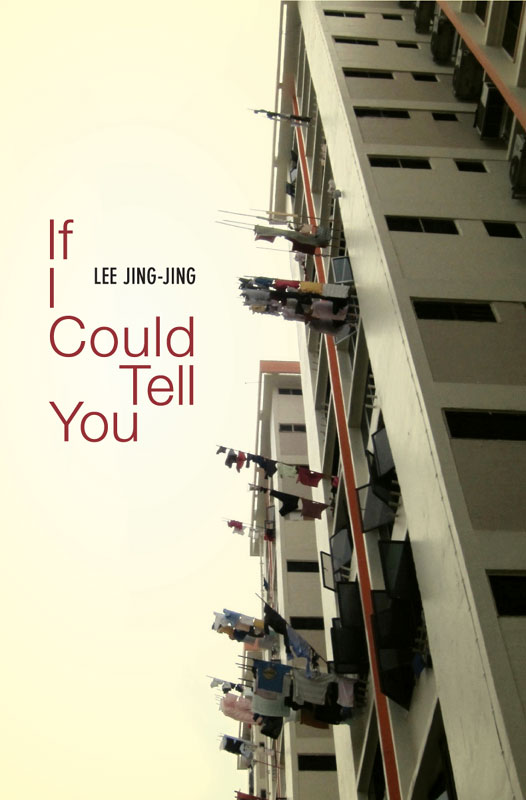

If I Could Tell You

Read If I Could Tell You Online

Authors: Lee-Jing Jing

© 2013 Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited

Supported by the National Arts Council, Singapore

Published by Marshall Cavendish Editions

An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International

1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196

Cover art by Cover Kitchen Co. Limited

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Requests for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited, 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196. Tel: (65) 6213 9300, fax: (65) 6285 4871. E-mail:

[email protected]

. Website:

www.marshallcavendish.com/genref

The publisher makes no representation or warranties with respect to the contents of this book, and specifically disclaims any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose, and shall in no event be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Other Marshall Cavendish Offices

Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 99 White Plains Road, Tarrytown NY 10591-9001, USA • Marshall Cavendish International (Thailand) Co Ltd. 253 Asoke, 12th Flr, Sukhumvit 21 Road, Klongtoey Nua, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand • Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Times Subang, Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Marshall Cavendish is a trademark of Times Publishing Limited

National Library Board, Singapore Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Lee, Jing-Jing, 1985-

If I could tell you / Lee Jing-Jing. – Singapore : Marshall Cavendish Editions, c2013.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-981-4435-99-4

1. Public housing – Singapore – Fiction. 2. Home – Singapore – Fiction.

3. Singapore – Fiction. I. Title.

PR9570.S53

S823--dc23 OCN819310610

Printed in Singapore by Times Printers Pte Ltd

For Marco,

my home

“A multitude of people and yet solitude.”

— Charles Dickens,

A Tale of Two Cities

HE STEPS OUT OF HIS SHOES, THE WAY HE DOES EACH time he arrives home, the round tips of each meeting the wall. Home, he thinks, he’s home. He won’t leave.

EARLIER that day, Boss gave Ah Tee a large paper bag packed full with ground coffee, tins of sweet milk, a loaf of bread, coconut jam, mincemeat buns, and a carton of eggs laid carefully on top, narrow ends pointing up. Once the bag was safely nestled in his arms, the older man pressed into his palm an

ang pow

, a red packet. For good luck, he said, looking at the half-torn posters on the wall. He turned around to face his car as if to make sure it was still there, then turned back to look at the poster again, at the young woman wrapped in a slinky black dress holding a bottle of beer up against her face. It was to her that Boss said, take care of yourself, good luck. He said this over and over, never looking at Ah Tee, even as they shook hands in front of the coffee shop, its shutters already drawn down and locked even though it was only two in the afternoon. There was no one left to feed.

Ah Tee waved as Boss went into his car, the family waiting in the cool interior. Watched as the two children sitting in the back turned and shouted words he couldn’t hear and waved wildly at him through the rear window. Watching even when the car was just a fading blue smudge in the distance. He stood there for a while, both arms wrapped around the paper bag. Then he turned to walk the little way to the lift. The jingle of his change purse marking his every step. His shod feet clapping against the concrete.

He passed two other shops on his way. A hairdresser’s and a grocery store. Both closed; their owners had found some place else to set up their businesses and relocated long ago, unlike Boss, who decided to sell up, work for a larger chain of coffee shops — the money was better, he said, and it was less work. He looked abashed when he told this to Ah Tee, said he would try to get him another job, he would. That was months ago. Nothing had come of it.

Ah Tee guessed the time to be just past two. Ten past, at most. It used to be his favourite time of day, the hours between two and four. Everything was quiet then, and he could sit and rest his feet after the madness of breakfast and lunch, running from table to table, taking drink orders and cleaning up spills. From two to four he could sit and watch nothing happen, it was so still. The quiet bothers him now. He steps into the lift, listens to the clank of metal as it lurches upwards. The building might hear him and know, he thinks. But when he gets to the top floor and the lift doors rumble open, there is no one there. Most of the residents on this floor have moved into their new place and he goes through the empty corridors, leans against the parapet. He notices a few clouds in the distance, the ones with a tinge of grey and yellow, like a troubling bruise. Looks like rain, he thinks.

This place. He grew up here. He has lived in Block 204 all his life.

He steps out of his shoes, lines them on the floor like he does each time he arrives home, the round tips of each meeting the wall, scuffed heels touching. The imprints of his feet have been ground into the tender soles, the cotton worn thin after years of walking and shuffling. He grew up here, he thinks. He won’t leave.

FOR months, it was filled with coming and going. The pacing back and forth of everyone. The carrying of tables and mattresses and things which had to go across corridors and all the way down stairs, the men dripping, chests heaving at the end of it. I watched them put their lives on the backs of trucks, strapping them down with tarp and rope and driving away. Young ones sitting on top of a chest of drawers laid on its side, holding on to the side rails with clammy hands. The neighbours, the ones who helped, wave until the truck rolls away, through the narrow, curving driveway and out of sight. Then they walk into the lift, go up, back behind their doors, into their little boxes. To take care of their own moving away.

All the while they did this, they left bits of themselves. Threw up parts of their home outside their doors. Sacks bulging with unwanted clothes, the fallen out stuffing of old toys. Books yellowed, their spines pristine and unlined or tender and ripped, neatly stacked at first, but now fallen into a heap on the floor. Shoes belonging to feet now overgrown. They threw it all out, letting it clog the walkways, pile up at lift landings so that the cleaners sighed and shook their heads. Jabbed their brooms at the mess but could not or would not do anything about it. They have been growing so much, it is difficult to get around, to get into the lifts.

The only people left are the old, the poor, people who have had trouble finding a new home. Or those who put it off because it didn’t seem real until officials came with sheets of paper to paste on all the doors. Sheets of paper that used clipped, official words to say, this home it is not yours anymore you have until the end of the month.

Everyone here, they all know this.

The boy on the second floor leaving home, jingling the keys in his pocket to make sure they’re there and then closing the door behind him. He loops a length of raffia string around his hand, letting the black and tan dog at the other end of it tug him forward along the corridor, towards the staircase. The dog goes too fast down the steps and he grabs the railing and laughs. Ma would love him, he thinks, she would.

The girl on the sixth, smoking to the very end of her cigarette, calling out, could you bring me another Coke? I’ll just start the DVD to get over the boring parts. She drops the finished cigarette in an old tin can put on the coffee table just for that purpose, leans back on the sofa and waits.

The man on the eighth, jamming his keys into the door. It takes a while, his hands are shaking so much. When he finally gets into his flat, the quiet of it makes him jump even though he knows his wife is at work. She shouldn’t be here, should she? Still, he goes through the rooms saying, Kim, Kim. Calling out and wanting a reply, not wanting a reply. He doesn’t know which.

The old lady on the ninth floor who lives on her own, in a flat choked with everything she has brought home over the years. Rusty fans which don’t work anymore, stacks of newspapers from long ago, which line up against the wall, fill the air with the sharp scent of ink. She counts the flattened cardboard and empty soda cans she has collected that day, puts them by the door so she wouldn’t forget to bring them away in the morning.

The man from the tenth. The lone man, bone thin, bone white, moving through the space in his loose shirt and trousers, past the shuttered coffee shop, past the little store which sold everything before they too moved out. He gets into the lift, presses and lights up the topmost button.

All of them and all the others who are left, wrapping their lives up in paper to put into brown boxes, inhaling borrowed air. Happy only for the breeze, the wind moving along the corridors, past the gaps of the louvered windows, under doors, through the hollows of my inside. It is all quiet. Shut up suddenly. Like the slamming of doors to make a point.

OLD One! Old One, come and see. Something happened, she says.

She shouts through the things around her, abandoned furniture picked from the skip behind the building and hulled back home with the help of her pushcart. Several mismatched chairs, stacks of phonebooks, an open bag of dry cat food which she brings to the neighbourhood strays every morning. A small foldaway table topped with empty pots, papers, a number of biscuit tins with just crumbs in them. All of it make her look smaller than she already is, bent and shuffling across the tiles in her gnarled feet. There is no reply, only the tinny, cracked sound of the radio, an old song about a woman named Rose.