In Tasmania (24 page)

Authors: Nicholas Shakespeare

I OPENED

Round the World Cruise Holiday

AS SOON AS I GOT BACK

to Dolphin Sands. I had only read a few pages when I felt my heart drumming.

Round the World Cruise Holiday

was co-written by my grandmother Gillian, who had embarked on the cruise on the

Southern Cross

without her husband. SPB explained his absence in a short preface: âOn this occasion owing to heart trouble I had to stay behind and while she wrote the story of her very exciting voyage I wrote notes on the historical background of the places she visited.'

Gillian was nervous travelling on her own: âFor so long now, 41 years to be precise, Petre has been my guide, philosopher and friend, in fact my all, and we have never been separated for more than a week â¦' Among the items she took with her to keep her company for the next three months was a photograph of her eldest grandson that she pegged to a board in her cabin beneath a brass dolphin.

It was amusing to read how much of my grandmother's time in Australia had been taken up looking for a suitable present to bring back for me. In Melbourne, she fingered a boomerang. But after feeling its hard edges, she decided that I might do untold damage to my sister. (The Aboriginal owner gave a demonstration, throwing it across the road. It dropped short on the return and a car deliberately âswerved to run over it and break it in half'.) In the Barossa Valley, she gripped an Aboriginal spear that was intended to pass through the body with a single thrust. âI was more sure than ever after handling these weapons that Nicholas should not have one.' When I read what present she did buy me, a memory came spinning back. A strange boarding house in Oxford. My grandfather impatient to get to the bus station. My grandmother plucking two packages from her bag: a curved piece of wood with odd-looking scribbles burned into it, and a peculiar animal, flat-nosed with claws, which the boys in my dormitory would take fantastic pleasure wedging between the roof beams.

The boomerang and the toy koala helped to staunch my peculiar form of homesickness, which could not be truly described as homesickness since I had no home. They were also, as I understood, nearly 40 years on, my first contact with Australia. And why, since a boy, I had felt an emotion comparable to the one which Andrei Sinyavsky describes in

A Voice from the Chorus

. âWhenever one sees Australia on the map one's heart leaps with pleasure: kangaroo, boomerang!'

MY GRANDFATHER WAS SENT TO STAY WITH HIS RECKLESS UNCLE

in Devon at the same age as I was when I went to the Dragon School in Oxford.

Hordern's two estates were on the fringe of Exmoor. Yarde, near Stoke Rivers, lay in a hollow with no view of the sea, a long low white house with a hornet's nest right outside SPB's window. The hall gave off the odour of old timber. âEver since I first smelt that strange unanalysable smell,' SPB wrote, âI have been under the spell of Devon.'

Hordern

Yarde was occupied by Hordern's maiden sisters, who, in their relations with SPB, pursued what he called âa consistent policy of “No!”' He wrote: âI wasn't allowed to play even solitaire on Sundays and no book was allowed to be opened except

The Quiver

or

The Sunday at Home

.' Conversation at meal times was never lively. âI remember that in the evening Fanny and Bertie used to rise from their seats exactly as the clock struck ten and without a word of “Goodnight!” would disappear to their respective bedrooms.'

Into this world stormed their brother in his dogcart, popular and spirited, who liked to dress well, even nattily, in white spats, with a gold toothpick flashing from his mouth and smelling of milk to disguise whatever he had had to drink.

Hordern rode SPB back the 17 miles to Boode House, near Braunton, whipping his horse on with a silver-handled crop â a drive not without hazard since at a certain point Hordern preferred to sleep and leave it to his horse to pick its own way along the high-banked Devon lanes. âSo great was my confidence in my uncle that I, who always accompanied him on these trips, which were usually in the dead of night, also went straight to sleep soothed by the rhythmical jog-trot of the horse.'

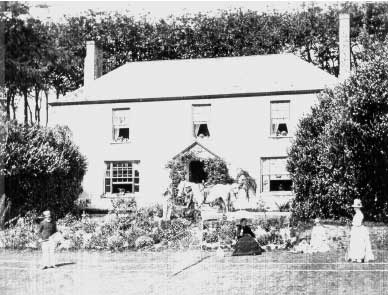

Their destination â Boode â was Hordern's headquarters and the birthplace of SPB's mother: a rambling whitewashed farm with a huge garden that stood at the top of a narrow coombe. The two lighthouses that SPB claimed he could see from his bedroom window cast the same spell over him as the entrance hall at Yarde. He spent, he wrote, âjoyous hours' looking out at night over the sandhills and the flashing lights of Lundy and Hartland Point to Westward Ho!, the place named after Charles Kingsley's novel, and where Rudyard Kipling had been at school, and which he wrote about in

Stalky & Co

. Hordern took both books with him to Tasmania.

At Boode, SPB met his first author: a fruit-grower who had written the popular Exmoor romance,

Lorna Doone

. Richard Blackmore, he wrote, was âa large-hearted, lovable sort of a man' with broad, sagging shoulders and a benign, rosy face, whose uncle had the curacy of Charles, ten miles away. He did not look like a novelist and he shunned society. âAn air of rusticity enveloped him,' remarked a contemporary. âNot the material rusticity of the farmyard, but that of the wind and the scents and the voices of the open spaces ⦠he seemed to exhale the very presence of the moorland and coombes he loved and interpreted so well.' Blackmore had tried school-teaching and market gardening before taking up historical fiction, and Hordern regarded him as his mentor.

Hordern's Wife

Blackmore often strode up the muddy lane to visit Boode. He sat SPB on his lap and in a memorably low voice told stories of

Lorna Doone

's hero, the young farmer John Ridd, and of Ridd's love for a well-born, black-haired girl he had encountered in a moorland pool, and of the band of wild desperadoes who had kidnapped her, whose lair was in an unget-at-able place in the hills among the rocks of Exmoor. When SPB came to describe his upbringing, this was the experience he singled out. âNothing can destroy the fact that I spent an idyllically happy childhood on these two farms. Nothing can destroy the fact that R.D. Blackmore with his strong Devon “burr” used to come over from Charles and dandle me on his knee.'

Blackmore was not the only influential figure at Boode. There was Hordern's wife Penelope. Hordern had courted her assiduously and talked of her as his own Lorna Doone. âShe was one of the Downings of Pickwell Manor, Georgeham,' SPB wrote. An elegant, large-nosed lady with a direct gaze, she was never heard to say a bad word about anyone, least of all her husband, but because of him she would end her days a long way from Georgeham, perpetually dressed in black, sitting bolt upright in a rented dining room, knitting cardigans and praying. Once upon a time, when Hordern had courted her, she had loved to dance, but religion had become her tipple. When her brother drowned in the

Stella

off the Channel Islands, it was felt that he deserved his fate âfor travelling on so holy a day'.

Less pious were Hordern's eight children. âMy cousins were a rackety crowd, and we were allowed more or less to run wild at Boode, of which I remember best the fragrant smells of the stables and the harness room, the peaches on the south wall, the gaily coloured if somewhat crude glass in the front door and greenhouse, the thick laurel bushes in the drive â¦' SPB was an only child of remote parents. It was easy to understand why Boode became his second and happier home, and Hordern's children his earliest friends. They formed, he wrote, a self-contained and completely content unit. Best of all his cousins, SPB liked Hordern's youngest son Brodie, who everyone agreed was a dead ringer for him. He and Brodie used to play hide and seek in the laurel bushes. âLooking back, I find these were days of pure enchantment.'

The Hordern Family

On hot summer days Hordern rode them in his large hay-wagon down to Croyde Beach where they bathed and raced each other on surfboards. SPB's description evokes the feeling that I had when walking with Max along Dolphin Sands: âMy cousins and I used to walk along the banks of the Pill, climb on round the old wooden hulks, bathe naked from the sand dunes in the Estuary, set fire to the marram grass, which screams like a child in pain as it burns, play hide and seek in the vast solitude of the Himalayan sand dunes, watch fishermen pull in the salmon in their nets ⦠and sometimes halt to remove the thorns from our bare feet. I seem to have spent the greater part of my Devon childhood days barefoot.'

If SPB's cousins were his best friends, then his spirited uncle took the place of a father. In autumn, under Hordern's tutelage, SPB followed the stag-hounds on foot through North Molton; and on Fridays drove with him into Barnstaple market where Hordern bought and sold cattle. Hordern's herds and flocks were among the finest in the country, winning prizes at agricultural shows from Launceston to Norwich. Sounding a premonitory note, SPB remarked that after market was over his uncle âinvariably bought me some outrageously expensive present. His generosity was not confined to me. He went bankrupt because he could not find it in his heart to refuse anybody anything. He was the kindest man I have ever known.'

Hordern passed on to SPB his taste for books, his love of Devon, and his talent for extravagant living. He was perpetually hosting large parties at Boode at which champagne freely flowed. âHe enchanted me by his behaviour,' SPB wrote. âI can't remember whether he drank champagne for luncheon regularly, but I do remember how delighted I used to be when he took up empty champagne bottle after empty champagne bottle and hurled them one after another through the large dining room window on the lawn outside. I remember this lawn contained more broken glass than grass because we used to try to play tennis on it.'

One day in 1900 the champagne ran out. Cleaned out by his generosity, Hordern put the two estates up for auction. They had been in the family's possession 700 years, since the reign of King John. Four months later, having earned his sisters' âlasting enmity' for going through their money, he booked his passage for Tasmania.