I'm Just Here for the Food (5 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Iron

is dense—really dense—which makes it a relatively slow conductor. But that density also allows for even heating, and once it gets hot it stays hot.

7

Iron is very economical, and cooking with it supplies dietary iron, which a lot of us (especially women) tend to run short on. Cast-iron pans must occasionally be seasoned, or cured, with a thin layer of hot fat in order to seal the surface against rust (see Cast Iron Feeding Instructions). Some folks sneer at the maintenance required, but considering that ours is the very culture that nurtured Sea Monkeys, Chia Pets, and Pet Rocks, taking care of an iron skillet shouldn’t be a problem.

THE MAKING OF CAST IRON

To cast iron, a pattern is made (a positive image of a pan, pot, or what have you). Then a mixture of sand and clay is packed around it under high pressure creating a mold, or cake. Molten iron is poured through a small opening in the cake. After the iron has solidified, the cake is broken open, revealing the newborn cookware. The sand is then broken up and reused.

CAST IRON FEEDING INSTRUCTIONS

1.

Place the pan to be cured on the top rack of a cold oven and place a sheet pan or baking sheet on the bottom rack.

2.

Turn the heat to 350° F.

3.

When the pan is warm but still touchable, remove the pan and spoon in a dollop of solid vegetable shortening, which is more refined than other oils and won’t leave a nasty film. As the shortening melts, use a paper towel to smear the fat all over the pan, inside, outside, handle—everywhere.

4.

Place the pan back in the oven, upside down. This prevents excess fat from pooling in the bottom and botching the cure.

5.

Bake for 1 hour, then kill the heat and let the pan cool for a few minutes. (Use fireproof gloves when you remove the pan from the oven.)

6.

Wipe the pan clean but don’t wash it until after you’ve used it.

That’s it. To clean a cast-iron pan, I usually add a little fat to the still-hot pan, toss in some kosher salt, and rub it with paper towels. If that doesn’t do the trick, I’ll wash it with mild detergent, warm water, and a sponge. I re-cure my cast-iron pans every New Year’s Day, whether I need to or not.

ADDITIONAL SEAR GEAR

Spray bottle

Your standard buck-fifty drugstore pump bottle is the perfect tool for applying a thin coat of lubricant (cooking oil) to the surface of the food to be seared. Beware of fancy-looking mister bottles. I’ve had three and worn out three with only moderate use.

Spring-loaded tongs

A pair of these is like having a big metal hand. Muzzle with a rubber band for low-profile storage. I keep a short pair for the kitchen and a long pair for the grill.

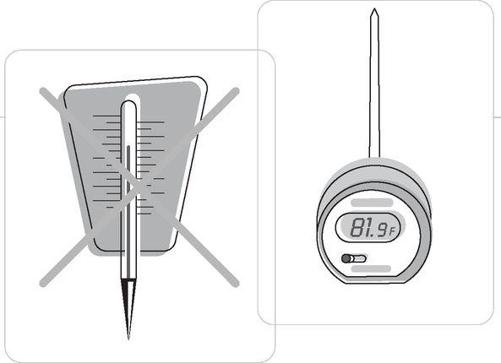

Instant-read thermometer

Heat control is the cook’s primary directive, and yet there are a lot of cooks out there who do not own this simple device. This is like riding a motorcycle without a helmet, or owning a pit bull but not homeowner’s insurance, or working a government job without a shredder. It’s crazy. I’m not talking about the old metal-tipped glass tube with the metal paddle on it that you could have tapped a maple tree with. I am talking about a slender metal probe topped with a digital readout of some type. Analog models are also available, but they’re easily swayed out of concentration, so use them at your own risk.

Welding gloves

Potholders are for sissies and mitts are for baseball. If I’m gonna grab a five hundred-degree pan, I want protection that reaches halfway to my elbow. Skip the kitchen shop and head to the hardware store.

Splatter guard

As the pan gets hot it’s going to turn into a radiator. The air around it is going to get hot, expand, and rise, taking microscopic drops of grease with it. If you’ve got a really strong ventilation hood, these drops may get caught up in the draft and get on out of the house. Odds are, though, the air is simply going to cool down as it rises, allowing the particles to fall down onto any horizontal surface they can find. The best way to prevent this is by using a splatter guard. It’s basically a screen door for your pan.

Make sure you buy one wide enough to cover your widest sauté pan, because you definitely don’t want to pan fry without this device in place. Besides preventing clean-up nightmares, it’s also your own best protection against flying grease. (Don’t think this is an issue? Try frying bacon naked sometime.)

Fresh air

Any time you get animal protein around very high heat there’s going to be some smoke. How much depends on the fat content of the meat. So turn your exhaust fan on, and if you don’t have one, open a window and maybe a door. If for some reason you have a smoke detector right over the cook top (though I can’t imagine why you would), take the battery out until you’ve finished cooking.

REACTIVITY

When we talk about “reactive” metals these days, we’re talking about aluminum and maybe copper. Metals such as stainless steel are actually surrounded by a very thin layer (a few molecules thick, tops) of oxide that is created at the point where metal and air meet. Despite the fact that it’s technically gas, this film creates a formidable barrier between food and pan.

The film around aluminum is very vulnerable to acid. When acidic foods are cooked in aluminum, traces of the metal leech into the food. This is why every tomato sauce recipe written in English demands that we cook it in a “nonreactive” vessel. And although researchers haven’t been able to pin the cause of Alzheimer’s disease on aluminum despite years of trying, there does appear to be a relationship. Anodized aluminum appears to be safe. (Anodizing uses electricity to deposit an oxide film on a metal, thus rendering it nonreactive.) The film, however, can be scratched, which is why I just stay clear of aluminum cookware altogether. I do allow aluminum foil to come in direct contact with food, which some folks would argue is as bad as snorting the stuff uncut. Sorry, but aluminum foil is just too darned important a tool in my kitchen. I’ll give up antacid tablets and even deodorant first (both of which contain whopping doses of aluminum).

Copper is also reactive, but almost all copper cookware is lined with tin (which does have to be replaced every now and then). A century ago, when pennies were 100-percent copper, it was a common practice to drop one in a pot of cabbage soup to keep it green (copper ions, you know). Copper ions also bring stability to egg foams, which is why I whip egg whites in a copper bowl. Of course, in very large amounts copper is even more toxic than aluminum. Life’s complicated.

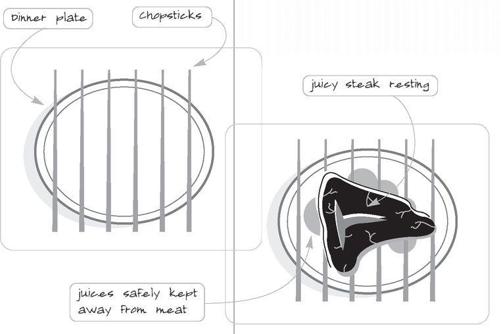

Wooden chopsticks

If you’re not going to rest your meat, you might as well not cook it. Make your own resting rack anywhere, anytime, with these amazing sticks! Take your average dinner plate. Place five or six chopsticks thusly:

Now you’ve got the perfect place to rest a wide variety of your favorite meats. You should, of course, keep them cozy under a loose layer of foil.

APPROPRIATE FOOD

Searing is unique in that it is not only used to cook food to doneness, but as an opening act for other cooking methods. Why? Because it’s the fastest way to get heat into food so it’s the fastest way to brown the surface of food. Brown is good. Brown works. Of course, if you wish to attain a delicious, golden brown crust you must choose your food wisely. To do so, it helps to understand the reaction responsible for browning.

Any carbon-based life form (and all food used to be alive at some point) will turn black if exposed to enough heat; in other words, it turns to charcoal. However, in order to brown, the food in question must contain high levels of either carbohydrates, which brown via caramelization, or proteins, which brown thanks to the chemical chaos that is the Maillard reaction (see below).

THE MAILLARD REACTION

When certain carbohydrates meet up with certain amino acids in the presence of high heat, dozens if not hundreds of new compounds are created. Some create flavor, others create color. Left to run amok, the Maillard reaction leads directly to the condition commonly known as “burned,” which has its own flavors and colors—none of which are good.

So we need a food containing amino acids and carbs. And since we want to get this crust on as much of the food as possible, a food with a flat surface would be helpful, especially if you intend to sear it until it’s cooked to completion. What we need is meat.

But it should be the right kind of meat. Some cuts of meat are quite tough and require prolonged cooking in order to break down connective tissues. Stew meat, lamb shanks, and chuck roast, for example, can be seared to add that “browned” flavor, but then should be slowly braised or simmered until done.

BIG RED BOOKO’ BLUE

I like filet of tenderloin steak as much as the next guy. A good one is at least 1

½

-inches thick, though, and if you try to sear it to doneness (meaning medium-rare, of course) the outside will look and taste like a meteorite.

The solution: butterfly it. Lay out the meat and find the edge that’s kind of flat. Pick up your boning knife and turn the steak so that the flat side is facing away from the knife. Carefully slice the steak horizontally through the center, cutting through to the flat edge. Then open it like a book.

Liberally season the steak and sear one side. Flip and repeat. Now just look at what you’ve done. You’ve doubled the flavor by doubling the seared surface area (and how about adding a bit of blue cheese in the center, too?)

THE TROUBLE WITH SEARING

Doneness is a big issue. If the meat is thin enough, by the time the first side has earned its golden crust the interior will have cooked halfway through, so you flip. By the time the second side reaches maximum crustage (a minute or two longer than it took the first side, since the pan isn’t as hot) you should have a perfectly cooked piece of meat.

However, the great majority of the meats that present themselves to the cook are not the perfect shape or size and therefore will not be done on the inside by the time the outer surfaces have reached golden brown and delicious status. The way I see it, you’re left with three solid choices:

1. Change the thickness of the food.