In Maremma (13 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

The asp was more than a meter long. After we dispatched it, Ilvo invited us over to his house for a grappa. He told us that once, many years ago, he had encountered a pregnant viper on his doorstep. No sooner had he killed it with his pitchfork than it burst open and thirteen

cuccioli

(babies) writhed out. Viper

cuccioli

are so venomous, Ilvo went on, that their mothers, in order to avoid being done in by their offspring during labor,

climbed into the trees and quite literally dropped them onto the ground or onto the heads of unlucky passersby. This was why you had to be sure to wear a hat when you took a walk in the woods.

cuccioli

(babies) writhed out. Viper

cuccioli

are so venomous, Ilvo went on, that their mothers, in order to avoid being done in by their offspring during labor,

climbed into the trees and quite literally dropped them onto the ground or onto the heads of unlucky passersby. This was why you had to be sure to wear a hat when you took a walk in the woods.

One windy June afternoon when we were still living in Rome, we were walking through the Forum when we found ourselves being rained upon bywhite myrtle flowers. Another afternoon in the Forum, during the winter, we had seen half of a smallbronze-colored serpent twisting furiously upon the ground. There was something in both happenings that evoked Ovid's

Metamorphoses.

Was the serpent from the union of the copulating snakes that transformed Tiresias into a woman? Were the myrtle flowers transformed lovers' tears?

Metamorphoses.

Was the serpent from the union of the copulating snakes that transformed Tiresias into a woman? Were the myrtle flowers transformed lovers' tears?

22

T

OLO WAS BORN in Scansanoâin Maremmaâon August 18, 1997, and spent the formative first months of his life in Rome. Notwithstanding his having an English father, Champion Harrowhill Hunter's Moon, he was an Italian dog. There just were three puppies in his litter (his mother's first)âtwo males and one female. Tolo's brother died shortly after being born.

OLO WAS BORN in Scansanoâin Maremmaâon August 18, 1997, and spent the formative first months of his life in Rome. Notwithstanding his having an English father, Champion Harrowhill Hunter's Moon, he was an Italian dog. There just were three puppies in his litter (his mother's first)âtwo males and one female. Tolo's brother died shortly after being born.

If we had not been about to move to Maremma, we would not have felt that it was right for Tolo to come live with usâwhich he did on November 29, 1997. A fox terrier deserves better than life in an apartment. These dogs need scope. From

The New York Times

(February 9,1908):

The New York Times

(February 9,1908):

Inspired by the recent attempt of robbers to effect an entrance to the famous Apollo Gallery of the Louvre Museum, the Directors of that institution have decided to follow the example of the Paris police and organize a special corps of trained watch dogs... “We shall, in all probability, use fox terriers for the purpose” [said M. Homolle, Director of the National Museums], “as they seem to be the most alert and sagacious.”

For the first few months of his life, however, life in the

caput mundi

was okay with Tolo. There he learned to be

a cane signorile.

caput mundi

was okay with Tolo. There he learned to be

a cane signorile.

Â

Tolo in Maremma: La Caccia

(Photo by MM)

(Photo by MM)

Once we settled in the country, Tolo became the doggiest dog in the worldâpatrolling the olive grove, chasing wild cats up trees, barking at the sheep, fighting with weasels, murdering hedgehogs, following the shadows of butterflies across the lawn. When he was about a year old, he disappeared. We drove along every road for kilometers looking for him, called neighbors asking them to be on the qui

vive,

and prayed. Our greatest fear was that he had been poisoned: people who own sheep, in order to protect them from the predations of wolves, will put out meat laced with poison. Many blameless dogs have died from getting to this meat before the wolves. A couple of days later, one of the neighbors did call: Tolo was at his house, along with a gang of other male dogs,

since there was a female Maremmana sheepdog in heat. The next morning, we took Tolo to Marco, one of the veterinarians in Semproniano, to be castrated.

vive,

and prayed. Our greatest fear was that he had been poisoned: people who own sheep, in order to protect them from the predations of wolves, will put out meat laced with poison. Many blameless dogs have died from getting to this meat before the wolves. A couple of days later, one of the neighbors did call: Tolo was at his house, along with a gang of other male dogs,

since there was a female Maremmana sheepdog in heat. The next morning, we took Tolo to Marco, one of the veterinarians in Semproniano, to be castrated.

He was a perfect traveller and a welcome guest at places where many people were not. Among the hotels at which he stayed were the Principe di Savioa in Milan, the Villa d'Este in Cernobbio, and the Villa Cipriani in Asolo. Sometimes meals were delivered to him by room service at the hotel's initiativeâa

cotoletta milanese

or

fegato alla veneziana.

He went to Vienna and to the South of France, to Amsterdam and Brussels, and to America.

cotoletta milanese

or

fegato alla veneziana.

He went to Vienna and to the South of France, to Amsterdam and Brussels, and to America.

What Christopher Hibbert wrote of King Edward VII's fox terrier, Caesar, could be written of Tolo:

Despite the ministrations of the footman whose duty it was to wash and comb him, Caesar ... was often to be seen with his mouth covered with prickles after an unsuccessful tussle with a hedgehog. The King loved him dearly, took him abroad, and allowed him to sleep in an easy chair by his bed ... He could never bring himself to smack the dog, however reprehensible his behavior; and “it was a picture,” so Stamper, the motor engineer, said, “to see the King standing shaking his stick at the dog when he had done wrong. âYou naughty dog,' he would say very slowly. âYou naughty, naughty dog.' And Caesar would wag his tail and âsmile' cheerfully into his master's eyes, until his Majesty smiled back in spite of himself.” Devoted as he was to the King, though, Caesar showed not the least interest in the advances of other human beings who

bent down to fondle him, disdaining to notice the staff when he accompanied the King on an inspection ...

bent down to fondle him, disdaining to notice the staff when he accompanied the King on an inspection ...

Tolo was happy in Maremmaâin many ways happier than we were. He took his days and his dreams as a birthright.

23

Trama di Maggio, olio per assagio.

Trama di Giugno, olio per lavarsi il grugno.

Trama di Giugno, olio per lavarsi il grugno.

Â

Olive blooms in May, oil just to taste.

Olive blooms in June, oil to wash your face.

Olive blooms in June, oil to wash your face.

OF THE MANY agricultural rituals that defined the Maremman yearâthe cutting of the hay in May, the threshing of the wheat in July, the

vendemmia

(grape harvest) in the autumnânone meant more than the November pressing of the olives. Oil, after all, is the foundation of Maremman life; unlike their cousins to the north, the people here almost never usedâindeed, barely comprehendedâbutter, which no doubt contributed to their famous longevity. (Rosaria told us that heart disease was almost unknown in Semproniano.) Nor did the making of the oil lack its element of pageantry. When the young oil arrived, the people of Semproniano would greet it with the sort of exuberance that the French saveâinexplicablyâfor Beaujolais nouveau. Because it had such a peppery kick, the new oil was never used for cooking but instead drizzled over a salad or a bowl of

zuppa

di

ceci.

The best way to serve the new oil, however, was to pour some onto a

piece of grilled, unsalted bread that had been rubbed with garlic: this was the famed bruschetta, so commonly imitated and so rarely gotten right, even in Tuscany. For bruschetta must be subtle, which is the point so many restaurateurs miss. The fact that the Florentine version is known as

fett'unta

â“greasy slice”âattests to its comparative coarseness.

vendemmia

(grape harvest) in the autumnânone meant more than the November pressing of the olives. Oil, after all, is the foundation of Maremman life; unlike their cousins to the north, the people here almost never usedâindeed, barely comprehendedâbutter, which no doubt contributed to their famous longevity. (Rosaria told us that heart disease was almost unknown in Semproniano.) Nor did the making of the oil lack its element of pageantry. When the young oil arrived, the people of Semproniano would greet it with the sort of exuberance that the French saveâinexplicablyâfor Beaujolais nouveau. Because it had such a peppery kick, the new oil was never used for cooking but instead drizzled over a salad or a bowl of

zuppa

di

ceci.

The best way to serve the new oil, however, was to pour some onto a

piece of grilled, unsalted bread that had been rubbed with garlic: this was the famed bruschetta, so commonly imitated and so rarely gotten right, even in Tuscany. For bruschetta must be subtle, which is the point so many restaurateurs miss. The fact that the Florentine version is known as

fett'unta

â“greasy slice”âattests to its comparative coarseness.

For a long time, Semproniano had one tourist attraction, the Olivone, an immense olive tree more than two thousand years old. Before Podere Fiume was finished, we visited the Olivone twice, sitting each time for a few moments under its capacious and maternal limbs.

We spoke of how, when we lived here, we would bring all our friends to see it. Then on May 10, 1998âthe evening of American Mother's Dayâsomeone torched the Olivone, burning it to the ground. The town went into mourning. In particular the children, who had a tradition of walking to the Olivone for a picnic on the last day of school, grieved the tree's passing. Ettore, Sauro's nine-year-old son, asked if he could borrow one of our computers to write an essay called “The Olivone, Burned and No More.” For months afterwards, every time we ate at Il Mulino, Martino urged us to write a book about the Olivone. (The arsonist, alas, was never arrested, though his identity is known.)

In Italy, politics often matter on a local level far more deeply than they do nationally. Almost immediately after the Olivone burned, dark rumors began to spread that one or another of the two political parties vying for control of the town (it was an election year) had been responsible for this barbarous and selfish act. As it happened, the mayor, who had won the previous election by one vote, was a member of the far right

Alleanza Nazionale. One afternoon (Friday, November 13, 1998), to our great surprise, he knocked at our door and introduced himself. For about ten minutes he outlined his plans for the coming year: the new library to which he hoped we might donate some books, the new sports ground, the roads he was going to have paved (ours included). Apparently he didn't realize that while we were residents of Semproniano, we were not Italian citizens and therefore could not vote. Afterwards, rather delighted by his visit (there is always something grand about a mayor), we walked over to tell Delia and Ilvo that he had been by to see us. (He had

not

been by to see them.) “

Fascistone,”

Delia said. As we soon learned, they, like all our friends here, were lifelong Communists, and were worried lest the mayor, with promises of paving, should lure us to his side.

Alleanza Nazionale. One afternoon (Friday, November 13, 1998), to our great surprise, he knocked at our door and introduced himself. For about ten minutes he outlined his plans for the coming year: the new library to which he hoped we might donate some books, the new sports ground, the roads he was going to have paved (ours included). Apparently he didn't realize that while we were residents of Semproniano, we were not Italian citizens and therefore could not vote. Afterwards, rather delighted by his visit (there is always something grand about a mayor), we walked over to tell Delia and Ilvo that he had been by to see us. (He had

not

been by to see them.) “

Fascistone,”

Delia said. As we soon learned, they, like all our friends here, were lifelong Communists, and were worried lest the mayor, with promises of paving, should lure us to his side.

Â

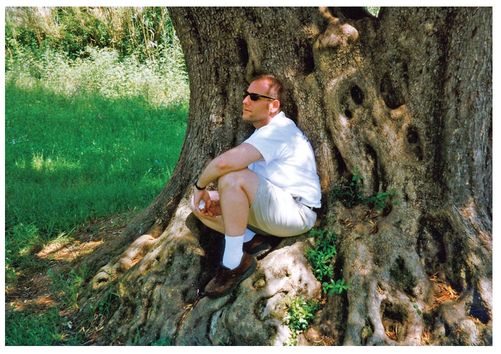

DL at the Olivone

(Photo by MM)

(Photo by MM)

In the end the mayor won the electionâby far more than one vote. Our friends said that he had done so by spreading lies throughout the countryside, telling the farmers that if they voted for the Communists, the

ambientalisti

(environmentalists) would set wolves loose to kill their sheep. Then the whole area could be made over into a preserve. Some hinted that it was in order to head off such a transformation that the Olivone was burnedâa scenario we thought paranoid at the time, but that now seems highly probable.

ambientalisti

(environmentalists) would set wolves loose to kill their sheep. Then the whole area could be made over into a preserve. Some hinted that it was in order to head off such a transformation that the Olivone was burnedâa scenario we thought paranoid at the time, but that now seems highly probable.

Â

Oliveto, Podere Fiume

(Photo by MM)

(Photo by MM)

To Ilvo and Delia, the burning of a two-thousand-year-old olive tree was murder. In a town where oil was life, this great mother of a tree was looked to not only as a source of sustenance but a force of good. When Pina offered us oil made from the olives of the Olivone, we accepted it with an almost mystic wonderment, not because the oil tasted any different from any other local oil but because it came from the Olivone, which was born before Christ.

Afterwards we tried to console ourselves with the knowledge that each of our own trees, though mere striplings, had the potential to grow into an Olivone. We had thirty-eight, which was just enough to produce a year's worth of oil for two hungry people and a dog.

Other books

Soul of Kandrith (The Kandrith Series) by Luiken, Nicole

The Poison Diaries: Nightshade by Maryrose Wood

The Seventh Day by Joy Dettman

XXX - 136 Office Slave by J. W. McKenna

La forja de un rebelde by Arturo Barea

Predator's Refuge by Rosanna Leo

Danger in a Fur Coat (The Fur Coat Society Book 4) by Sloane Meyers

Where Mercy Is Shown, Mercy Is Given (2010) by Chapman, Duane Dog

Tenacious Trents 01 - A Misguided Lord by Jane Charles

i bc27f85be50b71b1 by Unknown