I'm Just Here for the Food (3 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

What we can take from this is that although the heat is still moving via conduction, the convection rate is actually an equal if not greater consideration. This is why convection is usually considered as its own classification of heat transference. Here it is in slightly different terms.

Let’s say it’s an average Wednesday night in the early Stone Age and you, an average

Homo erectus

, return to your cave with a nice big mammoth steak. You could chew it up raw, or you could:

a. Build a fire and hang the hunk a foot or so over the flames. This would be cooking via convection. That means that the vapor (smoke) and the surrounding air will absorb the fire’s heat, expand, and rise upward. Since hot always moves to cold, part of this thermal energy moves into the meat. The faster the air/gasses move past the meat, the quicker it will cook.

THE LUCY MODEL 1

You place two pieces of food in a pot of water; one is big (Ethel, on the left), one is small (Lucy, on the right). The temperature of the water (a measurement of its heat content) is represented by the number of candies on the conveyor belt. The speed of the conveyor belt represents convection—that is, the number of heat units (or candies) being brought in contact with the food (Ethel and Lucy) via movement of the medium, in this case water molecules. Time is, of course, time.

THE LUCY MODEL 2

Let’s say the water is set in motion (convection) by being heated to 195° F (technically a simmer). Ethel and Lucy start suckin’ in the heat, but since the convection rate is relatively slow, they don’t fill up very fast.

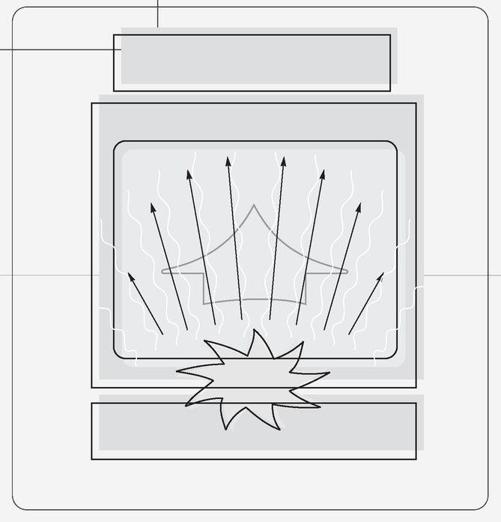

b. Build a fire and allow it to die down to a bed of brightly glowing coals, then hang the meat next to but not above the coals. Now radiation is solely responsible for broiling the steak. (Unlike convection currents, which rely on the fact that heat rises, radiant energy moves equally well in all directions, which explains why food cooks under a broiler.)

c. Build a fire and set a flat rock next to or over it. After an hour or so, slap the meat on the hot rock. That’s cooking via conduction.

4

THE LUCY MODEL 2 (CONTINUED)

Now if the water were 17° F higher, it would be boiling. That would mean a few more heat units on the old conveyor, sure, but more important, the water would be moving (convection) much faster, thus delivering more heat in less time. (Beyond the convection of the water itself, boiling water has additional movement due to the bubbles traveling upward from countless points on the bottom of the vessel). So, now you’ve got the same amount of heat moving into the foods in much less time. This seems like it would be a good idea, right? Well, that depends on the food.

THE LUCY MODEL 3

Let’s say that in 5 minutes both Lucy and Ethel consume 20 candies apiece. Lucy’s feeling a little full, but since Ethel has far more mass, she’s not even warmed up yet. Eventually Ethel will be done, but by that time Lucy will be toast—that is, overcooked.

THE DESERT AS OVEN

Radiant energy heats the rocks and the desert floor as well as the air itself which expands and rises in a natural convection. This rising current of air explains why birds can seem to float in the same space for hours without flapping their wings. They’re riding thermals. If there’s enough moisture around, these thermals will eventually build thunderheads.

Of course methods may be combined and hybridized. If you hung that meat directly over glowing coals, you’d be cooking with both radiant energy and convection. If you were advanced enough to have a vessel in which to boil water, you could drop your meat in and cook it by conduction and, since the water would be moving, convection as well.

In today’s kitchen, most cooking is from hybrid methods:

Addito Salis Grano

5

Given the surfeit of flavoring agents available to the twenty-first century cook, the inclusion of salt in Baron von Rumohr’s big-three list (along with water and heat) may seem quaint. But if you polled half of the world’s chefs, I bet one in three would say that knowing how to handle salt is at the heart of cooking. Without it, you’re dead.

What’s so magical about NaCl, the only rock we eat? From whence does it get its power? Simple. Not only does it taste good, it makes just about everything it comes in contact with taste good. Not salty, but better.

What’s even more interesting is that without salt’s crystalline blessing even dry-aged Kobe beef grilled to medium-rare perfection would taste like a communion wafer. Sodium naysayers will tell you that the taste for salt has been programmed into us by the dark agents of industry. I think it was programmed into us by God. Why else would our tongues have receptors exclusively reserved for its recognition?

IRONY PART I

In an attempt to be fashionably healthy, you forswear all salt and adopt a twenty-five-cup-a-day water habit. You pour the wet stuff in so fast and furious that after a few days your cells become slightly flooded, diluting your electrolytes (the power workers of the body). This results in a slowing of neural transmissions. Your spatial judgment becomes impaired, as do your balance and reflexes. So instead of stepping over that cigar butt, you trip over it, falling off the train platform in front of the oncoming uptown express. And all because you didn’t eat your salt. Shame on you.

IRONY PART II

You’re in the middle of the ocean in a raft. You have no water supply with you so you take a nice long drink of seawater. Soon you find you’re thirsty again so you drink more . . . and more. Trouble is, seawater is just salty enough that you can never quite get enough water to flush the excess salt. Your cells, desperate to balance osmotic pressure, dump water until they shrivel and parch. Your heart turns into a spastic drum machine and your nervous system freaks as your kidneys lose their dictatorlike grasp on your body chemistry. Tomorrow you’re raving mad. The day after that you’re dead. Shame on you.

Think I’m whacked? Try to explain this: On average, Japanese people consume twice as much salt as Americans yet they have the gall to live an average of ten years longer.

6

Now, despite the fact that the 1970s tied salt to the stake, the 80s stacked the wood, and the 90s lit the match, the guys in the white lab coats have finally gotten hip to what the guys in the white kitchen coats have known all along: salt is good . . . salt works. In fact, a healthy adult can pretty much put salt out of his or her mind as long as he or she (a) has two functioning kidneys; and (b) drinks plenty of water.