I'm Just Here for the Food (10 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

HOW TO GRILL BY DIRECT HEAT

Despite its mystique, I wasn’t quite ready to buy into the grilling as a snatch-the-pebble-from-my-hand Zen thing. I asked a bunch of cook friends what factor they thought most important in grilling, say, a perfect steak. All five of them said the same thing: heat control. Then I asked them how they knew they had it right. They all said: experience. Having recently seen the film

Memento

, I decided to give myself a problem: what if a person couldn’t make memories and had no way to accumulate experience? Could he or she still grill a New York strip? Perhaps you could load the equation in this person’s favor by identifying a set of controllable factors (time, mass, heat), then provide the tools for their control.

Time was the easy one, so a timer would definitely be part of the kit. I thought too of weighing the steak, but figured that in direct-heat cooking, what really matters is how far the heat is going to travel, so thickness matters more than any other single factor. So I bought a strip and cut myself nine 1½-inch thick steaks. Next, the big one: heat.

Many a grill aficionado judges the heat of the grill with a thermometer mounted in the dome of the grill cover. (Although the thermometer that Weber builds into the handle of their nicer kettle grills seems relatively accurate, I always back it up with another stem thermometer inserted in the top vent.)

That thermometer can only tell me what the cumulative air temperature is inside the dome. That’s great info to have if I’m planning to grill-roast with the cover on. But if I’m planning to grill a couple of steaks, it’s useless. For that I need intelligence from the front lines, so to speak. I need to know what’s going on at the grate. And I’m not going to put my hand anywhere near it, thank you.

I figured that measuring out the charcoal was a good idea, even if it only got us into the ballpark, so I settled on a single chimney’s worth (about one quart of lump charcoal). I fired it up, and once the coals were glowing, I dumped them onto the fire grate. Now what? I tried placing a coil-style oven thermometer right on the grate, but since it’s designed to read air temperature, it got a little confused. Besides, I really needed to know not only the temperature of the radiant heat at grill level but the temperature of the grate itself.

11

I was flummoxed. Standing there staring at the coals had warmed me up, so I went back to the Airstream to ponder the situation over an icy beverage.

Ice melts when its temperature rises above 32° F. That’s a known factor, so one could say that ice is a good thermometer.

Since I knew that the thickness of the food mattered a heck of a lot more than its width or length, I decided to stretch my meat supply by cutting the steaks down to 4-by-4-inch squares that were 1½ inches thick. These I seasoned liberally with kosher salt and allowed to come up to room temperature.

12

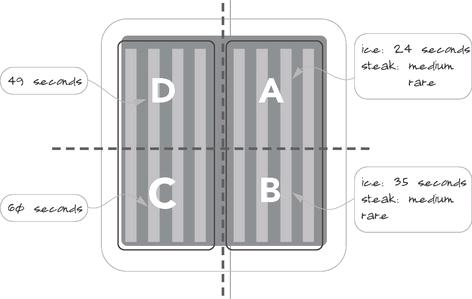

I filled an ice bucket, grabbed a stopwatch, and divided my grill grates into four zones. My plan: select a cooking time and a desired doneness, then finesse the fire until it delivered my steak in that time and to that doneness. Then all I’d have to do is time how long that same fire took to melt a cube of ice and I’d have a measuring stick to steakhood.

I started the test by melting cubes in all four sectors. I used the standard cubes made in ice trays in some 90 percent of American household freezers, shaped like this:

The times were radically different, which I’d expected, given the fact that I hadn’t really arranged the charcoal but let it fall where it may (see illustrations, opposite).

I laid a square steak on each sector of the cast-iron grill grate and hit the timer. I figured that 4 minutes per side was reasonable, so I left them for 2 minutes then rotated them 90 degrees and gave them another 2. At that point I turned over all four pieces (with tongs of course) and let them cook again for 2 minutes, then rotated them for 2 minutes more. I removed them and let them rest for 5 minutes.

Both the steaks from the right side, those from zones A and B, with ice cube melt times of 24 and 35 seconds looked the best, and once sliced, the steaks were very close to perfect: the steak from zone A was on the medium-rare side of rare, and the steak from zone B was on the rare side of medium-rare. Both steaks were darned tasty. The steaks from the slower sectors were undercooked inside and out. I hypothesized from this that if an ice cube melted on the grate in 30 seconds, give or take a couple of seconds either way, you could produce a darned fine steak in 8 minutes, 4 on each side with a twist after 2. Subsequent testings bore this out. At one point, the ice took over 50 seconds to melt so I stopped and added more charcoal; 15 minutes later we were back to 25 seconds and great steak.

Next I wanted to find out how much the grate material itself mattered, so I replaced the cast-iron grates with the standard-issue grate from my Weber and retested.

GRILLING: THE SHORT FORM

•

A clean grill grate is important. You can clean a grate in a self-cleaning oven or use your muscle and a pumice stone.

•

For direct cooking, spread coals in a single layer that extends approximately 2 inches beyond where food will cook, with briquettes barely touching each other. For indirect cooking, place your food over a drip pan and mound the briquettes along the sides of the pan.

•

The number of briquettes needed depends on the size and type of grill you’re using and the amount of food being cooked. A general rule is 30 briquettes to grill 1 pound of meat.

•

Their grayish white color indicates that coals are hot and ready. You shouldn’t see much in the way of smoke or flames because the compounds that produce them are gone.

•

If you need to lower the heat, try raising the height of your grill rack, spacing coals farther apart, covering the grill, or closing the grill’s air vents. On the other hand, if you want to increase the heat, try gently poking the coals or moving them closer together.

•

Once the grill is hot, wipe the grates down with a rag dipped in vegetable oil. Do this every time you use the grill.

•

The best way to tame a flame is to choke off its air supply using the grill lid.

•

Remember, charcoal burns about 200° hotter than a wood fire. Having a fire extinguisher on hand is always smart.

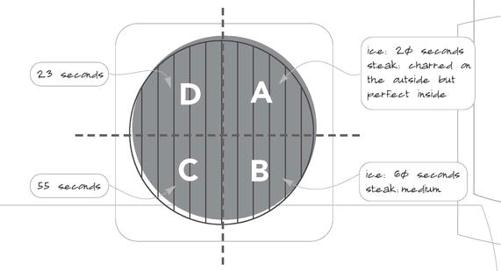

The melt times for the ice cubes were significantly longer—almost twice as long on the thin grate as for the same level of fire under the iron grates. That made sense. Conduction kicks butt when it comes to delivering heat, so the denser mass and greater surface area of the iron grates would deliver more heat to the ice quicker. To compensate for the lack of actual contact, I cranked the fire up physically and put on some more charcoal. Within another 15 minutes the fire was at its hottest.

13

I dropped my ice again and hit the timer.

Hoping to conserve steak, I decided not to split hairs and went with the zone with the highest contrast, zones A and B again. As soon as the meat hit, I knew I’d have to change plans, as the meat in the zone A started popping and blackening around the edges almost immediately. At the 1-minute mark I turned the steak, but held to the 2-2, 2-2 timing of the original test for the steak in zone B. After 2 minutes, I turned the steak in zone A, exposing a surface that I would have called just short of burned. I figured it was toast but went ahead and let it cook another minute, then turned it and let it cook a final minute. I let both steaks rest 5 minutes.

When I sliced the steak from zone A, it was beautiful. As terrible as it had looked sitting on the plate, once cut, it revealed a beautiful red, medium-rare interior that contrasted nicely with the charred edge. Flavor-wise, it was a great contrast of char bite and creamy meatiness. All the tasters proclaimed this as their favorite; the steak from zone B, at medium, came in second.

On a lark, I tossed on even more charcoal, then cut another steak crosswise into 1½-by- 1½-by-4-inch rectangles. I mounted these on steel skewers, 2 per skewer, then salted them rather heavily and let them sit at room temp for 10 minutes. I grilled them on the near-nuclear fire for 1 minute on each side, slid them off the skewers while they were still hot, and rested them for 3 minutes. I sliced them into cubes (again: a great contrast between mahogany exterior and almost rare interior), sprinkled them with balsamic vinegar, ground on some pepper, and served.

The tasters devoured these the fastest despite the fact that they had already gorged themselves on the earlier tests. Turns out that the added surface area allowed for more crust development. And that was a good thing.

SO WHAT WAS LEARNED?

Ice cubes can be used to gauge the heat at the grate level. Using widely spaced bars, arrange the charcoal so that a standard ice cube melts in 30 seconds; cook your meat for 2 minutes, then rotate 90 degrees and cook for another 2. Flip and repeat. Rest for 5 minutes, slice, and serve. If you like more char, consider the narrow bars and coals that will melt the ice in 20 seconds, then cook 1-1, 1-1. Or you can grab your own bucket of ice and figure out what you like. The next time you grill steaks for company they may chuckle when you start grilling ice, but with practice you’ll be able to hit your desired doneness every time. Finally, all other things being equal, meat on widely spaced, dense grates will cook faster than on small, wiry grates.

Despite America’s fascination with hunkin’ hunks of meat, I no longer serve steaks in their whole state. And boy do I have reasons:

• Nine times out of ten, a 12- to 16-ounce steak is too darned much for one person. By slicing a grilled steak, you still get the illusion of “a lot” without plopping half a cow on your plate. Two people can suddenly feel full on what would normally feed one.

• Slices are easier to eat. By controlling the thickness of the slices, you prevent your guest from cutting off more than he or she can comfortably chew. The meat will also seem more tender, regardless of the temperature to which it was cooked.

• Don’t be afraid to cut a steak before you cook it. The kabob experiment taught me that. Also, the 4-by-4-inch blocks used in the test were trimmed of most of their perimeter fat, and that prevented flare-ups.

HAMBURGER SUCCESS

There are six or seven ground meat options, not counting pork, lamb, and veal. Successful meat cookery depends on knowing the nature of the cut. Ground round and ground sirloin come from the round and sirloin primals, respectively. They’re lean and, if cooked to recommended hamburger temperature, will be overcooked and dry. Chuck comes from the chuck primal. It has a bit of connective tissue and contains about 30 percent fat. When ground, chuck is exceptional for hamburger making. Hamburger or ground beef is made from leftover meat trimmings. That’s likely to include filet and rib—good stuff. So when buying hamburger or ground beef, it’s likely to be better than buying ground round.