India: A History. Revised and Updated (50 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

The success of this price-fixing policy resulted in its extension to just about every other commodity known to the Delhi bazaars. Textiles, groceries, slaves, whores, cattle, in fact everything ‘from caps to shoes and from combs to needles’ had its fixed price and its market regulators. It was not just one of the first recorded examples of planned economic management but also one of the most ambitious. And therein partly lay its undoing. ‘A camel could be had for a

dang

[a farthing],’ says Barani, ‘but wherefrom the

dang

?’ Purchasing power seemed to decline just as fast as prices; and urban sufficiency brought only chronic rural depression. There was no incentive to increase yields. Nor was there any chance of so ambitious a system surviving the heavy-handed authority which alone had made its imposition possible.

When Ala-ud-din succumbed to sickness and then death, both markets and prices simply reverted to the usual free-for-all. Most of his reforms, like most of his conquests, were temporary expedients and anything but proof against the internecine succession crises which now again overtook the sultanate. In the space of four years two of his sons, plus a Hindu convert, occupied the throne and quickly paid the price – a price which, though not fixed, was invariably lethal. So did ‘Thousand-dinar Kafur’, who briefly acted as king-maker; half a dozen other pretenders were either blinded or murdered. Mubarak, the son of Ala-ud-din who occupied the throne for longest, turned out to be what Ferishta calls ‘a monster in the shape of a man’. Most of his indecencies were too gross to mention although not, strangely, his practice of ‘leading a gang of abominable prostitutes, stark naked, along the terraces of the royal palaces, and obliging them to make water upon the nobles as they entered the court’.

30

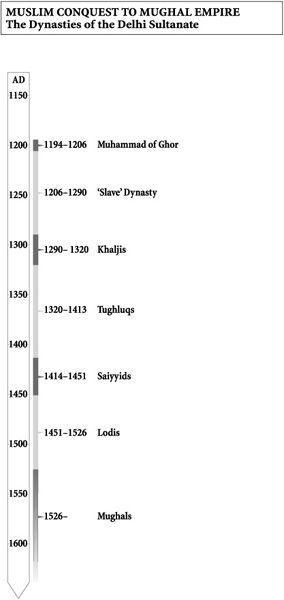

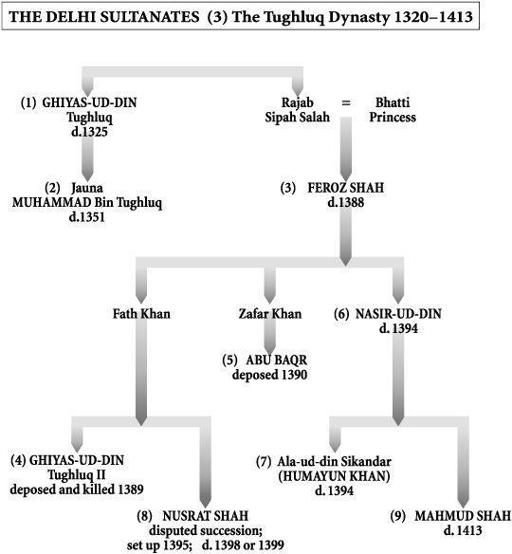

The Khaljis thus ended much as had the Slave kings. In 1320 Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq, the son of one of Balban’s slaves, emerged as the founder of a new dynasty. Briefly the Tughluqs would revive, and then fatally destroy, the fortunes of the sultanate, thereby surrendering Delhi’s presumed hegemony to a host of powerful new rivals. Far from uniting India, early Islam’s historic role would be to develop and entrench the subcontinent’s so-called ‘regional’ identities.

12

Other Indias

1320–1525

THE TUGHLUQS

E

AST OF THE

Q

UTB MINAR

, where the suburban sprawl of south Delhi picks its way into scrub, lie six square kilometres of monumental desolation. This wilderness of cyclopean ramparts and dungeons is Tughluqabad (Tughlakabad), the most far-flung of the dozen-odd citadels which, originally some sultan’s new Delhi, then his successors’ old Delhi, are now decidedly dead Delhis; the howling jackals by night, and by day the mewing kites, could be ghouls at large.

Built by Sultan Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq (Tughlak) in the early 1320s, Tughluqabad’s parapeted walls and bastions march uncompromisingly along a low ridge which overlooks a wasteland of goat-grazed acacia and wind-borne litter. Jets scream low on a flightpath into the airport; in the distance isolated outcrops of many-storeyed housing rise from the ground-haze like the islands of an archipelago. Today’s Delhi is still heading south, colonising the scrub with random developments and upgrading the goat tracks to feeder roads. The modern metropolis may yet reclaim Tughluqabad just as it already has the mosque of Qutb-ud-din Aybak, Iltumish’s Lalkot and the Siri fort of the Khaljis.

Below the walls of his Tughluqabad, Sultan Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq lies buried in a tomb of quite spectacular foreboding. Battlemented like the citadel, its steeply inward-sloping walls reminded James Fergusson, the nineteenth-century dilettante who first subjected India’s architecture to systematic study, of an Egyptian pyramid; he much admired the structure’s solidity, and memorably dubbed it ‘an unrivalled model of a warrior’s tomb’. But unlike the great grey citadel whose gigantic rough-cut stones fit so pleasingly in place, the squatly domed tomb is built with dressed precision from a rusty sandstone banded with off-white marble, both of

them streaked and blackened by countless monsoons. The whole composition sits in a dusty bowl, sometimes a bog, which was once an artificial lake. It is reached across a causeway of many arches where a portcullis would not go amiss. ‘Tughluq’s Tomb’ looks more like a place of detention than of repose.

Shaikh Nizam-ud-din Auliya, the Sufi saint and mystic after whom another bit of Delhi is named, must have rejoiced at the ghost of the first Tughluq sultan being committed to such secure confinement. Taking exception to what he saw as Ghiyas-ud-din’s laxity in matters of religious observance, he had famously laid upon Tughluqabad the curse which still holds good:

Ya base Gujar, ya rahe ujar

(‘Let it either belong to the Gujar [i.e. the herdsman], or let it remain in desolation’). He it was, too, who when warned to seek safety as the sultan drew near to the city at the end of a long campaign, still more famously gave the cryptic response ‘Delhi is yet far off.’ This proved to be an accurate forecast: the sultan never did reach Delhi. To Shaikh Nizam-ud-din’s followers his premonition was proof of his exceptional powers. But such was the animosity between saint and sultan that more suspicious minds saw the prophecy as evidence of complicity. It all depended on whether the sultan’s arrival was forestalled by accident or by design; and on this historians are still bitterly divided.

In 1320, emerging victorious from the five-year power struggle that followed Ala-ud-din Khalji’s death, Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq had skilfully combined the conciliation of rivals with the usual generosity towards supporters and kin. Prominent amongst the latter was his eldest son and designated heir, the future Muhammad bin Tughluq, who was despatched to the Deccan to deal with the ever-rebellious Kakatiya king, Pratapa-rudra of Warangal. Successful at his second attempt in taking Warangal, Muhammad had been recalled to Delhi in 1323 to act as viceroy while Ghiyas-ud-din himself ventured east. Affairs in Bengal had unexpectedly offered an opportunity for reasserting the sultanate’s authority there, while recalcitrant Hindus in the Tirhut district of northern Bihar also required attention. Both these situations were addressed with remarkably little bloodshed during the course of 1324–5. It was only when nearing Delhi at the end of this highly successful campaign that Sultan Ghiyas-ud-din ran into trouble.

To prepare for his ceremonial entry into his new citadel of Tughluqabad, he had ordered his son Muhammad to construct a timbered pavilion by way of temporary accommodation at a place called Afghanpur, which was evidently nearby on the banks of the Jamuna. This was done, and there father and son were duly reunited. Barani says simply that they dined together and that when Muhammad and other notables had retired to wash their hands at the end of the meal ‘a thunderbolt from the sky descended upon the earth, and the roof under which the sultan was seated fell down, crushing him and five or six other persons so that they died.’

1

It seems to have been July, a season of storms, and the pavilion was no doubt a conspicuous lightning conductor. But Barani is not usually so economical on affairs of magnitude. Perhaps, not having witnessed the disaster, he simply gave the official version; or perhaps the memory of those who stood by that version was not something he chose to ignore.

A very different account, though, was given by other writers, including Ibn Batuta, a distinguished Muslim scholar from Morocco whose twenty-eight years of adventure in three continents would make him not just ‘the traveller of the age’ but of most subsequent ages. Ibn Batuta began his long sojourn in India eight years after the Afghanpur tragedy, but his

Travels

would not be written until he was back in the safety of his native Fez, where neither fear nor favour can possibly have influenced him. Moreover, his version of the affair came from one who was actually present, in fact from another distinguished Delhi Sufi. Like Nizam-ud-din Auliya, this man had no love for the Tughluqs and may therefore have been happy to discredit them. On the other hand he offered a much more plausible account, insisting that the Afghanpur pavilion was meant to fall down, that Muhammad ordered up the ground-stamping elephants to make sure that it did fall down, that its collapse was carefully timed for the hour of prayer when the rest of the company would have moved outside, and that by design the shovels and pickaxes required to sift the rubble in the search for survivors did not arrive until too late. Additionally he thought it was no coincidence that amongst the other casualties was Mahmud, another of the sultan’s sons and in fact his favourite.

None of this would normally trouble historians. After all, premature death was an occupational hazard for any contemporary ruler and parricide a fairly common cause; even when a ruler died in his bed, poison was invariably suspected. The debate over Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq’s untimely demise still rumbles on solely because of the light it supposedly throws on the character of the man who now automatically succeeded to the throne.

This was Muhammad bin Tughluq, the most complex and controversial figure ever to rule India. ‘Muhammad Khuni’ he is sometimes called, ‘Muhammad the Bloody’, Delhi’s own Nero, India’s Ivan the Terrible, the most autocratic, cold-blooded, power-crazed, and catastrophic of sultans who was yet also the most able, cultivated, philanthropic and even endearing. ‘Was he a genius or a lunatic? An idealist or a visionary? A blood-thirsty tyrant or a benevolent king? A heretic or a devout Muslim?’

2

India’s historians being divided by religious as well as ideological allegiances, he remains an enigma. Those of Hindu sympathies find Muhammad’s excesses impossible to forgive and tend to accept Ibn Batuta’s version of his accession. Those of Islamic sympathies favour the Barani version and regard Muhammad as an ill-starred and misunderstood philosopher-king whose gravest error was to antagonise and controvert the Muslim religio-academic establishment, or

ulema.

To this influential class Ibn Batuta belonged. Muhammad would appoint him chief justice of Delhi and then one of his ambassadors. In between, the sultan also disgraced him and gave him cause to fear for

his life. Yet throughout, Ibn Batuta remained fascinated by his master’s personality, unable to decide between reverence and revulsion, seduced by the royal benevolence and appalled by the royal callousness. For Muhammad, he says, was pre-eminent for two things: ‘giving presents and shedding blood’.

At his gate there may always be seen some poor person becoming rich or some living one condemned to death. His generous and brave actions, and his cruel and violent deeds, have obtained notoriety amongst the people. In spite of this, he is the most humble of men, and the one who exhibits the greatest equity.

3

For a tyrant Muhammad’s lifestyle was simple, his libido restrained. Unusually amongst the conscience-ridden sultans he neither succumbed to inebriants nor vigorously proscribed them. He was exceptionally well-educated and of formidable intelligence, outwitting advisers so easily that he soon dispensed with them. He composed verses of outstanding merit; he was an authority on both medicine and mathematics; his penmanship was the envy of Islam’s finest calligraphers; and as a patron of the arts he had no rival until the Great Mughals. ‘But his distinguishing characteristic,’ according to Ibn Batuta, ‘was … a liberality so marvellous that the like has never been reported of any predecessor.’

For this liberality, as for his excessive severity, there would be ample scope although, since the order of events during his reign is uncertain, it is not always easy to trace their logic. The sultan was a relentless campaigner and seems initially to have enjoyed some success in consolidating Muslim rule in areas, like the Deccan, which had previously merely accepted Delhi’s suzerainty. Arguably the sultanate more nearly approached the status of an Indian empire during the early years of his reign than it ever had under the Khaljis. This, however, only encouraged Muhammad to look further afield. A grandiose scheme to reverse Alexander the Great’s march by conquering all Khorasan (including Afghanistan, Iran and what is now Uzbekistan) plus Iraq had to be abandoned in the face of mounting costs. Barani says vast sums were spent on buying up support in these countries and that a cavalry of 370,000 was raised and then maintained for a whole year before the project was dropped.