I Love You, Ronnie (3 page)

Our engagement photo; from MGM, February 1952.

W

hen I met Ronnie, my picture career was really starting to take off. I’d come to Hollywood after a few years of working in the theater—first in small Smith College productions, then in summer stock during college vacations. My mother had been an actress, and the theater life had always appealed to me.

In those days, summer stock was very good training. You didn’t act right away; first, you did a little bit of everything. That way, when you finally did get onstage, you had an idea of what went on offstage to get you there. I cleaned out dressing rooms (you could tell a lot about people from the way they left their dressing rooms); I upholstered furniture; I put on backstage music, I put up signs about the theater in the towns where we toured. My first part, when I did get onstage, consisted of the classic line “Dinner is served.” It was all very, very good experience.

After college, I started acting on the “subway circuit” in the outer boroughs of New York. I even made it to Broadway once, working with Mary Martin and Yul Brynner in

Lute Song.

After someone with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer saw me in the TV drama

Broken Dishes,

I was asked to come to Hollywood for a screen test and, as a result, was signed to a seven-year contract. At the time of my first date with Ronnie, I was filming

East Side, West Side

and working with Ava Gardner, Cyd Charisse, Barb Stanwyck, Van Heflin, and James Mason. For me, this was all very exciting. My role as a pregnant woman in

The Next Voice You Hear

came soon afterward, and I received top billing for the first time. It opened at Radio City Music Hall. The studio sent me to New York, and I took a picture of the marquee with my name on it. I was thrilled, to say the least.

In those days, if you were under contract to a studio, the studio was your life, six days a week. If you weren’t making a movie—and I made eight for MGM—you were doing publicity for one you

had

made. That could mean traveling or even letting the cameras into your home, as I once did, when MGM set up some publicity shots of me moving into my apartment with a group of my studio friends. Pretty much all my friends were from the studio then. There wasn’t much time to see anyone else.

When I was making a movie, I’d have to be on the lot at 7:30

A

.

M

.—women always had early calls for hair and makeup—which meant that I had to be up extra early to drive myself to work. Unlike in today’s world, you drove your own car to the studio. You knew that you had arrived when you could drive onto the lot and park the car there. Otherwise, you had to leave your car at the gas station nearby.

I’d stay on the lot until five or six every evening. And then, even on the days when I wasn’t working, I’d come in and visit other sets.

That was one of the joys of being under contract:You could go onto any set and watch people work, which was something I liked to do, because you could learn a lot.

Ronnie was always supportive of my work, and he enjoyed my growing success along with me. When I was given my own dressing room—a sign that I had arrived at MGM—he gave me a gold key, with instructions to have it cut to fit the lock.

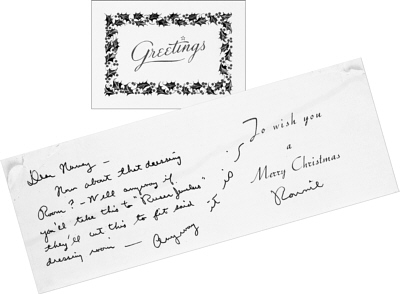

When I was given my own dressing room at MGM, Ronnie gave me a key to it, along with this card.

Dear Nancy—

How about that dressing Room?—Well anyway if you’ll take this to “Ruser Jewelers” they’ll cut this to fit said dressing room.—Anyway it is To wish you a Merry Christmas

Ronnie

My career was bubbling along—and I enjoyed it. And who knows, I might have ended up with my name over the title for years, but then I would have ended up with no Ronnie. He was quickly becoming the center of my life. I had never felt so strongly about anyone before.

We dated all throughout 1951, and by the end of the year we were together all the time whenever Ronnie wasn’t traveling. Whenever he was traveling, no matter how busy I was, I felt lonely and sad. We were just so happy together and so very comfortable in each other’s company. We talked and laughed easily together, just as we had ever since our very first date. We very quickly saw that we both wanted to live the same way and liked to do the same things.

Like all other dating people in Hollywood in those days, we spent time at first going out to nightclubs like Ciro’s and Macombo and LaRue’s, but neither of us was really crazy about nightlife. The glamour was fun, but we preferred to be with good friends or to be at my apartment on Hilgard Avenue in Westwood, having dinner, watching television, and popping popcorn.

When we did go out to eat, our regular spot was Chasen’s, which was very comfortable and less formal than Ciro’s and Macombo. We always sat at the same booth there—that booth is now on display at the Reagan Library—and we always had a warm welcome from the restaurant’s owner, Dave Chasen, and his wife, Maude.

Dave Chasen had been a vaudevillian. His first restaurant was a tiny little place where he made only chili, and it became a hit with the picture crowd. Eventually, though, a few of the actors who had backed him went to him and said, “Dave, you’re giving us stomach problems. You can’t just have us eating chili.” They’d ask for chicken, and he’d run down the street and get some chicken someplace and bring it back. After a while, he just expanded.

I had a wonderful German woman named Frieda who came in to clean for me, and when she knew Ronnie was coming for dinner, she’d stay and cook dinner for us. He’d bring a bottle of wine.

Even after Ronnie and I were married and I’d stopped working, one thing never changed: I didn’t cook. I still don’t. For some reason, I was great with pancakes, waffles, French toast, but three times a day might be a little much.

Dave Chasen knew that I wasn’t a cook, and I suppose it worried him a bit. So when Ronnie and I got married, he sort of took me under his wing. At that time, he was one of only two restaurateurs in town who went down to the meat-packing district and picked out his beef and supervised the cutting of it himself. “Nancy,” he said to me, one day not long after our wedding. “Why don’t you come with me and I’ll show you how to pick out good meat and how to have it cut.” Of course I said yes, and down we went. He was a dear man.

—

The quiet life that Ronnie and I had together wasn’t like any he’d known before, but he liked it, and I did too. We started spending more and more time on the ranch in Northridge, sometimes staying out until evening to have dinner with Nino and his wife, Ruth. Nino would always call Ronnie when a mare delivered, and we’d rush out—it was so exciting and the foals were always so darling, so wobbly at first. Before long, Ronnie taught me to ride horses. (“Show him who’s boss,” he said to me the first time I got up on a horse. That’s ridiculous, I thought. This animal knows perfectly well who’s boss and it isn’t me.) I took some spills—one, I remember, landed me right on my bottom—and I never became a great rider. But Ronnie rode, so I did too. I was, I suppose, a woman of the old school: If you wanted to make your life with a man, you took on whatever his interests were and they became your interests, too.

And so when Ronnie bought Yearling Row, his first ranch in Malibu, I went out and took it upon myself to paint his picket fences. That was no small job: It was a 360-acre ranch! I painted into the sunset, until there wasn’t a single streak of light left in the sky. At the end of each day, I’d take off my blue jeans and they’d be so caked with paint that they’d almost stand up on their own. My skin would be in similar condition. One day my makeup man at Metro said to me: “I have to tell you, Nancy, this is a first: I’ve never had to make up an actress at Metro and first remove paint from her face.”

The house at the ranch was really pretty sad; it had no foundation, and it listed, but we tried to clean it up so it was a little usable. It had what we called a pool—a pretty broken-down pool. But with all that land, it was a wonderful place to walk and ride. I remember, when Grace Kelly married Prince Rainier of Monaco, Ronnie read somewhere that the whole kingdom of Monaco was 360 acres, too. He said, “Do you realize that Yearling Row is the same size as Monaco, and you could be Queen Nancy and I could be King Ronnie?”

Ronnie loved to do outdoor work on the ranch. He was always looking around him and seeing new things he could do. He built all the fences, as he would again on the ranch we had later near Santa Barbara. There, when we’d go riding, he’d look around and comment on the trees, saying how he could make them look even better with some trimming. Then, of course, he would go up and trim the trees—and they

would

look better. We painted the interior of the Santa Barbara house and laid the tiles. He did the roofing. He just liked working with his hands—he always did.

After two years had gone by, marriage began to seem inevitable to both of us—and, I suspect, to Michael and Maureen as well. Gradually, I’d come to spend more and more time with them, and my relationship with them had become very easy and natural, which made me very happy. I’d go with Ronnie to visit them at Chadwick, their boarding school. I’d also be with Ronnie on Saturdays when he picked them up to go out to the ranch. In the car, we’d have lots of fun singing and playing games. Ronnie taught us all “La Marseillaise,” and Mermie and I sang a duet to “You’re Just in Love” until, I think, we drove Mike and Ronnie crazy. Ronnie had a game where he’d pretend he was a little dog and could listen in on conversations from the telephone wires, and he’d make up all these stories of conversations he’d supposedly heard. Ronnie had a station wagon, and we played another game where whoever saw another station wagon first had to yell it out. I don’t know why we didn’t have an accident—we were so busy looking for these station wagons. Then, on the drive home from the ranch, we’d always stop and get a bottle of apple cider at a place Ronnie had discovered, and ice cream cones—not to be consumed at the same time, of course!

It’s difficult to get ready to marry a man who has children—difficult for both sides, because the children have their own feelings. But I think we all handled it well. I remember when Maureen named the first foal born at Yearling Row Nancy D. It thrilled me. I felt that it was a very warm welcome into the family.

By the end of 1951, wherever we went, reporters popped the question “When are you going to get married?” I was beginning to wonder, too, and I was beginning to get impatient. I knew that I wanted to spend my life with Ronnie, and time was marching on. I had long conversations about it with my mother, who listened and advised me. We were always very close, and I couldn’t really talk about these things too much with my friends.

But still, there was no proposal. So, in January 1952, I decided to give things a push.

“I think maybe I’ll call my agent and see about getting a play in New York,” I told Ronnie. As I recall, he didn’t say anything, but he looked surprised. Not long afterward, while we were having dinner in our usual booth at Chasen’s, he said, “I think we ought to get married.”

I was ecstatic. I could have jumped out of my seat and yelled, Whoopee! But I could hardly do it at Chasen’s.

So I answered calmly, “I think so, too.”

Getting our marriage license.

At a Guild board meeting, Ronnie whispered to Bill Holden, “How would you like to be my best man at Nancy’s and my wedding?”

Bill shouted, “It’s about time!”

We announced our engagement in February. Before, Ronnie had called my father to ask for his blessing. Ronnie got three picture offers immediately after our engagement was announced, and we had a terrible time fixing a wedding day. Every time we thought we’d found a date, his work would get in the way. Finally, the date was set: March 4, 1952.

The press had been after us for so long, so many questions had been asked about when we were going to get married and where we were going to get married, that now neither of us really wanted a big to-do. We particularly didn’t want reporters following us around on our wedding day. So we decided on a simple ceremony at the Little Brown Church in the Valley, with only our best friends, Ardis and Bill Holden, attending. The Little Brown Church was small and out of the way and seemed like a good place to be married quietly. Ronnie had found it; he belonged to the Hollywood Christian Church, but that was huge and would have attracted a lot of attention.