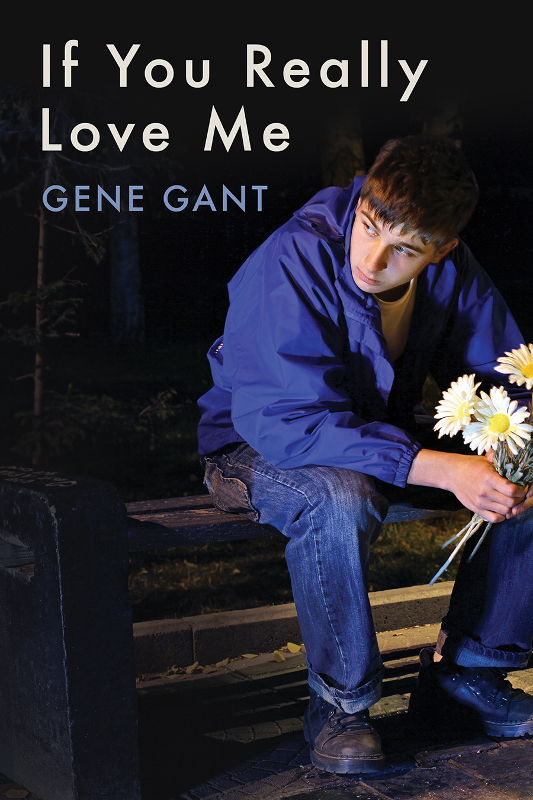

If You Really Love Me

Read If You Really Love Me Online

Authors: Gene Gant

For Leon. Thanks for all the fun times.

I

DON

’

T

have a clue what I’m doing.

Mr. Roberson, the guidance counselor, told me to look through the college brochures at the front of his office. He said it would help me narrow down my career choices. I open the University of Alaska at Juneau brochure to the list of degree programs that institution offers.

Logistics and Materials Management

Audiology and Speech Pathology

Geomatics

Kinesiology and Exercise Science

Applied International Studies

I don’t know what this stuff even means. What the heck does an aquatic zoologist do? Mr. Roberson says I should match my career to my interests so that my future job will be one that I enjoy and find meaningful. I’m addicted to TV. Any jobs out there for professional couch potatoes?

It’s almost the end of October. In about six months, I’ll be graduating from high school. Six months. That’s all the time I have left to come up with a plan.

I need a plan really bad.

The bell is about to ring. I stuff the brochure back into the metal rack and hurry out of Mr. Roberson’s office. The halls are crowded. Kids are at their lockers, or walking along in pairs and groups. Texting. Talking. Laughing. Living. None of them look at me as I make my way up to the second floor. A blank space, that’s me, null and void as far as the other kids are concerned. I’m so far below the radar not even the bullies and the mean girls bother with me.

Teachers like me because I don’t make trouble. I sit at the back of the room, turn in my assignments on time, answer when they call on me, and keep my mouth shut the rest of the time. “Ellis is very well-behaved,” they always write on the report cards they e-mail to Mom. How lame are you when the only good thing even your teachers can say about you is that you’re boring?

On the second floor, I go to my botany class. Most of my classmates are already in the room, some at their desks with noses stuck in books—there’s a test today. Others are standing around, carrying on loud conversations. The teacher, Mr. Corde, never says anything about how much noise his students make before class starts. He’s somewhere around sixty, skinny and gray-haired, and spends his time between classes working crossword puzzles. He gets so wrapped up in them that he doesn’t even seem to hear anything happening around him, at least until the bell rings.

As I walk to the back of the room, I look at the desk one row over and one seat ahead of mine. Empty. My heart ticks up a bit with anxiety. That desk is where Saul Brooks sits. My heart always ticks up in some strange way when it comes to him.

After plopping down in my seat, I dig out my binder and drop my backpack into the desk beside me, which has gone unclaimed for months now. I start looking over the notes I’ve taken in class since the last test. I’ve studied, and I know the stuff coming and going, but I always review my notes at the last minute, sort of a good-luck ritual.

There are footsteps coming my way. I know it’s Saul. He has this way of walking that is soft, almost stealthy, but powerful, the way I imagine a tiger would move. That’s just the way he is. I feel his presence like a change in air pressure from an approaching storm. There is the thick rustle of denim as he slides into his seat. My chest seems to tighten. I don’t look up at him, not right away. I’m careful, because I don’t want to be obvious. I listen instead to the sound of him unzipping his backpack, clearing his throat, sneezing suddenly into his fist. Nobody beseeches God to bless him.

More students walk in. There’s even more chatter. Out of the blue, Kennie Walters, who sits in front of me, goes, “Look out for the fly,” and there’s a flick of motion followed immediately by a loud, thick

whack.

I look up a second later and see Oscar Weir turn around and shoot Kennie a pissed-off glare as he clutches the back of his head with his right hand. It seems that Oscar really wants to pull back and pop Kennie right in the nose, but he has two good reasons for holding off. Reason one: fighting gets you an automatic three-day suspension. Reason two: Oscar’s a little guy, and Kennie’s in the same weight class as a whale. That makes Kennie a dickhead. He laughs in Oscar’s face. A couple of his dickhead friends snicker along with him.

I take advantage of the distraction Kennie has caused to sneak a look at Saul. Saul’s attention has shifted to Oscar, but he turns away now, disinterest plain on his face. He has a dogged case of acne. But even with the acne, Saul has a pretty good face. It’s narrow and angular, and he has light brown eyes, full lips, and a dimpled chin. His skin is pale, but who doesn’t get pale with winter coming on? His black hair is thick and curly. Last March, when he transferred to Northwest High, he kept it cut short. When he came back to school this fall, his hair draped down to his shoulders. He goes days at a time without shaving, walking around with patchy stubble on his face. The stubble and long hair combine to make it look as if he doesn’t give a damn about anything. Then there’s the starched, designer blue jeans, the white sweater and the spotless black loafers he’s wearing today that make him look as if he enjoys being pampered.

He’s about six feet tall with a jockish body, lean and strong like the guys on the baseball team, only he doesn’t play any sport. He never joins the football or soccer games that pop up in the park after school. He’s the kind of guy all the pretty girls would want to date, the kind of guy who would hang out with the too-cool-for-everything dudes. Only nobody ever talks to him. Saul Brooks is what my English Comp teacher would call a study in contradiction.

None of the kids at this school talk to me either, but there’s a difference. They sort of avoid me, ease out of the way when they see me coming, never make eye contact, as if I’m a day-walking vampire out to mind-dazzle them or something. With Saul, kids tried to kick up conversations with him when he transferred in, girls especially. But he always made excuses to cut off the contact, so kids stopped trying to engage him.

I want to engage him.

The bell rings. It has the same effect on the class as a director snapping “Action!” on a movie set. Mr. Corde closes his puzzle book, pops up from his desk, and says, “Good afternoon, everyone. Shut up and sit down.” He crosses the room to close the door as stragglers hurry in and everyone gets settled in their seats.

“Put all books and papers away,” Mr. Corde says. “The only thing that should be on your desk for this test is a pen or pencil.” He scoops up the stack of test sheets from one of his drawers and begins to move through the class, placing a copy face down on each student’s small, square desk. “Don’t turn these over until I tell you to.”

My chest tightens again as I watch Mr. Corde make his way down the aisle toward me. It is the sensation of choking, of suffocation. I don’t know why this happens to me. The feeling hangs on even after Mr. Corde finishes handing out the test, returns to his desk, and tells us to begin. It hangs on as I sail through the test, thirty multiple-choice questions, checking off one answer after another. Fifteen minutes is all it takes, and I’m done.

I wish my chest would open up. This is the last period of the day. It would be nice if I could just hand my completed test over to Mr. Corde and leave. School policy says all students must stay on campus until the final bell. The school probably doesn’t want to get sued over some kid getting pancaked by a car on the school’s watch. So I sit here, rubbing my chest with my hand, while everyone else works away.

I sneak another look at Saul. Instead of marking answers, he’s casually doodling what looks like a woman’s bulging naked breast in the upper right corner of his test sheet. It confuses me when he starts drawing curly lines all over the breast. Then he writes something below the drawing in big, heavy letters:

My hairy left nut.

It must be great not to give a damn.

C

ARY

B

AKER

knows my routine. After I get home from school, I always watch reruns of

Avatar: the Last Airbender

, which I got hooked on when I was a little kid. Nickelodeon runs back-to-back episodes from four to six on weekday afternoons, and I watch every one of them even after having seen them about a hundred times already. Six is when Mom finishes her shift at the restaurant and heads home, so that’s when I turn off the TV, clean up the place, and try to make myself scarce. And that’s when Cary knocks at my door today.

“Looking good there, El,” he says when I open the door. He grins, nodding at my chest. “What happened, man? You took a shower and forgot to take off that shirt?”

The front of my jersey is soaked through. I absently rub my hand over it. “I just finished washing the dishes that were left over from breakfast.”

“You must’ve dried ’em with that shirt.” Cary zips up his jacket. It’s fitting him sort of tight these days. He’s been gaining weight lately. His right ear lobe is double pierced, and he’s wearing the pair of gold loops his mom gave him for his birthday last year. “So are you through being lady of the house?”

“Yeah.” I can see that he wants to hang out. Cary lives in the apartment below mine. His single mom is friends with my single mom. They’re like my family because they’ve always been there. Our moms were very close once, a lot closer than they are now. I remember how they did everything together—shopping, going out, cooking meals—when Cary and I were a lot younger and we all had to live in one apartment. They were like a couple of sisters. This apartment complex is the only home I’ve ever known, and Cary’s mom says he and I used to run around the playground together in our diapers. That’s how long I’ve known Cary, so I can tell when something’s bothering him. Today, he looks worried. “What’s up?”

He shrugs and looks away. “I lost out on another job today,” he says. “You remember that I got an interview last week with the guy who owns the skate rink over in that strip mall on the east side? The one I had to take three buses to get to? He called me today and said thanks but no thanks.”

A stab of sympathy goes through me. Getting rejected is awful. “I’m sorry, man.” I step out onto the balcony, and Cary backs up, making room for me. The metal frame is cold as anything can be; I can feel it in the soles of my feet. My socks got wet, just as my jersey did, and they seem to be freezing around my feet. My toes are already starting to sting from the bite. “You’re gonna find something, I know it. You just gotta hang in there.”

“I need a job like yesterday, man.” Cary turns and sinks down heavily to sit on the stairs of the fire escape. He dropped out of high school last year because he was flunking everything. He turned eighteen last month. He doesn’t want to be a burden on his mom. “I have this nightmare vision that I’m gonna wind up like my cousin Teddy: thirty years old, not working, sleeping on somebody’s couch, and collecting food stamps.”

“You won’t, man.” I sit down in the space next to him. It’s a tight fit. “I know you. You’re not gonna let that happen.”

We live in Ravenna Point, a large city bordered on the east by Lake Washington. It’s south of Seattle and almost directly west of Mercer Island City. It’s also dangerously close to Mount Rainier, an active volcano. There hasn’t been any kind of eruption from Rainier since 1894, and there’s no evidence it’s gearing up to blow anytime soon. But if it ever does, it will bury Ravenna Point under massive, fast-moving mudslides. I was nine when one of my elementary school teachers told me that, and Rainier still gives me nightmares.

Night falls earlier and earlier as we close in on winter. The sky is black with thick, dark gray clouds blocking out the stars. The wind is like subzero, blowing out of the west. It will probably rain tonight, or maybe sleet. I tuck my hands under my arms for warmth. The sounds of the city surround us, traffic noises, voices from the parking lot in front of the building, a siren wailing in the distance.

Cary works up a little smile. “I’m glad one of us has got some confidence in me. How’re things going with you, El? You still hanging in there at school?”

“Yeah. We’ve got midterms coming up in about three weeks, so I’m studying a lot.” I almost tell him that I managed to get my GPA up to a 3.0 on my last report card, but I don’t say it because I don’t want to make him feel bad for flunking out of school. “I’ll be glad when that’s over. Then we’re out for Christmas break.”

“Bet you can’t wait for that. You and your mom got anything special planned?”

“Not really.” It’ll probably be the same as every other Christmas. Mom stopped giving me any gifts for the holiday when I turned thirteen. She said I was too old for that crap. Instead, she’d get me new underwear or socks, stuff she said I needed more than some gadget I’d break in a day and never use again. This Christmas, unless she makes plans with Cary’s mom or one of her other friends, Mom will cook, we’ll eat dinner together, and then she’ll head out to the casino with a couple of her coworkers or maybe go out on a date while I sit in the living room and watch television. “What about you?”