In Maremma (4 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

6

B

ECAUSE WE HAD been living for half a dozen years in furnished or semifurnished apartments when we bought Podere Fiume, the only furniture we owned was a cornflower-blue sofa and a pair of leather library chairs, which we intended to put in the living room; a desk with chesnut legs and a top of Ligurian

pietra serena;

a Bokara carpet; four neo-Gustavian chairs with unupholstered seats; and a bed. This is how we came to meet Olimpia Orsini.

ECAUSE WE HAD been living for half a dozen years in furnished or semifurnished apartments when we bought Podere Fiume, the only furniture we owned was a cornflower-blue sofa and a pair of leather library chairs, which we intended to put in the living room; a desk with chesnut legs and a top of Ligurian

pietra serena;

a Bokara carpet; four neo-Gustavian chairs with unupholstered seats; and a bed. This is how we came to meet Olimpia Orsini.

An interior designer of some repute in Rome, Olimpia also owned a little shop that she refused to call a shopâit was her “studio,” she insistedâon Via del Boschetto. (She referred to herself not as a “designer” but as an “interior,” which, considered together with the fact that she had taken a degree in psychology, was appropriate.) A few months after we met her, she transferred her shop to a small street just off Via Marguta, where some of the most expensive antique stores in Rome are located, and had business cards printed on which she gave her address as “Vicolo dell'Orto di Napoli (Via Marguta).” Such a street name must have seemed an augur of good things to Olimpia, who was from Naples. Her age was difficult to determineâanywhere between forty-five and sixty, we figured. She had long dark-blond hair, wore

Chanel suits in even the most inclement weather, and smoked incessantly.

Chanel suits in even the most inclement weather, and smoked incessantly.

After we moved to Podere Fiume, we asked Renato, the aristocracy-obsessed owner of the antique shop at the Terme di Saturnia, if he knew her. “The Countess Orsini?” he asked excitedly. The Orsinis, he reminded us, were a noble Tuscan family; an Orsini had built the fantastic and eerie statuary garden at Bomarzo; there was an Orsini stronghold not far from us, in Pitigliano.

To these Orsinis, Olimpia bore the same relation that Tess does to the dâUrbervilles: that is to say, none at all. In fact, Olimpia was not her real nameâit was Marilenaâand even this Elizabeth had discovered only because she had happened to glimpse her

carta d'identitÃ

one afternoon when it was lying on the desk of her shop. Her husband, Puccio, was a retired Alitalia pilotâ“the sort of man,” Domenico said, “who always has four or five million lire in his pocket”âand such was his devotion to Olimpia that, rather than relaxing in his retirement, he spent most of his time driving around Rome on a Vespa doing commissions for her. “Puccio,” she might instruct, “take these chairs over to Luigi's workshop.”

carta d'identitÃ

one afternoon when it was lying on the desk of her shop. Her husband, Puccio, was a retired Alitalia pilotâ“the sort of man,” Domenico said, “who always has four or five million lire in his pocket”âand such was his devotion to Olimpia that, rather than relaxing in his retirement, he spent most of his time driving around Rome on a Vespa doing commissions for her. “Puccio,” she might instruct, “take these chairs over to Luigi's workshop.”

“Si, bella

,” he would answer, strap a pair ofgilt-trimmed armchairs onto his Vespa, and zoom off. (They had a son in his early twenties whom we never saw. “I could never have a daughter,” Olimpia told us. “I like being the only hen in the coop.”)

,” he would answer, strap a pair ofgilt-trimmed armchairs onto his Vespa, and zoom off. (They had a son in his early twenties whom we never saw. “I could never have a daughter,” Olimpia told us. “I like being the only hen in the coop.”)

That Olimpia had wonderful, eclectic taste was indisputable. Her shop was always full of curious and unlikely pieces: Venetian mercury mirrors edged with seashells, bronze lamps with classical figures in high relief, chairs upon the legs of which mermen and mermaids

disported themselves, panels of antique wallpaper and toile de Jouy, a leopard skin with taxidermied head draped nonchalantly across the back of a

dormeuse

. Olimpia upholstered all the furniture in her shop in the plainest muslin. Nothing was dark, and no wood was wood-colored. Chairs that she brought into the shop in dreadful condition, grimy from years of neglect, she would “refresh” simply by stitching some thousand-lire-a-meter cotton on to the worn cushions and slapping the wood with white paint. In her fondness for white, if in no other regard, she echoed Gigliola. Both women echoed the famous English designer Syrie Maugham. (Olimpia's failure, however, to replace the old horsehair-and-straw stuffing in some of these chairs considerably distressed Luigi, the upholsterer, who considered them unhygienic.)

disported themselves, panels of antique wallpaper and toile de Jouy, a leopard skin with taxidermied head draped nonchalantly across the back of a

dormeuse

. Olimpia upholstered all the furniture in her shop in the plainest muslin. Nothing was dark, and no wood was wood-colored. Chairs that she brought into the shop in dreadful condition, grimy from years of neglect, she would “refresh” simply by stitching some thousand-lire-a-meter cotton on to the worn cushions and slapping the wood with white paint. In her fondness for white, if in no other regard, she echoed Gigliola. Both women echoed the famous English designer Syrie Maugham. (Olimpia's failure, however, to replace the old horsehair-and-straw stuffing in some of these chairs considerably distressed Luigi, the upholsterer, who considered them unhygienic.)

From Olimpia, we ended up buying a couple of side tables and a derelict but magnificent eighteenth-century carved-wood-and-gesso sofa from Venice, which had managed to escape the attentions of her paintbrush only by virtue of its extraordinary colorâthe most subtle of gray greens. We also bought a pair of white armchairs that were intended for the winter gardenâa room occupying an arcaded space where farm equipment was formerly stored. (These chairs were something of a wish fulfillment for MM, who, when being taught perspective in high school art class, had drawn, in one-point perspective, a chair in the very style of those we'd bought from Olimpia. Although the drawing was done in dark gray pencil, his mother helped him to frame it with a mat the color of one of the stripes of the fabric that covered the seat and back of the chair that had been his model.)

Unfortunately, their stuffing smelled, and Tolo displayed from the very beginning a great fondness for sleeping on them. We asked Olimpia if she would buy them back or, short of that, sell them on our behalf, which she did in four days.

Unfortunately, their stuffing smelled, and Tolo displayed from the very beginning a great fondness for sleeping on them. We asked Olimpia if she would buy them back or, short of that, sell them on our behalf, which she did in four days.

7

O

NE BLUSTERY AFTERNOON, Sauro came by to do some small work. When he arrived, we had a candle burning in a pewter candlestick on the mantel of the fireplace. Sauro looked at it quizzically.

NE BLUSTERY AFTERNOON, Sauro came by to do some small work. When he arrived, we had a candle burning in a pewter candlestick on the mantel of the fireplace. Sauro looked at it quizzically.

“A candle!” he said. “Did you have a power outage?”

“It's for atmosphere;” we answered. “It makes a nice light.”

With an affirmative “Hmm!” Sauro took his tools upstairs.

Atmosphereâthe sort embodied by a candle burning on a blustery afternoonâmeant less to him than it did to us. His own house was a far cry from the Italian country house of dreams, where worn armchairs and wooden footstools sat gathered around the immense fireplace that in dreams is always ablaze and crackling, giving the house a center around which to cohere. Podere Fiume, however, had no fireplace when we bought it. In the kitchen, which would later become DL's study there was only the little Zoppas wood-burning stove. Perhaps because he came from Bari and had been educated in California, Domenico understood our longing for the hearth that in English is paired with home. In his own house in Beverly Hills, he had put fireplaces not only in the living room and dining room, but also the kitchen and two of the bedrooms. “When we're there in the winter, it's so nice and toasty,” he said, taking as much pleasure in his command of American idioms as in the toastiness itself.

Â

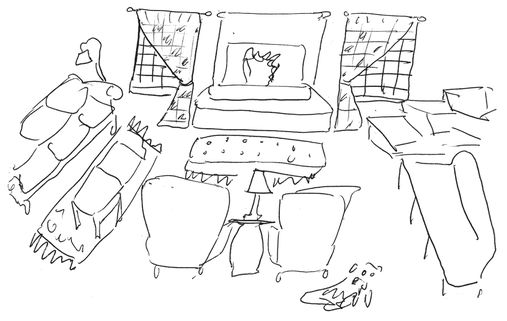

DL's drawingâmade after we bought Podere Fiume but before we began working on itâof how he wanted the living room to look. Except for the fireplace, this was what it looked like upon completion.

As it happens, there is a considerable market for antique fireplaces and fireplace tools in Italy. Even in big cities there are shops that deal exclusively in old

attrezzi:

wrought iron pokers; Renaissance andirons; enormous cast-iron plaques decorated with heraldic motifs or mythological figures, to be mounted on the back of the fireplace to throw heat forward; medieval hooks from which to hang the pots in which hundreds of years ago cooks prepared stews of meat and onion and

borlotti

(a variety of cranberry bean).

attrezzi:

wrought iron pokers; Renaissance andirons; enormous cast-iron plaques decorated with heraldic motifs or mythological figures, to be mounted on the back of the fireplace to throw heat forward; medieval hooks from which to hang the pots in which hundreds of years ago cooks prepared stews of meat and onion and

borlotti

(a variety of cranberry bean).

Our fireplace came from a man who salvaged them from villas in the Mugello, the mountains between Florence and Bologna. It was made of

pietra serena

and had the year of its making incised on one of its flanks: 1803.

It consisted of six pieces of stone: a mantel, a plinth that held up the mantel, and four side pieces to support the plinth. As a base (the poetic hearth), Sauro hauled in some enormous

sassi

(stones) that were the same color as the fireplace and that a friend of his had chiseled to make fit together. Once constructed, the fireplace measured a meter and a half by a bit more than a meter.

pietra serena

and had the year of its making incised on one of its flanks: 1803.

It consisted of six pieces of stone: a mantel, a plinth that held up the mantel, and four side pieces to support the plinth. As a base (the poetic hearth), Sauro hauled in some enormous

sassi

(stones) that were the same color as the fireplace and that a friend of his had chiseled to make fit together. Once constructed, the fireplace measured a meter and a half by a bit more than a meter.

Â

The Living Room, Podere Fiume

(Photo by Simon McBride)

(Photo by Simon McBride)

At this point it was midsummerâa blazing midsummer at thatâand hardly the moment to be building a fire. And so for a few months we filled the fireplace with old and patched copper cooking pots; dried wild artichokes; and even, for a few weeks, the television set; all the while waiting for the cold weather to come. (Country life knows its apogee in winter.) Already we had a complement of

attrezzi.

Between the house and the

uliveto,

a cord of wood was stacked. As a housewarming present, our friend Piero had even given us a pronged potato-roasting device designed to be fit into the embers.

attrezzi.

Between the house and the

uliveto,

a cord of wood was stacked. As a housewarming present, our friend Piero had even given us a pronged potato-roasting device designed to be fit into the embers.

In December, the time for fires came. We put logs into the embrace of the andirons; around their feet went the kindling. We lit a match and stood back. Fire! Smoke! Wasn't it supposed to be the other way around? We threw open the windows. Perhaps there was not enough wind outside to make the chimney draw. But the next dayâeven though there was more windâthe same thing happened.

Presently (December 16, 1998), Domenico drove up from Rome with Magini to meet with Sauro and assess the situation. After conferring among themselves for quite a while, they built a fire. This time a beautiful blaze leapt, the smoke following orders and going exactly where it was supposed to. Domenico gloated, just a littleâand a little too soon, for just then the smoke turned around and billowed into the room.

The problem, Domenico concluded, was quite simply that the opening was too big for the room. Why had he not considered this possibility

before

the fireplace was put in? “A fireplace like that, you need a chimney that's twice as high,” Sauro saidâwhy had he not said this while building it?âand proposed to install an electric fan that looked like a serrated chef's toque at the top of the chimney. But no, Domenico said, the solution was just to make the opening smaller, perhaps by attaching a large panel of copper or wood to the back side of the mantel. But no, Magini said, the solution was to drape a curtain over the fireplace, far enough away from the fire, of course, so that it wouldn't ignite!

before

the fireplace was put in? “A fireplace like that, you need a chimney that's twice as high,” Sauro saidâwhy had he not said this while building it?âand proposed to install an electric fan that looked like a serrated chef's toque at the top of the chimney. But no, Domenico said, the solution was just to make the opening smaller, perhaps by attaching a large panel of copper or wood to the back side of the mantel. But no, Magini said, the solution was to drape a curtain over the fireplace, far enough away from the fire, of course, so that it wouldn't ignite!

As far as we were concerned, none of the proposals on offer was going to do. By chance, however, DL had come across an article about a Danish company called

Morsø that made wood-burning stoves. In the illustration accompanying the article, one of these stovesâblack cast iron and with an image of a squirrel embossed on its sideâhad been placed inside a big fireplace very much like our own. When we told Domenico what we were considering, he cried, “How can you do that?” as if the mere idea of a stove injured him personally. “A country house without a fireplace . . . that would be terrible! I couldn't imagine my house in winter without a fire going!” We reminded him that in the case of his own house, he was seldom there in the cold months. We, on the other hand, had the whole winter before us, and could hardly spend it in a haze of wood smoke, our throats sore, our eyes burning, the furniture becoming sooty. “But that doesn't mean you should do something drastic,” he said. “We just have to study the problem . . . ” (In Italy, as everywhere, “study the problem” is synonymous with “put off the solution.”)

Morsø that made wood-burning stoves. In the illustration accompanying the article, one of these stovesâblack cast iron and with an image of a squirrel embossed on its sideâhad been placed inside a big fireplace very much like our own. When we told Domenico what we were considering, he cried, “How can you do that?” as if the mere idea of a stove injured him personally. “A country house without a fireplace . . . that would be terrible! I couldn't imagine my house in winter without a fire going!” We reminded him that in the case of his own house, he was seldom there in the cold months. We, on the other hand, had the whole winter before us, and could hardly spend it in a haze of wood smoke, our throats sore, our eyes burning, the furniture becoming sooty. “But that doesn't mean you should do something drastic,” he said. “We just have to study the problem . . . ” (In Italy, as everywhere, “study the problem” is synonymous with “put off the solution.”)

It was apparent that we had to take matters into our own hands. We found a dealer in wood-burning stoves in Grosseto. His shop was full of immense high-tech models, all gleaming chrome and superb efficiency. Mostly he dealt in the sort of small stoves that Sauro, Ilvo, and Delia kept in their kitchens, and in the summer he sold pizza ovens. Nonetheless we asked him about Morsø.

“Quello col scoiattolo

!

”

(“The one with the squirrel!”) he said, his eyes lighting up like those of the chef at a Chinese restaurant when, to his delight, a customer asks for crispy duck with taro root instead of chow mein. Not only did he know it, the Morso distributor was a friend of his. If we wanted, he could have the stove for us in three days.

“Quello col scoiattolo

!

”

(“The one with the squirrel!”) he said, his eyes lighting up like those of the chef at a Chinese restaurant when, to his delight, a customer asks for crispy duck with taro root instead of chow mein. Not only did he know it, the Morso distributor was a friend of his. If we wanted, he could have the stove for us in three days.

The stove fit perfectly inside the fireplace. Piero's little device for roasting potatoes went into a drawer somewhere. Something had to be sacrificed.

“A smaller wood-burning stove in the fireplace opening is the owners' choice for an easy and economical way to heat the room,” Elizabeth wrote in her book.

Â

Fire on a November Afternoon, Podere Fiume

(Photo by MM)

(Photo by MM)

Other books

The Vampire With the Dragon Tattoo (Love at Stake) by Sparks, Kerrelyn

Jane Bonander by Dancing on Snowflakes

Murder in LaMut by Raymond E. Feist, Joel Rosenberg

Husband and Wives by Susan Rogers Cooper

Lumbersexual (Novella) by Leslie McAdam

REGENCY: Loved by the Duke (Historical Billionaire Military Romance) (19th Century Victorian Short Stories) by Tencia Winters, Serena Vale

Someone Like You by Emma Hillman

Tides of Light by Gregory Benford

Lover's Gold by Kat Martin