly smile at the old human foible of justifying personal existence (and profit) by carving out a place within the higher and general order of things. But Schröder then begins a disquisition on the “diabolical forces” that undermine stability and induce degenerationâthe two general ills that good physicians fight. Still fine by me, until I read,

in shvartz

, Schröder's description of the most potent earthly devil of all:

Choraeam in his ducunt Judaei

âthe Jews lead this chorus (of devils). Two particularly ugly lines then follow. We first learn of the dastardly deeds done by Jews to the

Gojim

âfor Schröder even knows the Hebrew word for gentiles,

goyim

(the plural

of goy

, nationâthe Latin alphabet contains no “y” and uses “j” instead).

Schröder writes in full:

His enim regulis suis occultis permissum novit Gojim, id est, Christianos, impune et citra homicidii notam, adeoque citra conscientiam interimere

â “for by his secret rules, he [the Jew] is granted permission to kill the

goyim

, that is the Christians, with impunity, without censure, and without pangs of conscience.” But, luckily for the good guys, Schröder tells us in his second statement, these evil Jews can be recognized by their innately depraved appearanceâthat is, by

nota malitiae a Natura ipse impressa

(marks of evil impressed by Nature herself). These identifying signs include an ugly appearance, garrulous speech, and a lying tongue.

Now, I know perfectly well that such blatant anti-Semitism has pervaded nearly all European history for almost two thousand years at least. I also know that such political and moral evil has been rationalized at each stage within the full panoply of changing views about the nature of realityâwith each successive theory pushed, shoved, and distorted to validate this deep and preexisting prejudice. I also knowâfor who could fail to state this obvious pointâthat the most tragically effective slaughter ever propagated in the name of anti-Semitism, the Holocaust of recent memory, sought its cruel and phony “natural” rationale not in an ancient doctrine of harmony between microcosm and macrocosm, but in a perverted misreading of modern theories about the evolution of human variation.

Nonetheless, my benign appreciation for the fascinating, but false, doctrine of signatures surely received a jolt when I read, unexpectedly and

in shvartz

, an ugly defense of anti-Semitism rooted (however absurdly) within this very conception of nature. More accurate theories can make us free, but the ironic flip side of this important claim has often allowed evil people to impose a greater weight of suffering upon the world by misusing the technological power that flows from scientific advance.

The improvement of knowledge cannot guarantee a corresponding growth of moral understanding and compassionâbut we can never achieve a maximal spread of potential benevolence (in curing disease or in teaching the factual reality of our human brotherhood in biological equality) without nurturing such knowledge. Thus the reinterpretation of jew stones as sea urchin spines (with no effect against human kidney stones) can be correlated with a growing understanding that Jews, and all human groups, share an overwhelmingly common human nature beneath any superficiality of different skin colors or cultural traditions. And yet this advancing human knowledge cannot be directed toward its great capacity for benevolent use, and may actually (and perversely) promote increasing harm in misapplication, if we do not straighten our moral compasses and beat all those swords, once anointed with Croll's sympathetic ointment to assuage their destructive capacity, into plowshares, or whatever corresponding item of the new technology might best speed the gospel of peace and prosperity through better knowledge allied with wise application rooted in basic moral decency.

When Fossils Were Young

I

N

HIS FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS, IN 1861,

A

BRAHAM

Lincoln expressed some strong sentiments that later guardians of stable governments would hesitate to recall. “This country, with its institutions,” he stated, “belongs to the people who inhabit it. . . . Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it, or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it.” Compared with these grand (and just) precepts, the tiny little reforms that make life just a tad better may pale into risible insignificance, but I would not disparage their cumulative power to alleviate the weariness of existence and to forestall any consequent movement toward Lincoln's more drastic solutions. Thus, while acknowledging their limits, I do applaud, without cynicism, the introduction of workable air conditioning in the subways of New York City, croissants in our bakeries, goat cheese in our markets (how did we once survive on cheddar and Velveeta?), and supertitles in our opera houses.

Into this category of minuscule but unambiguous improvements I would place a small change that has crept from innovation to near ubiquity on the scheduling boards of our nation's airports. Until this recent reform, lists of departures invariably followed strict temporal orderâthat is, the 10:15 for Chicago came after the 10:10 for Atlanta (and twenty other flights also leaving at 10:10), with the 10:05 for Chicago listed just above, in the middle of another pack for the same time. Fine and dandyâso long as you knew your exact departure time and didn't mind searching through a long list of different places sharing the same moment. But most of us surely find the difference between Chicago and Atlanta more salient than the distinction between two large flocks of flights separated by a few minutes that all experienced travelers recognize as fictional in any case.