In the Valley of the Kings (18 page)

Read In the Valley of the Kings Online

Authors: Daniel Meyerson

Tags: #History, #General, #Ancient, #Egypt

Watching the spectacle even from this distance in time, one wants to cry out: No! Stop it! Control yourself, Carter! But the truth of the matter is that Carter could not control himself. For though he was remarkable, he was also a little—more than a little—crazy. You couldn’t be Howard Carter and not be. The same driven quality that enabled him to find Tut’s tomb also brought about his downfall.

Weigall privately circulated a caricature he’d drawn of Carter looking very much like Charlie Chaplin. In the sketch a ragged Carter hit the road, following a sign advertising cheap lodgings. Weigall especially had little sympathy for the ex-chief inspector: Carter had brought the Saqqara trouble upon himself, Weigall wrote to his wife, the man was filled with childish pride, vanity, and stubbornness.

Say Weigall was right, Carter’s flawed character had led him to resign—his pride, vanity, and anger. Or say Carter was right, that a strong sense of principle and ethical disgust made him throw in the towel. Or—probably the case—say both were right: In the end it came to the same thing. The strong flow of Carter’s feelings, the intensity that made him abandon his post at the service, was also what led him to make the greatest discovery in the history of Egyptology … perhaps a bad moral with which to conclude, but an interesting reflection on our human nature.

Right or wrong, Carter was suffering, alone and without a penny, after his resignation. But the insult he had received only fueled his determination. He might be down in Cairo—but he was not down and out.

One Month Later

Cairo was a city of refuge for outcasts. It was blind to faults, forgiving of sins, delighted by scandal. When Lady Atherton, for example,

was exposed as an adulteress by her French maid, where did she go? She left the terribly straitlaced London and came to Cairo, of course, where the new inspector of antiquities—Arthur Weigall—squired her around. Or, to take another example, when Prince Oblonsky lost everything at the Baden-Baden casino, where was he next seen? In Cairo, naturally, where he was all but applauded for his prodigality.

Even that supposedly virtuous dame the Statue of Liberty planned on taking up residence here. (Her original name was

An Allegory of Egypt Holding Out the Light of Learning to Asia.

She was intended as a gift from the people of France to Egypt.) But King Isma’il of Egypt was going bankrupt and didn’t have the dough to bring her over from France. Otherwise she might have been the Statue of License, not Liberty, and her inscription would have proclaimed: “Give me your spendthrifts! Your lustful! Your social outcasts yearning to be free!”

Only one outcast was beyond the pale—the unrepentant Carter. After resigning as chief inspector, he was cold-shouldered by the elite and blacklisted as an excavator. It was not official, of course, but for the next three years, all doors were shut. Nothing could open them—neither Maspero’s affection for him, nor the efforts of Percy Newberry his old Beni Hasan colleague, nor his brilliant record as inspector. He had ordered Egyptians to beat Europeans. (“That is the really bad part of the business,” Maspero wrote to Carter in an off-the-record letter. “Native policemen ought to let themselves be struck without striking back.”) No, Carter had proved himself not to be a gentleman. He was all washed up.

The only reasonable course of action, he knew, would have been to beg, borrow, or steal the return fare to England. But instead, Carter used whatever money he had to head south, to the Valley of the Kings. When he got off the train at Luxor in 1905, he had no place to live, no money, and no idea whether he would be able to support himself.

The American Egyptologist James Breasted reported firsthand (and Breasted’s son has confirmed) that Carter went to live in the hut of an Egyptian tomb guard whom he had fired. He ate at the man’s table and even borrowed money from him. What Carter’s fellow Europeans thought about this arrangement may be easily guessed. But Carter did not care. He was determined to find a way of remaining in the Valley and quickly settled into a routine, spending his nights in the hut at Gurneh (the desert’s edge) and emerging each morning to paint the ruins.

The ex-chief inspector at his easel—what an astonishing sight it must have been for the beggars, urchins, and thieves he had driven away. Now they were thrown not into the Karnak temple jail, but into Carter’s paintings, where they were used to create local color—a child playing at the entrance of a tomb, a beggar stretching out his hand under a crumbling arch. It was not great art, but it was salable, that was the main thing: It appealed to all sorts of people passing through Luxor and helped Carter keep body and soul together.

He developed other sidelines as well. He became a familiar figure at the ruins, taking around visitors who wanted a deeper understanding of their history. He was to be seen in the bazaars, offering his expertise to those who were interested in purchasing antiquities but were afraid of ending up with one of Oxan Aslanian’s “masterpieces” (the great Berlin forger was working in Egypt during this time).

Now and then, the thieves themselves helped Carter to earn a commission. We find him approaching the American millionaire Theodore Davis on their behalf (at that time Davis was digging, or rather bankrolling the archaeologist Edward Ayrton to dig, in the Valley, unmethodically, striking out in all directions for whatever they might find). Carter offered Davis a hoard of small precious objects, jewelry and scarabs, all stolen from his dig. For a fair price, they would be returned—no questions asked, no arrests made. It

was a mark of the thieves’ respect for Carter that they had made him their emissary—and a thief’s respect is worth having, especially in the antiquities game.

With such makeshift stratagems as these, Carter managed to survive while, unknown to him, the man who would be his future partner arrived in Cairo. And in style—the Earl and Countess of Carnarvon took a suite at Shepherd’s, where they prepared to remain for the 1905 season—or so the

Egyptian Gazette

reported.

It was not long, though, before Carnarvon tired of the social round and thought it might be just the thing to try his hand at some excavating. He took up the idea lightly. And though as time went on he pursued it with increasing seriousness, it never became the desperate obsession for him that it was for Carter. He never went slithering over mounds of debris in unstable tomb corridors or spent his nights brooding over maps of the Valley of the Kings.

But as his enthusiasm grew, so did his commitment. Especially after World War I, when inflation ate away at his income and the sums spent on his work with Carter mounted higher and higher, he was tested. And though his test was only a financial one, still Carnarvon cared greatly about money, not to mention the fact that he had heavy expenses maintaining Highclere Castle, his ancestral estate.

In 1905, however, Carnarvon began with a simple proposition—that it would be very pleasant to sit in the shade, watching as objects of rare beauty were dug up from the earth. Using influence, he obtained permission to excavate in the hills near Hatshepsut’s terraced temple. His plan was to go it alone with only a team of workers. But though he had no interest in engaging an archaeologist, or “learned man,” as he called them, still and all as he traveled south to begin his dig, the paths of the earl and the outcast Carter had begun to converge.

The Fourth Earl of Carnarvon, 1831-1890.

Influential statesman and classical scholar.

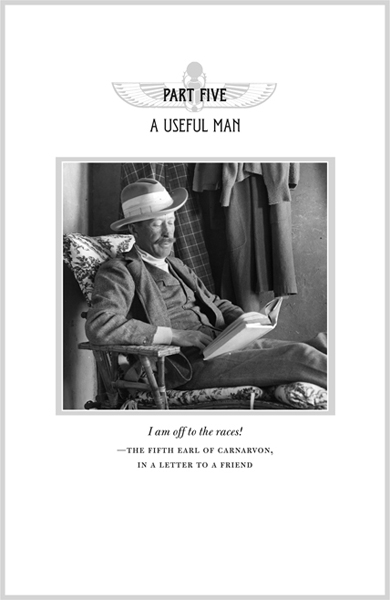

The Fifth Earl of Carnarvon, 1866-1923.

Patron of Howard Carter. Financed five years of digging

in Thebes, followed by seven years of digging for King Tut’s tomb.

The Sixth Earl of Carnarvon, 1898-1987

Lord Porchester until he succeeded to the title in 1923.

International playboy who fell in love.

PREVIOUS PAGE: Lord Carnarvon.

© GRIFFITH INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

AH, THE EARLS … IF THE SIXTH EARL OF CARNARVON HAD

killed his father, the fifth earl, as he’d planned to, it’s hard to say what would have become of Howard Carter.

The Fifth Earl of Carnarvon was one of many rich men interested in digging in Egypt. Carter had even worked for some of them during his early years—when he was still learning and developing—before he came into his own. But they were reasonable men engaged in reasonable endeavors. That is, they expected a reasonable return, in a reasonable amount of time, for a reasonable investment of cash.

The search for King Tut’s tomb was not such an endeavor. It was begun amid warnings from every side that the Valley of the Kings was now exhausted: Even Gaston Maspero (who brought Carter and Carnarvon together) warned the earl that every royal tomb to be found there had been discovered.

There were good reasons for this pessimism, a pessimism that seemed to be confirmed by the results of the Carnarvon-Carter effort. To universal laughter, the spectacle of the futile excavation dragged on year after year for seven long years. The mounds of excavated rubble, meticulously sifted, piled higher and higher. Foot by foot, the area Carter had marked out was exposed to the bedrock.

The costs accumulated, the earl spent a fortune, and nothing

was found. But still Carnarvon toasted Carter each season with the best champagne as he good-naturedly shrugged off the past failures. His slouch hat worn at a rakish angle, the sun glinting on his gold cigarette holder, Carnarvon would invariably irritate the gloomy Carter with his unbounded, amateurish enthusiasm. This would be their year, the earl was always sure; there was no telling what, in the coming season, they would uncover.

Who else would have been so foolish? The other men backing expeditions and buying antiquities in Egypt, the Pierpont Morgans and Theodore Davises, were too hardheaded to invest their money so unwisely.