India: A History. Revised and Updated (104 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

When billed as the ‘Islamic bomb’, Pakistan’s nuclear ambitions nevertheless lent credibility to Bhutto’s international ambitions. With India’s non-aligned status disqualified by Mrs Gandhi’s treaty with the Soviet bloc, Pakistan took its place. Rejecting the British Commonwealth and SEATO, Bhutto fraternised with Libya’s Qadaffi and North Korea’s Kim Il-sung in an attempt to breathe new life into a movement whose membership had degenerated from post-colonial peaceniks into mad-cap mavericks. He fared better with the Islamic world. In 1974 Lahore hosted the second summit of the Organisation of Islamic Countries. With the exception of the shah of Iran, everyone from Sadat of Egypt and King Faisal of Saudi Arabia to Arafat, Assad and Qadaffi attended. A magnanimous Bhutto even welcomed Mujib of Bangladesh. The spectacle dispelled any sense of Pakistani isolation and, coming hard on the heels of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, reassured more than one wounded nation.

Unfortunately old wounds were being replaced by new ones. PPP support in the 1970 elections had come almost exclusively from Panjabis and Sindhis. Elsewhere other loyalties prevailed. In the NWFP a Pathan party led by the imposing Wali Khan, son of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the pro-Congress ‘Frontier Gandhi’, sought greater provincial autonomy as per Mujib’s six points plus closer relations with its Pathan brethren in Afghanistan. It would be Wali Khan’s boast towards the end of his long career that he had been incarcerated

by every regime in Pakistan’s history. That of the PPP was no exception. Plagued by assassination attempts and assaults on his party workers, often the work of the thugs in Bhutto’s paramilitary Federal Security Force (FSF), Wali Khan retaliated by characterising the PPP as fascist and referring to its leader as ‘Adolph Bhutto (with no disrespect to Mr Hitler)’.

4

Others noted Bhutto’s borrowings from Mao. ‘Chairman Bhutto’ (of the PPP), as he was happy to be called, took to wearing high-collared tailoring, occasionally donning a forage cap and commissioning a handy little book of his pithier utterances.

The NWFP churned with rage throughout the 1970s. So did Sindh, where Karachi and Hyderabad (not be confused with the city of the same name in India) witnessed pitched battles between native Sindhi-speakers and Urdu-speaking

mohajirs

over jobs, development projects and the admission of more

mohajir

refugees from Bangladesh. In Baluchistan the situation was worse. There, within two years of the Bangladesh fiasco, the Pakistani army was again called into action in defence of the nation’s integrity. Although the so-called revolt was this time suppressed, it was at a heavy cost both to the province, which remained under military occupation, and to Bhutto, who acquired the new sobriquet of’Butcher of Baluchistan’. Even in Panjab there was widespread unrest as the lately nationalised industries floundered, the economy stalled and more and more of Bhutto’s PPP lieutenants grew disillusioned. By way of consolation the ‘chairman’ scanned the massed ranks of Pakistan’s top brass for a devoted, workaholic and politically unambitious general to take over as chief of staff. Just as Ayub had lit on Bhutto as his acolyte, Bhutto lit on the little-known Zia-ul-Haq. The appointment was confirmed in 1976.

In January 1977, more with the idea of boosting the PPP’s flagging popularity than testing it, Bhutto called for national elections, the first since 1970. This had the unexpected effect of energising and uniting the otherwise motley array of opposition parties. Despite the continued detention of Wali Khan, its potential leader, a Pakistan National Alliance of ethnic, Islamic and conservative groupings duly took the field. With only a matter of weeks in which to organise itself, it was defeated. The PPP captured more than two-thirds of the seats. On the other hand the Alliance, with 30 per cent of the votes cast, took heart, and thus the real campaign came not before the March ballot but after it.

Claiming that the PPP had managed the elections to its own advantage, engineered the elimination or disqualification of other contenders and rigged many of the results, the Alliance called for a nationwide strike. Bhutto offered talks and an inquiry, concessions that seemed to hint that electoral

irregularities had indeed taken place. The near-total paralysis induced by the strikes and protests seemed to endorse the opposition’s demand for a re-run. Amid mounting violence and heavy casualties, especially in Karachi and Lahore, even Bhutto’s dreaded FSF proved unable to quell the ferment. That left only the army as the guarantor of public order. When Bhutto’s last-minute concession over a second ballot failed to convince the opposition that it would be any fairer than the first, the die was cast. In time-honoured tradition, a concerned group of junior army officers is said to have prevailed on a reluctant General Zia-ul-Haq to invoke martial law, suspend the constitution and detain all political leaders pending a quick resolution of the crisis.

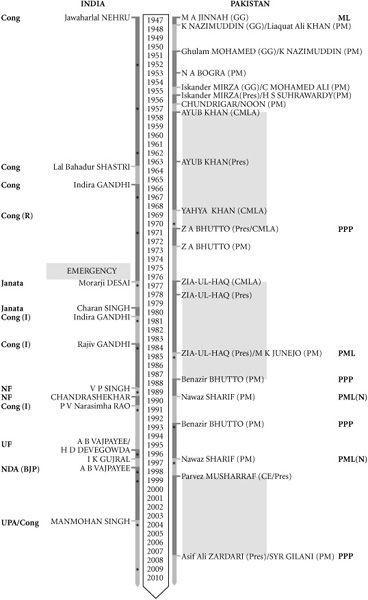

So began the longest period of one-man military rule (1977-88) in Pakistan’s history. The army had again bailed out the politicians – just as the politicans had bailed out the army in 1971, just as the army had bailed out the politicians in 1958. A pattern was emerging. It would be easy, though, to misinterpret it as indicating some irreconcilable polarity. The army could no more do without the politicians than the politicians could do without the army. Each depended on the other. Bhutto, like Jinnah and Liaqat, had carefully cultivated the military. Zia, like Ayub and Yahya, would never relinquish the hope of engaging civilian support. ‘To survive and succeed, an elected prime minister in the Pakistani context has almost to play the role of a leader of the opposition upholding the cause of the political process against the pre-existing state structure,’ notes Ayesha Jalal.

5

But to this ‘pre-existing state structure’ consisting of the largely Panjabi military-bureaucratic establishment, the politicians themselves subscribed and often belonged. Confrontation masked a subtle complicity. Coups tended to be gentlemanly affairs and not notably vindictive. Imprisonment often meant nothing worse than house arrest; the disgraced could expect a graceful retirement. Discounting unexplained and probably extraneous shootings like that of Liaqat Ali Khan, governmental heads rarely rolled.

But, in this as in much else, Bhutto would be the exception. Detained in July 1977, he was released in August but rearrested in September. Zia and his military supporters were either undecided on his future or unready for a trial of strength. Having promised elections ‘within ninety days’, they felt obliged either to let him contest them or to use his arraignment for electoral malpractice as a pretext for postponing them. His triumphal reception during his August release looks to have decided the matter. The elections were postponed and Bhutto cast back into gaol. It remained only to make a case against him, and in this members of his own FSF, who were themselves being interrogated and tried under martial law, proved suspiciously obliging.

Charged, somewhat randomly, with ordering the murder of an opponent, Bhutto put up a spirited defence and challenged not only the dubious nature of the evidence but the competence of the court and the legality of the regime it served. It changed nothing. His conviction in March 1978 was a foregone conclusion, as was the death sentence.

A lengthy appeal process ensued. Pleas for clemency and offers of asylum came from all over the world, including from the US, which Bhutto had accused of supporting Zia. But, true to his conceit about being the embodiment of the nation, he refused to tone down his defiance or forswear his destiny. Only death could be guaranteed to silence his peculiar brand of self-centred populism (and not even that if allowance be made for its dynastic aftermath). Zia, busy with an agenda of his own by the time the final appeal was rejected in April 1979, had little choice. On the morning of 4 April, after fond farewells with his wife and his twenty-five-year-old daughter Benazir, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was led to the gallows and hanged as a common criminal.

In a parting shot from his death cell in late 1978, Bhutto had linked Zia’s recent self-appointment as president of Pakistan with the assassination of the Afghan royal family in a communist coup earlier in the year. Zia’s action and its ‘downright burial’ of the 1973 constitution had turned Pakistan into what Bhutto called an Orwellian ‘Animal Farm’. On the other hand, the communist bloodbath in Kabul seemed to Bhutto a ‘tonic’.

6

The Great Game, that long-standing Anglo-Russian tussle for control of Afghanistan and beyond, was ‘over’. The Afghans had finally dispensed with their Western-backed monarchy and the imperialists had been sent packing. By implication there was hope for Pakistan yet.

But if Bhutto was looking to the day when Zia too would be overthrown by Marxist revolutionaries, he was whistling in the wind. The Kabul coup did lead, a year later, to Soviet troops being invited into Afghanistan as auxiliaries, then staying on as occupiers. But far from this occupation destabilising Zia’s neighbouring regime, it would prove its salvation. Overnight Pakistan was restored to front-line status in Washington’s frantic ring-fencing of the new communist breakout. Arms shipments to Pakistan were resumed, its nuclear transgressions were overlooked, so were its postponed elections, and the Great Game entered a new and more lethal phase. With the active involvement of a markedly more Islamic Islamabad, Washington would turn to the bearded exponents of an uncompromising Islamism for its proxy

jihad

against Afghanistan’s godless communists. The ‘tonic’ had turned out toxic. Bhutto had got it wrong again.

1984 AND ALL THAT

Ironically the one person who had unwittingly anticipated these developments was Indira Gandhi. For though the dangers of inflaming sectarian sentiments were nowhere better appreciated than in India itself, it was her government’s confrontation with India’s Sikhs, an emphatically non-Muslim community, that first introduced South Asia to the horrors of supranational terrorism. From 1977, by antagonising communal sentiment among the Sikhs and involving the army in its suppression, Mrs Gandhi set in motion a pendulum of violence and retaliation. As a sanctuary and source of arms, Pakistan became implicated in the Sikh conflict, and when in 1989 the pendulum’s deadly swing was extended to a still-contested Kashmir, Pakistan would prove an eager source of guerrilla support and training. Sectarian tensions throughout India and Pakistan would be excited and their bilateral relations further distorted. By the 1990s the baleful throb of bomb-for-bomb, bodies-for-bodies, would be echoed still further afield as the litany of state violence and terrorist outrage extended along the Afghan frontier in a jihadist arc from Kashmir to Baluchistan.

As early as 1984 sectarian butchery returned to the heart of the Indian capital, Mrs Gandhi herself being the first victim. The retaliatory carnage awakened memories of Partition; and the state’s complicity in it revived the explosive issue of India’s commitment to secularism. Then, in the following year, the deadliest ever terrorist attack on a civil airliner prolonged the cycle of violence. The downing by Canada-based Sikhs of Air India’s flight 182 over the eastern Atlantic killed all 329 on board, most of them South Asians of Canadian nationality – and it could have been worse. Had another suitcase-bomb not prematurely exploded at Tokyo airport, a second Air India jumbo would have been simultaneously blown to smithereens over the western Pacific. Concerted terrorist attacks, later regarded as the hallmark of the most ‘sophisticated’ Islamist cells, were being perpetrated by non-Muslim South Asians long before 9/11. In sum, Mrs Gandhi’s provocative interventions in Panjab in the 1980s anticipated, as to both their manner and their consequences, those of the US and its Pakistani surrogate a decade later in Afghanistan. And though of far greater consequence than her shortlived Emergency, in that failed experiment in extra-constitutional rule lay their genesis.

Back in 1975, when Bhutto still ruled supreme in Pakistan and Mujib headed a one-party state in Bangladesh, Mrs Gandhi had made her own lurch towards authoritarian rule. By declaring a state of ‘general emergency’ on 26 June that year she stunned the nation and sent shockwaves round the

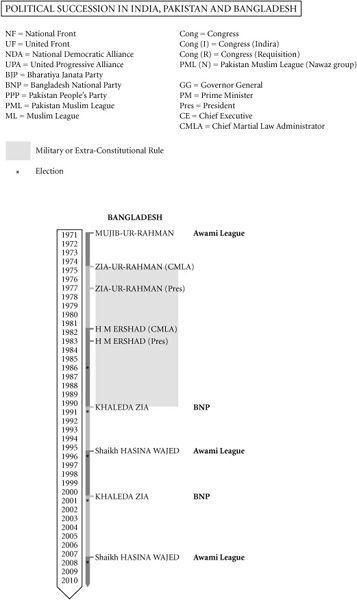

globe. As the beacons of personal freedom and liberal opinion went out all over the world’s largest democracy – quite literally so in the case of New Delhi’s newspapers where publication was halted by turning off the power supply – the murky extinction of Mujib-ur-Rahman amid the chaos in Dhaka passed almost unnoticed.