In Maremma (6 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

“Accidenti!”

Delia said, which basically means, “I'll be damned!” “Here we don't do that.” Delia had been to Rome perhaps half a dozen times.

Delia said, which basically means, “I'll be damned!” “Here we don't do that.” Delia had been to Rome perhaps half a dozen times.

Still, she was in her own way worldly and shrewd. There was not much in world politics that escaped her ken. Thus when the wife of the Yugoslav president, Slobodan Milosevic, appeared on her kitchen television one morning (this was in the middle of the war in

Kosovo), she remarked, “I don't like that woman. She looks mad.” An editorial in that morning's

International Herald Tribune

had said the same thing.

Kosovo), she remarked, “I don't like that woman. She looks mad.” An editorial in that morning's

International Herald Tribune

had said the same thing.

Delia also had strong opinions about local politics. It was to her that we turned when something of a local nature perplexed or maddened us: for instance, the mosquitoes so tiny they could actually fit through the holes in our window screens. “What are they?” we asked. “How long will they last?”

“Oh, the little onesâ

piccini piccini?

We call them

cugini.”

piccini piccini?

We call them

cugini.”

Ilvo smiled. “Now you see what we really think of our cousins;” he said.

11

S

OMETIMES IN THE morning, on the way to Semproniano, we'd encounter a sheep jam. They had a way of appearing when you least expected them, and in the most inconvenient of places: on the other side of a harrowing hairpin turn, say, or on a bridge. We'd hit the brakes. Tolo, agitated by the rich odor of manure and urine, the music of bleats and

baas,

would start to bark madly, then try to dig his way through the back window. Meanwhile we'd idle. What else can you do when faced with a flock of forty ewes and a ram or two, their backs draped with coils of yellowing wool, like dreadlocks? Sometimes the sheep were alone; more often someone was leading themâan elderly farmer driving an equally elderly three-wheeled Ape (bee) or a woman on a Vespa (wasp). With a smile the shepherd or shepherdess would signal us forwardânot to drive around but

into

the herd.

OMETIMES IN THE morning, on the way to Semproniano, we'd encounter a sheep jam. They had a way of appearing when you least expected them, and in the most inconvenient of places: on the other side of a harrowing hairpin turn, say, or on a bridge. We'd hit the brakes. Tolo, agitated by the rich odor of manure and urine, the music of bleats and

baas,

would start to bark madly, then try to dig his way through the back window. Meanwhile we'd idle. What else can you do when faced with a flock of forty ewes and a ram or two, their backs draped with coils of yellowing wool, like dreadlocks? Sometimes the sheep were alone; more often someone was leading themâan elderly farmer driving an equally elderly three-wheeled Ape (bee) or a woman on a Vespa (wasp). With a smile the shepherd or shepherdess would signal us forwardânot to drive around but

into

the herd.

The first time we did this, it seemed no less weird than dangerous. With every centimeter we'd move forward, we'd anticipate the moment when the car would touch the sheep, lambs' legs would flatten under the wheels, wool would fly. And yet, at the crucial instant, the flock always did part, as the Red Sea parted for Moses.

That was what passed for traffic there, in that valley where not a stoplight was to be found for miles and miles in any direction.

12

W

HEN WE NEEDED or longed for “the city,” we went to Florence. Although Semproniano and Manciano were not far apart, people from Semproniano tended to regard Florence as their city while people from Manciano tended to regard Rome as theirs. Only once or twice during the years we lived in the country did we go to Florence for more than the day.

HEN WE NEEDED or longed for “the city,” we went to Florence. Although Semproniano and Manciano were not far apart, people from Semproniano tended to regard Florence as their city while people from Manciano tended to regard Rome as theirs. Only once or twice during the years we lived in the country did we go to Florence for more than the day.

The drive, via Scansano, Grosseto, Siena, and Poggi-bonsi (the skyline of San Gimignano in the distance), took close to three hours, so we always left before dawn; before the Bar Sport was open. This meant we usually had our first coffee somewhere on the outskirts of Siena. If Tolo was with usâSigner Pepe, his groomer, was in Florenceâwe'd get a plain croissant for him. (He would have liked to have had a caffe latte, too.) From there it was just an hour to Florence.

Returning to a place where you have lived is faintly troubling, no matter how attached to it you are. We'd begin at Robiglio on Via dei Servi, where one found the best coffee and pastries in Florence. The

baristi

were named Marco and Marco. Duly fortified, we'd split up and do what we'd come to do: go to the bank (the wife of the director of which owned the apartment we had rented on Via dei Neri); go to the library of the British

Institute to do research for whatever projects we were working on at the time; get our hair cut; look around in bookstores (the Paperback Exchange and the Libreria Internazionale Seeber and Feltrinelli) and music shops; buy Corn Flakes at Pegna and boxer shorts at the men's shop in the building where we had lived; maybe meet for lunch at Yellow Bar on Via Proconsolo, where the actor who played the carriage driver in the

film A Room with a View

often had lunchâor, if we were meeting friends either from the city or out of town, at Coco Lezzone, famous for its

farfalle con piselli and arista di maiale

(roast pork stuffed with rosemary and whole cloves of garlic) and, it was said, for being Prince Charles's favorite restaurant in Florence; and if it was winter, before leaving, we might have a hot chocolate with whipped cream at Rivoire on Piazza della Signoriaâto fortify us for the drive home.

baristi

were named Marco and Marco. Duly fortified, we'd split up and do what we'd come to do: go to the bank (the wife of the director of which owned the apartment we had rented on Via dei Neri); go to the library of the British

Institute to do research for whatever projects we were working on at the time; get our hair cut; look around in bookstores (the Paperback Exchange and the Libreria Internazionale Seeber and Feltrinelli) and music shops; buy Corn Flakes at Pegna and boxer shorts at the men's shop in the building where we had lived; maybe meet for lunch at Yellow Bar on Via Proconsolo, where the actor who played the carriage driver in the

film A Room with a View

often had lunchâor, if we were meeting friends either from the city or out of town, at Coco Lezzone, famous for its

farfalle con piselli and arista di maiale

(roast pork stuffed with rosemary and whole cloves of garlic) and, it was said, for being Prince Charles's favorite restaurant in Florence; and if it was winter, before leaving, we might have a hot chocolate with whipped cream at Rivoire on Piazza della Signoriaâto fortify us for the drive home.

13

I

N MARCH 2000, this article appeared in

Italy Daily,

a supplement to

The International Herald Tribune.

It says much about the poetry and madness of Italian bureaucracy:

N MARCH 2000, this article appeared in

Italy Daily,

a supplement to

The International Herald Tribune.

It says much about the poetry and madness of Italian bureaucracy:

Highway police arrested ten people late Wednesday in Pescara, charging them with running a fraudulent drivers' school that sold drivers' licenses for up to five million lire each. Another thirty-two people were accused of participating in what authorities described as a cooperative that drew clients from around Italy, some of whom were reportedly almost blind. Italians frequently complain that obtaining a drivers' license in Italy is difficult without attending costly schools. Foreign residents in Italy for more than one year are also expected to attend the schools and obtain a national license, regardless of their driving record.

For us, the long process of getting licenses began shortly after we bought Podere Fiume. To live in the country, one has to have a car, and to own a car in Italy,

one has to have an Italian

patente di guida

(driver's license). This is simply the law. (To own a car you also have to be a legal resident of Italy, which is attested by the issuing of a

carta d'identità ,

which requires you to have

a permesso di soggiorno

obtained from the

questura

of the province in which you wish to be resident, which requires you to have a visa, which you have to obtain in person from the Italian consular office closest to your official American residence: in DL's case Los Angeles, in MM's case Miami.) If you didn't have an Italian driver's license, your only options were either to ask an Italian friend to buy a car for you, then sign a document giving you the right to drive it, or to bring in a car from another countryâyet if you did this, after four months you would still be obliged to replace the foreign license plates with Italian ones, which required an Italian license.

one has to have an Italian

patente di guida

(driver's license). This is simply the law. (To own a car you also have to be a legal resident of Italy, which is attested by the issuing of a

carta d'identità ,

which requires you to have

a permesso di soggiorno

obtained from the

questura

of the province in which you wish to be resident, which requires you to have a visa, which you have to obtain in person from the Italian consular office closest to your official American residence: in DL's case Los Angeles, in MM's case Miami.) If you didn't have an Italian driver's license, your only options were either to ask an Italian friend to buy a car for you, then sign a document giving you the right to drive it, or to bring in a car from another countryâyet if you did this, after four months you would still be obliged to replace the foreign license plates with Italian ones, which required an Italian license.

Many countries have reciprocity agreements for licenses with Italy; the United States, unfortunately, is not one of them, since there is no federal driver's license, and it would be bureaucratically untenable for Italy to make separate agreements with each of the fifty states. As a result, even drivers who, like us, had had licenses for almost a quarter of a century were compelled to take the driving test. In Italian.

Wanting advice, we called Elizabeth, since we knew she had gotten an Italian license several years earlier. “Oh, it was easy,” she said. “I just paid someone to take the test for me.”

“But how can someone take it for you?”

“Only the oral part. What you do is you pretend you don't speak English and explain that you've brought along a translator. Of course he isn't really a translator.

You mumble to him, and he answers all the questions. It costs about two million lire.”

You mumble to him, and he answers all the questions. It costs about two million lire.”

Neither of us was particularly keen to pay two million lire to a “translator.” Nor did we believe that we needed one, even if Elizabeth had. After all, we both spoke Italian. We were good drivers.

A lawyer explained to us how we ought to proceed. Since obviously we didn't want to go to a driving school, we needed first to get in touch with an

agente.

An

agente

was basically someone who made his living mediating between bureaucracies and human beings. Little of a practical nature could be done here without one, since the system was so baroque that learning to negotiate even a small region of it required years of study.

agente.

An

agente

was basically someone who made his living mediating between bureaucracies and human beings. Little of a practical nature could be done here without one, since the system was so baroque that learning to negotiate even a small region of it required years of study.

The

agente

our friend recommended was named Bruno. He wore wraparound sunglasses and had a cashmere coat. To obtain licenses, he said, we would first have to complete a

pratica

(form). This would cost two hundred thousand lire. After that we would take an eye exam from a doctor who would then affirm that we were both in good health. This would cost one hundred and fifty thousand lire. After that, Bruno would make an appointment for us to take the

oral

exam. If we passed it, he would make an appointment for us to take the driving testâthe one behind the wheel.

agente

our friend recommended was named Bruno. He wore wraparound sunglasses and had a cashmere coat. To obtain licenses, he said, we would first have to complete a

pratica

(form). This would cost two hundred thousand lire. After that we would take an eye exam from a doctor who would then affirm that we were both in good health. This would cost one hundred and fifty thousand lire. After that, Bruno would make an appointment for us to take the

oral

exam. If we passed it, he would make an appointment for us to take the driving testâthe one behind the wheel.

Now the comedy began. First, we went to take the eye exam. The doctor who administered it turned out to be practically blind. (Perhaps he'd gotten his license in Pescara.) He could barely read our passports through his thick glasses or the clouds of smoke from his cigar. So far as we could tell, he was able to give the exam only because he had memorized the chart.

Once we received the necessary certificates, Bruno made an appointment for us to take the

teoria

âthe “theory” portion, given in the form of an oral exam. When? we asked. In a little more than two months, he told us. Two months! He shruggedâthere was a long waiting listâand added that in France the wait was usually

four

months. Then he gave us

foglie rose

(pink slips of paper) permitting us to drive during the interval. He also gave us a manual of road regulations to study, along with a book of sample written tests. These tests had a reputation forbeing almost sadistically difficult, mostly because they exalted the principle of the trick question. An example:

teoria

âthe “theory” portion, given in the form of an oral exam. When? we asked. In a little more than two months, he told us. Two months! He shruggedâthere was a long waiting listâand added that in France the wait was usually

four

months. Then he gave us

foglie rose

(pink slips of paper) permitting us to drive during the interval. He also gave us a manual of road regulations to study, along with a book of sample written tests. These tests had a reputation forbeing almost sadistically difficult, mostly because they exalted the principle of the trick question. An example:

When encountering this sign,

| 1. One must decrease speed | TRUE | FALSE |

| 2. One must drive with prudence | TRUE | FALSE |

| 3. It is forbidden to pass | TRUE | FALSE |

One and two are true. Three, however, is false. When driving through a

cunetta

(dip in the road) it is, in fact, legal to pass, even though, quite obviously, one would be unwise to do so.

cunetta

(dip in the road) it is, in fact, legal to pass, even though, quite obviously, one would be unwise to do so.

Fortunately, we were not going to have to take the written quiz; a fact that did not in any way mitigate our anxiety. For two months we studied. Both of us, by nature, are studiers, and in fact, it proved to be well worth doing. After years of driving in Italy, we finally learned the meaning of certain enigmatic road signs:

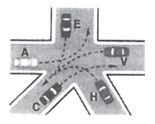

Obviously it is important to know what signs mean, just as it is important to know the basics of giving first aid after an accident. On the other hand, the many pages of the manual devoted to

precedenza

(right of way) demonstrated amply why this part of the exam was known as “theory.” After all, a drawing such as the one below, illustrating an intersection of five streets at which there is neither a stop sign, a stop light, nor a yield sign, and requiring the testee to adduce the sequence in which the various cars should give way to one another, has little to do with reality. Intersections of this sort, quite simply, do not exist, and even if they did, in Italy “right of way” belongs to the speediest, the most aggressive.

precedenza

(right of way) demonstrated amply why this part of the exam was known as “theory.” After all, a drawing such as the one below, illustrating an intersection of five streets at which there is neither a stop sign, a stop light, nor a yield sign, and requiring the testee to adduce the sequence in which the various cars should give way to one another, has little to do with reality. Intersections of this sort, quite simply, do not exist, and even if they did, in Italy “right of way” belongs to the speediest, the most aggressive.

Other books

The Best of Connie Willis by Connie Willis

Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child by Francisco Jiménez

Tempting the Cowboy by Elizabeth Otto

Parlor Games by Maryka Biaggio

Patch Up by Witter, Stephanie

Black Star Nairobi by Mukoma wa Ngugi

The Giving Season by Rebecca Brock

Alice: Slave at the Marketplace by Aphrodite Hunt

Show Business by Shashi Tharoor

See If I Care by Judi Curtin