ICAP 2 - The Hidden Gallery (8 page)

Read ICAP 2 - The Hidden Gallery Online

Authors: Maryrose Wood

“Penelope, do you believe in the supernatural?”

“There was a time I did not.” Miss Mortimer looked uneasy. “But as Agatha Swanburne once said, âAn open mindâ'”

“âLets ideas out, as well as in.' I know.” Penelope's thoughts began picking up speed all on their own, like a ball rolling downhill. “Do you mean to suggest that there

is

some curse on Ashton Place? Or that the Gypsy might know something about the person who wishes ill to the children? For I have already sent an inquiry to a recent acquaintance, whom I hope can arrange an interview with the old woman. Never fear, Miss Mortimer! I am determined to get to the bottom of it all.”

“No!” Even though Miss Mortimer kept her voice low, there was no missing her sharp tone. “Penelope, you must obey me in this. Do not go around asking questions. When I invited you to lunch, I had resolved to give you a general instruction to be on your guard; I felt it was prudent. I did not want the children here because I did not want them to be frightened. But your news about the fortune-teller's warning took me by surprise, and I have already

revealed more than I should.”

She looked at Penelope intently. “About curses and prophecies I will say nothing more. But you must take this to heart: It is in your best interest, and that of the children, that you not seek to know any more about this unfortunate business than you do right now.”

“Butâ¦âA Swanburne girl is curious!' âA Swanburne girl asks questions!'” Penelope protested, reciting the very maxims her headmistress and the other teachers at Swanburne had instilled in her.

Miss Mortimer smiled. “Believe me when I say: On this particular point, no one would agree with me more than Agatha Swanburne herself.”

“But how am I to protect the children if I do not know what kind of danger they are in, or from what source?”

Miss Mortimer took another bite and gestured for Penelope to do the same. “The same way you have protected them so far. By having faith in them and seeing the best in them, and teaching them to see the best in themselves. Why, if you had not shown such compassion and love to the Incorrigible children, how would they have ever been able to make a friend of Nutsawoo?”

“Nutsawoo?” Now Penelope felt hopelessly

confused. “What does that silly little squirrel have to do with any of this?”

“âNo one's fate is written in India ink,' as Agatha Swanburne once said.” Miss Mortimer underscored the point by gesturing with her fork. “The hunt is on, indeed. But the hunt can end in unexpected ways. The Incorrigibles and Nutsawoo have already taught us that much. Do you understand?”

Penelope thought back to the night of the holiday ball, and the mad chase Nutsawoo had led through the house, with the children in pursuit. She remembered how desperately she had tried to find them, and how convinced she was that the Incorrigibles were about to make a gruesome snack of the poor wayward squirrel.

“I think I do understand,” she answered slowly. “You mean that even when the outcome seems inevitable, something unexpected can still happen? And so it might be better not to know too much about what has been foretold so that one might keep an open mind, so to speak?”

Miss Mortimer nodded. “It is all too easy for most people to simply march in step toward whatever future they believe lies in store. But many forces shape a person's destiny, Penelope,” she added. “And a prophecy

made before you were born cannot take into account the greatest influence of all.”

“Which is what?”

The headmistress smiled again. “You. Your own character. The kind of person you choose to beâand that you inspire others to be.”

Penelope frowned. “Are you sure there is nothing more I can do, then?”

“Quite sure. Be brave and be true, be the best governess you can be, and give the future a chance to rewrite itself accordingly.” Miss Mortimer gestured with her fork. “And be optimistic, Penny! For the unexpected does, quite frequently, happen. As the poet said, âThe best-laid plans of wolves and men gang aft agley.'”

“You mean mice,” Penelope gently corrected. “Not wolves and men. Mice and men.”

“Mice, mice, of course. How silly of me.” Suddenly nervous, Miss Mortimer reached for her tea. Her hand trembled, but her voice remained firm. “Now, let us speak of this no more, and enjoy a marvelous meal. Tell me, have you begun reading the Giddy-Yap, Rainbow! books to the children yet? Heavens, I remember reading them to you, when you were scarcely bigger than Cassiopeia!”

Â

T

HE FIDDLEHEADS

P

HILIPPE WAS FOLLOWED

by fruit salad Philippe, fried fish Philippe, fettuccine and fennel Philippe, and numerous other courses, each one more tasty than the last.

Miss Mortimer scraped the last bite of fondue Philippe from her plate. “Genius,” she said decisively. “Chef Philippe has truly outdone himself today, don't you agree?” She laid down her fork and dabbed her lips with the napkin. “Before I forget, Penelope, I have something for you.”

Penelope was about to protest, for she had not thought to bring a gift for Miss Mortimer. But when she saw the small, familiar packet that Miss Mortimer removed from her reticule, she understood.

“I must ask that you continue to use the hair poultice I gave you.” Miss Mortimer pressed it into Penelope's hands. “I brought you another packet so you will not run out.”

The truth was, Penelope had not bothered to open the last packet of hair poultice that Miss Mortimer had sent. And, reallyâif the Incorrigibles were in some kind of danger, why waste time worrying about the condition of Penelope's scalp? But she knew her former headmistress well; for whatever reason, this business about Penelope's hair seemed to be a matter of real

importance to Miss Mortimer, and there would be no argument.

“Do you promise to use it?” There was a teasing twinkle in Miss Mortimer's eye, but she was intent on securing Penelope's sworn promise. “On your honor, as a Swanburne girl?”

“Well, I suppose⦔

“Promise me, Penelope.”

“Yes, yes! I promise. I will use it.” Penelope sighed. Though she was far from vain, the thought of returning to her former lackluster hair was not very appealing, especially after receiving that nice compliment from Simon Harley-Dickinson.

“Excellent. I know you will keep your word, Penelope, as you always have in the past.” Miss Mortimer was already perusing the dessert menu. “Flan Philippe, figs in phyllo Philippeâeverything sounds delectable. But when at the Fern Court, one must order the tarte Philippe. No other dessert compares. By the way, how do you like the

Hixby's Guide

?”

Penelope was in no mood for dessert. Both the meal and the conversation had been a great deal to absorb, and she was feeling quite overstuffed, in head, heart, and tummy.

“No, thank you; I am too full for tarte Philippe,

Miss Mortimer,” she said politely. “As for the

Hixby's

, I am grateful for the gift, of course. Yet, I confess, I find it a curious volume. For example, it is supposed to be a guidebook to London, but the pictures all seem to be of Switzerland, or someplace similar. And a great many of the entries are in the form of little poems.”

“That is curious.” Miss Mortimer was still fixed on the dessert menu. “They say that the head bakers from the finest patisseries in Paris come to the Fern Court, take one bite of tarte Philippe, and collapse, weeping with envy.”

Penelope sighed. “I think I will just have another cup of tea.”

“No dessert? What is the matter, dear?” Miss Mortimer put the menu down. “You look pale and sad all of a sudden.”

In fact, there was something troubling Penelope. It had occurred to her halfway through the frosted flakes Philippe, and now she was not sure how best to raise the subject, other than to simply plunge ahead. So she did.

“Miss Mortimer, as you know, it has been many years since”âthe word “parents” felt so strange on her tongue she had to will herself to say itâ“my parents left me in your care.”

Penelope glanced down and saw that she was twisting her napkin into knots. “Perhaps they do not realize that I have already graduated. Perhaps they have lost track of time. But it is still possible that they intend to return for me, someday. And now that I have left Swanburne, I would not wish⦔ All at once Penelope found that her throat had tightened, and it was hard to speak. “I would not wish for them to come back looking for me and not find me there.”

“Have no fear,” Miss Mortimer said quickly. She, too, seemed to be misty-eyed all of sudden; perhaps it was a consequence of some errant fumes from the onion soup being served at another table. “I intend to remain headmistress at the Swanburne Academy for many a year to come. Should anyone of interest inquire as to your whereabouts, I will put you in touch with them directly.”

Penelope nodded. “Thank you for your reassurance. That solves the matter completely.”

It did not, of course. It had been more than ten years since Penelope had been deposited at Swanburne's doorstep. No letters, no birthday or Christmas presentsânot even a picture postcard had arrived during that long span of time. Any ordinary person would have given up hope that the long-lost Lumleys ever

intended to come back.

Of course, Penelope was far from ordinary. Much as a well-trained seal can keep one ball spinning on its shiny black nose while balancing another upon its tail, for all those years she, too, had managed to balance two somewhat contradictory beliefs: First, that, since her mother and father would undoubtedly come back for her one day, their long, unbroken silence was not something for her to feel lonesome or sad about; and second, that in the meantime, Penelope ought to go about her affairs exactly as if her parents were not in the picture at all, for, in fact, they were not.

It was not an easy trick, for the clever seal or the plucky young governess. But if there was one thing Penelope had learned from her headmistress, it was that worry, self-pity, and complaint were not how a Swanburne girl got through the day. Instead, just as one might use a ribbon to hold one's place in a fascinating book that one is temporarily forced to put down, Penelope simply made note of her confused and disappointed feelings and then put them gently to the side, for there was nothing to be done about them at present.

At the same time, she observed that the mere act of posing this question about her parents to Miss

Mortimer seemed to have lessened the heavy, burdened feeling inside her, the one she had assumed was the result of eating too much food Philippe.

“I believe I will have dessert after all,” Penelope announced as she shook out her napkin, refolded it, and placed it neatly across her lap. “Followed by biscuits, and more tea. Shall I summon the waiter?”

W

HEN THEY PARTED

,

Miss Mortimer gave Penelope precise directions for taking the omnibus so she would not have to walk all the way back to Number Twelve Muffinshire Lane.

Penelope had a great deal to think about along the way. There was the tarte Philippe, a dessert so indescribably delicious that Penelope found herself literally unable to describe it. And this business about the children being in danger was perplexing, to say the leastâbut, as Miss Mortimer had made clear, there was

nothing for Penelope to do about it but continue being the good, careful governess she had already proven herself to be.

“Which is how I intended to proceed in any case,” she thought, peering above a sea of hats to see where they had stopped, for the omnibus was crowded. “Though I am not sure I like Miss Mortimer's advice to not ask questions. After all, was it not Agatha Swanburne who said, âThe more one asks, the more one knows, and the more one knows, the more one asks'?”

Then there was her reluctant (oh, how reluctant!) promise about the hair poultice. Just when her hair was starting to attract compliments! Just when she had met a person of the male variety who might be inclined to notice such things! But a promise was a promise. Perhaps she ought to buy herself a new hat while in London. There were certainly many styles to choose from, judging from the array of plumed and beribboned specimens she could see bobbing and nodding around her.

“Or perhaps the poultice could wait a short while to be applied, just until we return to Ashton Place.” The vehicle lurched its way 'round a corner so quickly the passengers swayed like trees in a storm. “For, being a gentleman, Mr. Harley-Dickinson is likely to offer to

escort me to meet that Gypsy woman. It would only muddle things to alter my appearance now. After all, Miss Mortimer asked me to use the poultice; she did not specify when⦔

Much as the omnibus proceeded in an orderly fashion from one stop to the next, Penelope, too, thought about all these different topics in turnâdessert, danger, hair, Simonâsorting them out as best she could, and then moving on. When she had finished her route, so to speak, and her mind was free to wander, Penelope found herself dwelling yet again upon the subject of her mother and father. Although obviously far from perfect, clearly, the Lumleys were not the absolute worst parents in the world. That title surely belonged to the parents of the Incorrigibles, whoever they were.

“At least

my

parents had the sense to leave me in the care of a well-regarded educational institution,” Penelope told herself as she pictured her three pupils, barking and gnawing and baying at the moon. “

My

parents knew better than to abandon me in the woods to fend for myself, with only wild animals as my companionsâpardon me!” she cried aloud suddenly. “Excuse me, driver! I believe we have reached my stop!”

Â

A

S SHE ALIGHTED FROM THE

omnibus at the corner of Muffinshire Lane, Penelope was startled by a familiar yet enigmatic grunt.

“Good day, miss.”

“Timothy!” she exclaimed (for Penelope was not so rude as to address the strange, watchful coachman as Old Timothy to his face). Then, without thinking, she blurted, “What are you doing here?”

He snorted. “I've just delivered Lord Fredrick Ashton to the humble cottage he's paid a king's ransom to rent. I trust that meets with your approval, governess.”

“I apologize. I did not mean to speak so abruptly.” Penelope quickly composed herself. “It surprises me to see you here in London. You seem so much a part of Ashton Place; it is jarring to think of you in town.”

“People don't always stay where you put 'em, miss,” he replied darkly. “As a governess, you ought to remember that.”

His tone made Penelope shiver. “What do you mean?”

“Those children, for instance. You won't find them in the nursery where you left 'em, that's for sure.” He turned and began walking back to the house with his quick, rolling gait. Penelope scurried after him.

“Excuse me! What do you mean, the children are

no longer in the nursery? I left them in Margaret's care, and I have only been gone an hour, or perhaps twoâ¦.” Though even as she said it, Penelope realized it had been closer to three hours since she had left the house. All that thought-provoking conversation and the culinary brilliance of Chef Philippe, not to mention the long walk to the Piazza Hotel and the bumpy ride back, had eaten up a substantial portion of the day.

“You've been gone three and one-quarter hours. Not that I've been keeping track.” He looked straight ahead as they walked. “The children went on an excursion, with Margaret and some young fellow I never saw before.”

Penelope's breath caught. “Do you mean Mr. Harley-Dickinson? Tall but not too tall, with gentle waves of brown hair, finely formed features, and the gleam of genius in his eye?” she said in a rush.

“Yup,” the coachman grunted. “That's the one.”

Misery! Simon had come, and she had missed him! And now he was out for the day with Margaret and the Incorrigibles! A pang of some unfamiliar feeling poked at her insides, someplace not too distant from her heart. It was like a dull, throbbing ache, or a sharp, twisty, stabbing feelingâoh, why were things becoming indescribable all of a sudden?

By now Old Timothy had gotten ten paces ahead of her. Once more she ran after him. “Please, one more questionâdo you happen to know where they went?” For she would not be content until she could see with her own eyes that all three children were safe and sound, and preferably doing something educational.

The coachman turned and looked at her with one eye half closed, and the other so wide open as to look as if it had just seen a ghost. “I believe they were going to the zoo.”

“The

zoo

? But that is the very last place they ought to go!” Penelope cried.

“What's the trouble, miss? Most tykes love the zoo. Why should these three be any different?” Did Penelope imagine it, or was Old Timothy suppressing an evil chuckle? “Now I've a tasty errand to run. Here's my stop. Enjoy your day.”

And with that he ducked into the nearest doorway, which Penelope saw was the entrance to a small shop called the Charming Little Bakery. Under different circumstances, and if she were not still feeling so spectacularly well fed, Penelope would have been interested in sampling the wares of this promising-sounding establishment. But her mind was fixed on the Incorrigibles.

“The zoo! Dear me, they could hardly have picked a worse place to go! I must find the children at once!” she resolved. But how exactly did one get to the zoo? The answer came in a flash.

“Miss Mortimer is proven right again: Having a guidebook is essential when visiting a strange city. I will dash up to the nursery and fetch my

Hixby's

. Surely it will contain directions to such a popular destination.” With that, she lifted her skirt and broke into a run, and did not stop until she reached Number Twelve Muffinshire Lane.

Â

T

HE SCIENCE-MINDED AMONG YOU WILL

no doubt recall Newton's First Law of Motion, which (among other things) predicts that a distraught governess traveling at high speeds over a slippery surface will continue to do so until some greater force conspires to stop her. Mrs. Clarke had been right to scold Margaret; the wooden floors of the foyer had been polished to such a high degree of slickness that Penelope's feet flew out from beneath her the moment she burst through the door.

“Ah-

whoops

!” she cried, as most people would under the circumstances. Arms flailing, Penelope skidded down the hall on what the French would politely call her derriere, past the stairs and straight into the

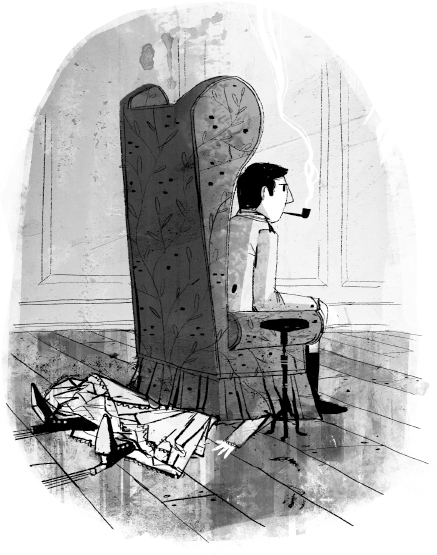

drawing room, where Newton's greater force lay ready and waiting: an overstuffed armchair containing the seated form of Sir Fredrick Ashton, the unimaginably wealthy and incurably nearsighted master of Ashton Place. Penelope slid almost completely beneath the chair before she finally came to a stop. Only her feet poked out from the back. Lord Ashton seemed oblivious to her arrival.

“Constance, can't you be more understanding? I've business to attend to. Men's business. And the club's accommodations are far more suitable for that sort of thing than this ridiculous frou-frou of a house, what?”

“But you have only just arrived! Really, Fredrick, it has been unbearably dull here. I have not set foot out of the house and have had no callers, not one! And there is no one to talk to except the servants.”

“You mustn't talk to the servants, dear, unless you're ordering them about. It undermines your authority.”

“What do expect me to do all day, then? Shop?”

“If you like. Just don't spend too much.”

“But I thought the whole point of being rich was that nothing was too much!”

Thud.

“Ow!” Penelope yelped involuntarily, for she had bumped her head on the bottom of the chair in an

attempt to crawl out from underneath.

“Did you hear something?” Lord Ashton looked behind him and on both sides of the chair. “Anybody back there? Stop or I'll shoot, ha ha ha!”

Unlike her husband, Lady Constance had eyesight enough to tell whether or not a set of human limbs was sticking out from beneath the furniture. She marched around the chair and planted both hands on her hips.

“And whose plain and sensible shoes are these?” she demanded. “The rest of you, come out at once!”

Meekly, Penelope pushed herself into view. “Pardon me,” she said, clambering to her feet with as much dignity as she could muster, given the awkward circumstances.

Lord Ashton squinted in Penelope's direction. “See, there

was

someone there! Is it a burglar? No, wait, you're the governess, what?”

“Yes, Lord Ashton. I was on my upstairs to the nursery, and I, er, slipped. I apologize for the intrusion.” She curtsied and started backing toward the door.

“Not so fast, Miss Lumley.” Lady Constance had the look of a gathering storm. “Did you know the post has been delivered twice already today?”

“Why, yes. I imagine it has been.” Penelope was unsure where this conversation might be headed, but

she hoped it would be brief. The thought of the Incorrigible children at the zoo was still foremost in her mind, and she was determined to grab the

Hixby's Guide

and rescue them as soon as possible.

“Did you hear something?” Lord Ashton looked behind him and on both sides of the chair.

“Have you checked the mail tray, by any chance?”

“No, my lady.” Penelope swallowed hard. “I have been out.”

“I see.” Lady Constance's voice was dangerously controlled. “If you could spare a moment from your busy social calendar to examine its contents, you will discover it contains yet another envelope addressed to you. Your letter has been lying there, taunting me, all day long!”

“I am sorry, Lady ConstanceâI did not intendâ”

Lady Constance made a dramatic gesture to silence poor Penelope. “As if yesterday's impertinence was not enough! Once again, Miss Lumley, it seems you are

in receipt of mail

.”

“Mail? Zounds! I almost forgot.” Lord Fredrick jumped to his feet and began patting his pockets. “Constance, dear, I've an invitation for you, somewhere. Baron Hoover handed it to me at the club; it's from his wife. Where did I put it? Maybe it will take your mind off spending my money for an afternoon, what? If I can find the blasted thing, that is⦔

Lady Constance's mood changed on the instant. “An invitation? Really? Oh, Fredrick, that is the best news I have had since arriving in London! Hooray, hooray!”

“Waitâ¦waitâ¦here it is.” From his vest pocket he removed a small envelope of heavy cream-colored stock. “Let that keep you busy for a while, eh? See you later, dear. Don't wait up.”

He gave her an indifferent peck on the cheek and strode out of the room. Penelope, too, thought she might take the chance to leave. “Good day, ma'am,” she murmured. She was nearly out the door when Lady Constance squealed and seized her by the arm.

“Oh,

look

! Do you see this envelope, Miss Lumley? This is from the Piazza Hotel! Simply the most exclusive hotel in London! Home of the Fern Court and the legendary Chef Philippe! I would not expect that someone of your social station would have heard of him, but trust me, he has no peer when it comes to the use of a whisk. They say he makes a positively indescribable dessertâ”

“Tarte Philippe,” offered Penelope, to move things along. Just imagining what might be going on at the zoo this very minute was more than she could standâall those grim-faced bears, hungry lions, and wild-eyed baboonsâ¦.

“I beg your pardon?” Lady Constance looked stunned.

“Tarte Philippe, the indescribable dessert⦔ Penelope stopped, for it occurred to her that it might be wise to downplay her firsthand knowledge of this tasty treat. “That is only a wild guess, of course, given that the chef's name is Philippe.” She smiled and shrugged, as if to say, “These crumbs on my skirt and the tiny fruit stain on my sleeve have nothing whatsoever to do with the actual tarte Philippe I greedily devoured not two hours ago.”