ICAP 2 - The Hidden Gallery (3 page)

Read ICAP 2 - The Hidden Gallery Online

Authors: Maryrose Wood

They were, however, prone to mischief, especially when in high spirits. “As are most children,” Penelope thought resignedly. “But that is no excuse for destructive behavior.”

“Your apology is accepted, children,” she said aloud. “Now, let us start tidying up this messâ”

“Mrs. Clarke say, âTorowoo,'” Alexander interrupted, with the barest hint of a frown.

“And wave skirt,” Cassiopeia added, demonstrating with the torn curtain.

Beowulf added nothing further to these arguments, but pressed his lips together unhappily to prevent himself from chewing. The children had apologized, but clearly they also felt that an injustice had been done, for why should they be scolded for playing matador

when the housekeeper was not?

Penelope began to explain. “I do realize that Mrs. Clarke was just now imitating a bullfighter, and therefore you must have thought it was a splendid idea and an enjoyable way to pass the time. And it is, certainly, but only within reason. Do you understand?”

The three Incorrigibles looked at one another. It was plain that they did not understand, and who could blame them? “Within reason” is not the sort of place one can easily find on a map; in fact, its location may vary considerably from one day to the next. It was only when Penelope tried to explain such notions to the Incorrigibles that she realized how the precise meaning of “getting carried away,” “taking things too far,” “going overboard,” and other, similar figures of speech were all woefully hard to pin down. Alas, once the room was a shambles, the curtains ripped, and the pillows emptied of feathers, their meaning became all too clear.

Mrs. Clarke also tried to shed light on the matter. “It's true I was saying âToro, toro,' but only to describe to Miss Lumley something that happened between our master and mistress. So I wasn't playing bullfighter at all, you see. I was telling a story. It's a whole different business.”

“Metaphor?” Cassiopeia inquired.

“Minotaur, silly!” Mrs. Clarke patted the child indulgently on the head. “Aren't you a bright little thing, though?”

Penelope felt the time had come to put a stop to this conversation. “Never mind, children; your apologies are accepted. Now make up your beds, just as they were before you started to play minotaurâ¦I mean, metaphorâmatador!â¦and fold up the red curtain neatly so I may give it to Margaret to be sewn. If you can get all that done and settle yourselves calmly in your chairs near the hearth within, say, ninety seconds”âshe took out a pocket watch to mark the timeâ“I will read aloud to you.”

As the children scrambled to do as they were told (for, like most children, they dearly loved to be read to), Penelope reached into her apron pocket and withdrew a small volume. “My former headmistress, Miss Mortimer, has sent us a guidebook describing all the important sights of London. It should provide us with an excellent preparation for our trip.”

“Sights and sounds are all very well, but I prefer a nice lady's hat shop myself,” Mrs. Clarke said, with a dreamy look on her face. “And a confectioner's. A bit of money in hand and a half day off on alternate Sundays,

that's all the preparation I need.”

Whether Mrs. Clarke was truly in need of a confectioner's shop was a matter of opinion, but Penelope was too busy timing the children to comment. “Eighty-eightâ¦eighty-nineâ¦ninety. Well done! Now, come sit down and let us begin.

Hixby's Lavishly Illustrated Guide to London: Compleat with Historical Reference, Architectural Significance, and Literary Allusions

,” she said, reading off the cover. “What a marvelous gift.”

“Ahwoooooosions!”

the Incorrigibles howled in agreement. Then all four eager pupilsâfor Mrs. Clarke secretly liked to be read to as wellâgathered 'round to listen.

T

HE

HIXBY'S

G

UIDE

HAD COME

by return post as soon as Miss Charlotte Mortimer received the letter confirming that Penelope and the children would be heading to London. It was both a practical and a fashionable gift, for at the time, guidebooks were all the rage, and there were scores of them available on every conceivable topic: from Audubon's

Birds of America

to Zachary's

Taxonomy of Badgers, with Their Cubs, Accurately Figured

.

Fans of ferns could choose from among dozens of

best-selling titles, including Frondson's

Pteridomania for the Beginner, with a Preface on Spores by Dr. Ward.

(It should be noted that ferns were wildly popular in Miss Penelope Lumley's day, much more so than in our own.)

As for travel guides, there were Black's

Picturesque Tourist

guides to England, Scotland, and Wales, and Harvey's indispensable

On the Cheap: Touring the Continent on Five Pence a Day

. Few would risk crossing the Atlantic without a copy of Appleton's

Railroad and Steamboat Companion. Being a Traveler's Guide Through the United States of America, Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. With Maps of the Country Through Which the Routes Pass, in the Northern, Middle, and Eastern States

, a book whose title was as grand and cocksure as the New World it so thrillingly described.

There were scores of books about London, naturally, but in the note accompanying her gift, Miss Mortimer assured Penelope that

Hixby's

was by far the best of the lot, and she should use no other to find her way around town. As the title promised, the volume was lavishly illustrated with thumbnail-sized watercolor paintings, most of which depicted wildflower meadows and snowcapped mountain peaks. Neither of these seemed likely to be a prominent feature of the city.

However, the pictures were attractive, and Penelope liked them a great deal. She found herself admiring them during the long carriage ride to Ashton Station, where she and the Incorrigibles would soon be boarding the train to London.

“In fact,” she told the children as they stood in line to buy tickets, “these miniature paintings are so delightful that I think our very first excursion must be to the British Museum. According to Mr. Hixby”âand here she thumbed her way to the appropriate pageâ“we are to âavoid the crowds that throng before the more well-known works, and concentrate on obscure galleries for the discerning visitor.'”

She showed the page to the children so they could admire the illustration (it was a very pretty lake scene). “Mr. Hixby calls Gallery Seventeen, Overuse of Symbolism in Minor Historical Portraits, a âmust-see.'”

“Then we must see it,” Alexander replied, and Beowulf yapped in agreement. Penelope corrected him with a glance, whereupon he said, “Yes, we must,” just like a proper English schoolboy. Cassiopeia, still sad from her tearful leave-taking with Nutsawoo back at Ashton Place, was silent. She remained so until they were done purchasing their tickets at the ticket window and had walked outside to the platform to wait

for their train. Then she began leaping up and down.

“Torowoooo!” she yelled, pointing. “Torowoooo!”

“I doubt you will see any matadors on the train platform,” Penelope remarked. “If we were traveling to Spain, perhaps. Or to a costume ball.”

But it was the steam locomotive itself that had over-heated the little girl's imagination. It was one of the new shiny red Bloomer engines, a flashy piece of engineering and full of pep, too. (Returning briefly to the subject of guidebooks: For technical specifications on the Bloomer, there is no better reference than

Craswell's Opinionated Guide to British Steam Locomotives

. Alas, copies are notoriously hard to come by.)

“Torowoooo!” The boys took up the cry, pointing and jostling each other. “Torowoooo!”

Penelope looked, and although she did not howl “Torowoooo!” like the children, she was just as impressed. The locomotive was a gleaming scarlet, with a forbidding front grille of inky black. Two shiny gold smokestacks rose above. Truth be told, the appearance of the Bloomer was not unlike a black-nosed, golden-horned, bloodred bull, snorting and puffing steam out of its nostrils and its tall, glittering horns.

When the conductor sounded three deafening, mournful hoots on the train whistle, the children

covered their ears and howled even more loudly in protest. “All aboard,” the conductor cried. “This is the London and North West Railway, eleven oh seven train to London, making all local stops. Final destination will be Euston Staaaaayshun!”

Clutching their second-class train tickets, Penelope helped the children up the steep metal stairs. It was just the four of them; Lady Constance and Lord Fredrick would be driven to London by private coach in a day or so, as soon as Lord Fredrick put his business affairs in order. The servants had gone ahead with the luggage so that they might unpack and prepare the house for the family's arrival.

“Metaphor! Metaphor!” Cassiopeia kept shouting as they boarded the train. The child was doubly mistaken, for in the first place she meant matador, and in the second place there was no matador, just a bright red steam locomotive. But in anotherâone might even say, metaphoricalâway, she was perfectly correct, since a train whisks its passengers from here to there in much the same way that a metaphor carries one idea into another (turning a squabble between husband and wife into a bullfight, for example).

If Penelope had been paying full attention, she might have pointed this out to the children and made

a fine lesson from it. But her mind was on a different train ride altogether. “How interesting it is,” she mused as she settled the children into their seats. “Ashton Place felt so strange to me when I first arrived here from my familiar, beloved Swanburne, on a train very much like this one. And now Ashton Place is home, and London is the strange new destination.”

Then another, related thought occurred to her: What would it be like to see Miss Charlotte Mortimer again? Penelope felt she was scarcely the same person she had been at Swanburne. She was no longer a student; now she was a teacher like Miss Mortimer. She had grown taller and filled out a bit; this she knew from the fit of her clothes.

“Dear me, I hope she does not ask me to call her Charlotte!” Penelope thought in alarm. “It would be terribly awkward, after thinking of her as Miss Mortimer for all these years. Yet I suppose that is how life goes.” Penelope closed her eyes, for she felt suddenly drowsy. “New things become familiar with time, and familiar things become strange. It is very curious and”â

yawn

â“tiring to think of.”

Already the train was having its inevitable nap-inducing effect. The three Incorrigibles were out cold, nestled in a heap on the seat, and Penelope was ready

to follow their example. As the train wheels

clickity-clack

ed along, Penelope's head slowly leaned back against the seat. Her eyelids grew heavy until finally they fluttered closed.

The copy of

Hixby's Guide

began to slip from her loosening grasp. Now it lay in her lap, jostled back and forth with every lurch of the train. From there it would soon fall to the floor with a

thud

â

Grrrrrrrrrrr!

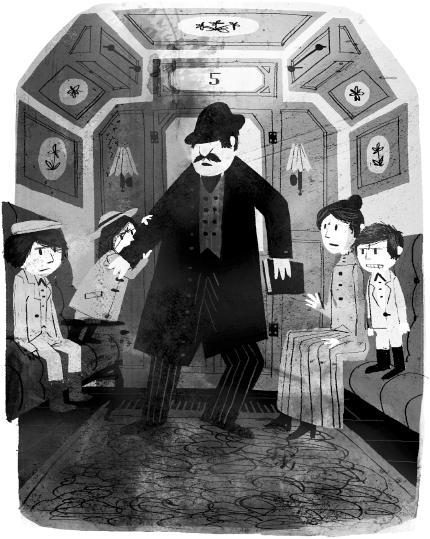

Penelope startled awake to behold a most unexpected scene, in which all three Incorrigibles played prominent roles. Alexander's teeth were bared to the molars. Beowulf was growling like a mad thing, and Cassiopeia's jaws were locked on to the sleeve of a man in a long black coat, who was trying unsuccessfully to shake her off.

“I beeg yer pardon!” the man said heatedly. “Miss, could you call uff your cheeldren? The gurl is aboot to draw blood.” His accent was hard to place.

“Children, whatever is going on?” Penelope cried.

“Man steal book,” Alexander said in a fierce, low voice. His eyes were fixed on the intruder. The fellow was tall and rotund, with a misshapen nose and a hat pulled low over his eyes.

Penelope glanced down at her lap. Her

Hixby's Guide

was gone. Frantically she looked around the seat and floor. Then her eyes traveled upward to the man's arm, still held fast by Cassiopeia's teeth buried in the coat sleeve. The book dangled between his fingers.

“I will take that back, thank you,” she said curtly, snatching the book away.

“It was falling to the floor, miss. I only mint to kitch it and put it on the zeet next to you while you sleeped,” he said in his inscrutable accent. “The flur is so dirty and demp, it would be have been rooned.”

“Thank you kindly for your trouble.” Out of the corner of her eye Penelope noted that the children were still on high alert. What animal instincts did they have, she wondered, that made them know when danger was present?

“Is ridikalus book in any case,” the man pressed on. “Full of mistikes and out of deet. If you like, I will geev you my copy of

Parson's Pictorial Pamphlet Depicting the City of London and Environs, Second Edition,

and tek this worthless tome off your hends.”

“A moment ago you were afraid it would be ruined. Now you say it is worthless. I find your arguments somewhat contradictory.” Penelope smiled in a way that was not at all friendly; it was a trick she had learned from Lady Constance but had never before had reason

to use. “I thank you again for your trouble. Good day.”

“Man steal book!”

“Good day,” Alexander repeated through bared teeth; as a result the phrase, while socially useful, was not very well pronounced.

“

Grrrrrrr

day,” said Beowulf, most unpleasantly.

“Let go of the man's sleeve, dear,” Penelope instructed. Cassiopeia obeyed with reluctance. There was a small rip and a half-moon-shaped wet spot in the fabric where her mouth had been. Under different, friendlier circumstances Penelope might have offered to have the coat mended, but these circumstances were not those. Penelope drew the children close to her and regarded the man with what she hoped was a stern and fearless gaze.

The man lingered briefly, as if he would say more. With a parting glance at the

Hixby's Guide

âdid Penelope imagine it, or was it a longing, greedy, covetous sort of glance?âhe left.

Cassiopeia wiped her mouth on the hem of her dress. A tiny, bright green feather came unstuck from her lips. She held it between two fingers, then blew it into the air. They all watched as the downy tuft wafted hypnotically back and forth, back and forth, until it disappeared under the seat.

“Yukawoo,” Cassiopeia remarked before curling up

next to her brothers once more. “Taste like pillows.”

The three children quickly drifted back to sleep. Penelope did not. She remained anxiously alert for the rest of the trip, holding tight to her

Hixby's Guide

and ready, frankly, to pounce.

Â

“L

ONDON

, E

USTON

S

TAAAAAAAY

SHUN

!”

“Hold hands, children, hold hands!” The passengers stampeded out of the train like a herd of cows that were late for a very important milking appointment. Penelope clutched her carpetbag with one hand and Alexander's sweaty fingers with the other. Alexander held tightly to Cassiopeia, and Cassiopeia held just as tightly to Beowulf. In this white-knuckled way, the three groggy children and their nervous governess snaked through the crowd, searching for an exit.

Penelope could not help trying to catch a glimpse of the strange man who had tried to steal her

Hixby's Guide

. She did not see him, but in such a large crowd it would have been nearly impossible to find anyone. The thought made her squeeze Alexander's hand so tightly that he yelped.

“It was an unpleasant incident, nothing more,” she thought bravely. “I ought not to make too much of it, for pickpockets and rogues are a commonplace in

London. We must stay on our toes, that is all.”

With that settled, Penelope turned her attention to a more immediate concern: finding her way to Number Twelve Muffinshire Lane, which was the address of the house Lord Fredrick had rented. She knew that London was a large, bustling, and confusing city, and that one wrong turn might send them wandering down dark cobblestone streets that dead-ended at smelly slaughterhouses and riverfront establishments of ill repute. However, there was a foldout map in the back of her guidebook, and the children were skilled trackersâat least when in a forest.

Once the foursome had elbowed their way out of the station, Penelope tried to get her bearings by holding the map open and spinning it 'round until it resembled the maze of streets that crisscrossed before her. The sidewalks outside Euston Station were even more crowded than the interior of the station had been. Passersby jostled Penelope this way and that, making it difficult to keep the book open to the correct page. Not only that, but the foldout map was so charmingly decorated with pretty alpine meadows, it was impossible to read the street names.