In Tasmania (19 page)

Authors: Nicholas Shakespeare

TWO MONTHS AFTER ESCAPING MEREDITH'S CORDON, THE OYSTER

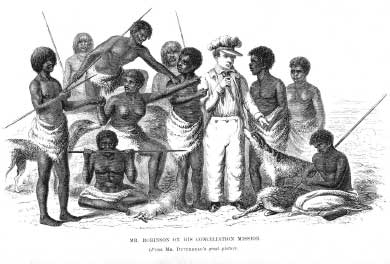

bay chief was found camped in thick bush a few miles north-west of Lake Echo where he and 13 others had joined up with the Big River tribe. The man who discovered him was George Robinson, a tubby 43-year-old sycophant with a head of wavy auburn hair, most of it a wig. When Tongerlongetter spied this puzzling Englishman, he advanced towards him crying his war whoop and shaking his spear. But the noise died away as Robinson stood his ground.

Robinson was a Wesleyan and former bricklayer appointed by Governor Arthur to negotiate peace with the Aborigines. A remarkable though vain and flawed man, he shared a passion for the fate of the Aborigines that was equalled only by his ambition to rise in his own society. He sometimes used one concern to promote the other. Calder knew him well: âHe was more patronising than courteous and somewhat offensively polite rather than civil.' His dispatches to Arthur, wrote Calder, were interminable and âin magniloquence of style throw into the shade altogether the official bulletins of such men as Napoleon, Wellington and others'.

An Aboriginal woman in Swansea told me 170 years later: âRobinson, as far as I'm concerned, was a weak, egotistical do-gooder who did real bad!'

Mark Twain, however, was impressed. âIt may be that his counterpart appears in history somewhere, but I do not know where to look for it ⦠Marsyas charming the wild beasts with his music â that is fable; but the miracle wrought by Robinson is fact. It is history â and authentic; and surely there is nothing greater, nothing more reverence-compelling in the history of any country, ancient or modern.'

Robinson had his extraordinariness and his journal at least rivals Baudin's report as the richest source of knowledge concerning Aborigines.

As Robinson described it in his journal: âI then went up to the chiefs and shook hands with them. I then explained in the aborigines' dialects the purport of my visit amongst them. I invited them to sit down and gave them some refreshments and selected a few trinkets as presents which they received with much delight. They evinced considerable astonishment on hearing me address them in their own tongue and from henceforward placed themselves entirely under my control.' In words that Tongerlongetter's descendants remember to this day, Robinson wrote: âI have promised them a conference with the Lieut. Govr and that the Governor will be sure to redress all their grievances.'

On January 7, 1832, Robinson led Tongerlongetter into Hobart. The two tribes had shrunk to a total of 26: 16 men, nine women and one child. Along with them followed more than 100 dogs. They walked down Elizabeth Street with their dogs, watched by citizens such as Kemp âwith the most lively curiosity and delight'. At Government House, Governor Arthur greeted their arrival with a military brass band and gave each Aborigine a loaf of bread. A large front door was then hauled onto the lawn so that they could demonstrate their âwonderful dexterity'. Among the observers was Jorgenson. âAt the distance of about 60 or 70 yards they sent their spears through the door, and all the spears nearly in the same place. âThen one Aborigine stuck a crayfish onto a spear, retreated 60 yards and hurled two out of three spears through the bright orange shell. The fact that they were in âthe greatest good humour' reflected their understanding that they were celebrating a treaty, not a defeat.

8

Ten days later Tongerlongetter boarded the

Tamar.

He had agreed to Arthur's complex negotiation to exchange Van Diemen's Land for Flinders Island. Robinson wrote: âThey are delighted with the idea of proceeding to Great Island [as Flinders was called], where they will enjoy peace and plenty, uninterrupted.'

I FLEW TO FLINDERS, A 35-MINUTE FLIGHT IN A SMALL PLANE FROM

Launceston with two other passengers. The sky was grey as a beard and Flinders rose into it, a bleak spine of rock springing sheer from the sea. Forty miles long and 23 wide, this was where Tongerlongetter allowed himself to be removed in exchange for his ancestral lands. The airstrip was surrounded by scorched meadows and at the empty terminal building there was a warning: âEuropean wasps are active in this area â please dispose of rubbish with care.'

Robinson had promised Tongerlongetter that if he came here his people would be able to keep their way of life. Instead, they were forced into Christianity and trousers, and told by the superintendent to scrub the mud and rust from their hair.

The Aborigines camped at an unsuitable lagoon near Whitemark while convicts built the settlement of Wybalenna for them, and in 1833 they moved there. The name Wybalenna meant âBlack Man's Houses'. For many, it was their last home.

Flinders is geographically to Tasmania what Tasmania is to the mainland. A young man in the pub at Lady Barron tried to explain it: âSometimes you think in Tasmania: “This is the best kept secret.” Then on Flinders you think: “

This

is the best kept secret of that secret.”' Its history lies close to the surface. A woman told me that her father, as he was putting down a cattle-race at Prime Seal Island, found a leg in leg-irons. He said: âI moved it further away.' For more than a century, that is how many settlers on Flinders tried to deal with what happened to the Aborigines at Wybalenna.

I found the bricks still scattered in the damp grass: the foundations of eight houses for the military, the sanatorium and dispensary, and, behind a mound, the L-shaped terrace of 20 cottages built for the Aborigines.

The only building standing today was a brick chapel built by George Robinson in a grove of casuarinas. It was here that Greg Lehman had got married in 1985. He told me that not long before my visit two Aboriginal women had tried to enter, but the door refused to open. They pressed their ears to it and what they heard made them walk away, very fast. âInside, they said, they heard a roaring, blowing wind.'

No-one escapes the wind on Flinders. Almost the first thing I noticed on the road from the airfield were the doubled-back trunks of the paperbarks, sculpted by the Roaring Forties to resemble trees from a children's book. The latitude splits the island in half. âYou are now passing the 40th parallel,' read a white signpost on another deserted road. Below it, someone had scribbled: âOh, what a feeling.' I lodged nearby with an old Scottish woman who complained how the wind transformed all her vegetables into propellers. âI've watched from my bedroom window a cabbage plant being blown round and round and then spin right off out of the ground.'

I arrived on Flinders shortly after the wind had fanned a forest fire across the island. The fire blazed for three weeks, driving flames from the hills in every direction and leaving the fields in their wake a dramatic rust colour. Clumps of ti-trees stood out like puffs of solidified smoke, and already in the forks of the burned branches the shoots were coming back in feathery green stems.

At Wybalenna, it had stopped raining and on the mound above the chapel the crickets were shrilling. But it was on a day like today, windy and damp, that Tongerlongetter caught his cold.

Â

He sat in his wet English clothes, no animal fat on his massive body â the superintendent discouraged that too â and shivering.

On the evening of June 19, 1837, he was joking with his wife when he collapsed in âexcruciating agony' and started vomiting. Earlier he had complained of a rheumatic pain on the left of his face, but now his chest was so inflamed that he howled when Alexander Austin, the medical attendant, touched his skin. Austin immediately bled him, taking 50 ounces from his arm, and administered an enema. âFor the first six hours he was perfectly sensible and his cries of “Minatti” piteous.'

Robinson had already that winter watched 14 Aborigines die from pneumonia. The prospect of losing the chief whom he had renamed King William was too much for him. âPoor creature!' he wrote in his journal. âI turned from the appalling scene. It was more than my mind could endure â¦' He left the room without saying goodbye. Later, he heard the lamentations and knew.

Not until the wailing died down did Robinson go and see the corpse. âOh, what a sight,' he wrote. The Aborigines stood in silence, tears streaming down their cheeks. He left the room, shaken. âThe death of King William has thrown a halo over the settlement.'

On a remarkably fine morning two days later Robinson led the mourners at the Christian funeral. Tongerlongetter's body lay in a gum plank coffin on two trestles in the schoolroom. At 11 a.m., the Aborigines in new dresses sang an improbable hymn: âFrom Egypt lately come/Where death and darkness reign/We seek a new a better home/Where we our rest shall gain.'

Then Robinson addressed them: âWhen I first met him he was in his native wilds, those parts where white men never trod. He was then at the head of a powerful tribe. Their very name spread terror and dismay throughout the peaceful settlements of the colony ⦠It was to subjugate this man's tribe and that of his colleague that the famous military operation was entered upon, namely the cordon of the island commonly called the Line.' But as the eulogy went on, Robinson faltered. He looked into the faces around him and thought of how Tongerlongetter's people had since been treated after relying âwith implicit confidence on my veracity'. He battled to console himself that at least they had discovered Jesus. âMy sable brethren,' he told them, âyou now not only have a knowledge of God, but you have a knowledge of the principles of Christianity.' But his heart was heavy. He had portrayed himself as a Pied Piper, promising to lead Tongerlongetter to safety and civilisation. In a letter he wrote to the surgeon, he could not contain his bitterness: âHe is no more and the white man may now safely revel in luxury on the lands of his primeval existence.'

Â

I could see the cemetery through the chapel window. One half contained the graves of Europeans; the other half was an empty field. The 100 or so Aboriginal graves were once indicated by wooden pegs painstakingly laid out on the mowed grass, but one night a farmer ploughed them up.

The crickets added to the sense that Wybalenna was a haunted place. On a clear day, Tongerlongetter's widow would climb up to Flagstaff Hill and peer with longing towards Tasmania's north-east coast, 60 miles away. I thought of another ghost story that Greg Lehman had told me. âIn the early 1980s, some Aboriginal kids went and sat on the hillside above the graveyard to watch the sun set. They sat up yarning, but when it got dark they were terrified to see a number of lights rising from the graves.'

On June 22, 1837, Tongerlongetter was buried somewhere beneath the undulating strip of grass. His widow followed soon after.

Jetty at Wybalenna

AT THE TIME OF KEMP'S ARRIVAL ON THE TAMAR IT IS THOUGHT

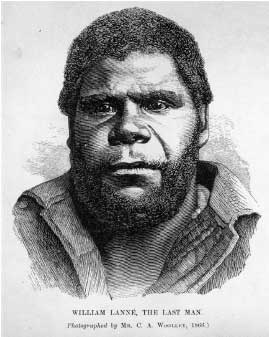

that there were nine tribes of Aborigines in Tasmania, with between 250 and 700 members each. It is impossible to know accurately their total population, but educated estimates range between 3,000 and 5,000. There were some 400 alive in December 1831, the month that Tongerlongetter submitted to Robinson. When Kemp died in October 1868, there were 103,000 Europeans on the island, but only one full-blooded male Aborigine.

In the museum at Wybalenna there was a photograph of William Lanne. He was dressed in a waistcoat and a canvas shirt with leg-of-mutton sleeves, and wore a colourful neckscarf. But the energy seemed punched out of him. He stared at the ground, unsmiling, his brow furrowed. The face of a man sick of being looked at. Sick of what he had seen.

He was brought to Wybalenna when he was seven, but ended his days in Hobart. At a regatta some years before his death, he was introduced to the Duke of Edinburgh as âthe king of Tasmanians'. He stood on a podium with Truganini and watched her present a prize for the crew of

Duck Hunt

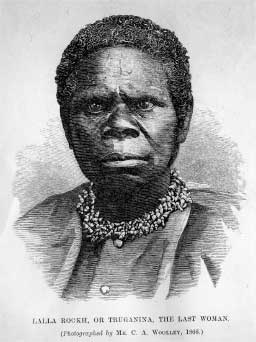

â and then, âdelighted with his share in the proceedings', called for three cheers. His spirit had been crushed several years before. In 1847, the Aborigines were removed once again â from Wybalenna to a settlement south of Hobart. Lanne's impotence shrieked out between the lines of his complaint that the women, including Truganini, were receiving inadequate rations: âI am the last man of my race and I must look after my people.'

He died on March 3, 1869. He had come off a whaling ship and taken a room at the Dog and Partridge Hotel in Barrack Street when he fell ill with choleraic diarrhoea. At 2 p.m., he got up, began to dress and collapsed. He was 34, known by the locals as a drunk who escaped his sorrows in pubs along the wharf, but remembered by his people as âa fine young man, plenty beard, plenty laugh, very good, that fellow'.

Lanne's death had about it the grisliness of a horror movie. His body was laid out in the morgue at the Colonial Hospital, but that night his head was cut off and the skull of a dead English schoolteacher called Ross inserted in its place. Soon after, it was rumoured that Dr William Crowther of the Royal College of Surgeons had left the hospital carrying a mysterious parcel under his arm. Lanne's skeleton then became the object of a tug of war between two warring scientific bodies, one of which sent his skull back to England while the other cut off his hands and feet. In a sickening note that I found among his papers, Calder wrote that Dr George Stokell of the Royal Society of Tasmania had a purse made out of Lanne's skin, and that Pedder, at one time Superintendent of Police, had called at Stokell's little surgery at the hospital and seen the skin pegged out on the floor. A magpie and a terrier dog were standing by, and there were buckets in the room âchock-a-block' with Lanne's âfat'.

Truganini's grief when she heard of his death was âsomething terrible'. She survived Lanne by seven years, coming to live with Mrs Dandridge at 115 Macquarie Street along from Kemp's first warehouse. She sat on the steps smoking a pipe or went walking around Battery Point, her dark face framed by a red turban, and a necklace of green and white Mariner shells in her pocket to give to Margaret's grandmother in return for beer. âShe was under four feet in height and of much the same measure in breadth,' wrote Sir Charles Du Cane, the Governor, who sometimes welcomed her at Government House, where someone described her as chuckling like a child over a slice of cake, a glass of wine. On May 3, 1876, she had a premonition. She gave her pet bird to Mrs Dandridge's son and in the evening screamed out, âMissus, Rowra catch me, Rowra catch me!' She did not speak again until shortly before her death five days later, when, remembering William Lanne's fate, she called, âDon't let them cut me, but bury me behind the mountains.'